You have the most fascinating dreams. Unique, vibrant and random, they clearly reveal your artfulness and intelligence—that is, until you try to tell someone about them. Somehow when you get to that part about the bear and your 6th-grade math teacher on the roller coaster, your listener doesn’t find it half as profound as you’re sure it must be.

“To translate a dream in a really striking way, you don’t give a strict interpretation,” explains Michel Gondry, the director known best for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, his Oscar-winning collaboration with screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. “You want to keep some of that abstraction and you want to convey the emotional effect. If you just recount all the details, it’s boring and it just interests you.”

But if there’s anyone whose dreams would be endlessly fascinating in the retelling it would probably be Gondry, who not only visually conjured Kaufman’s heady, sumptuous exploration of love, loss and memory in Eternal Sunshine, but created groundbreaking music videos like Björk’s “Human Behaviour,” the Foo Fighters’ “Everlong” and The White Stripes as LEGOs in “Fell in Love With a Girl.” He’s also the first director to use “morphing” in a music video, and he’s the technical innovator behind filmmaking landmarks like the method of shooting several still cameras in an array to create the illusion of someone hanging frozen in air, as seen in Björk’s “Army of Me” video. (Later this technique was used to stunning effect in The Matrix.)

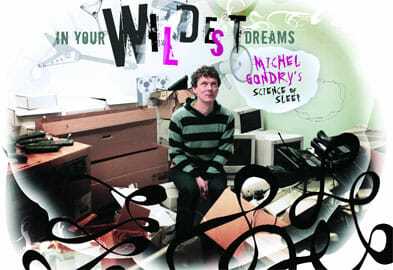

In The Science of Sleep, the first feature he both wrote and directed, Gondry applies this visionary invention to his longtime fascination with dreams, using plenty of his own subconscious adventures in the process. The story follows the days and (more often) nights of Stéphane Miroux (Gael García Bernal), a twentysomething artist who moves to his mother’s native France after his father’s death in Mexico. When he starts work at a dreary job and meets an intriguing neighbor coincidentally named Stéphanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), his dreams begin wreaking havoc on his waking life, and the line between what’s real and what’s a blip in his nocturnal synapses starts to blur just as much for the audience as it does for Stéphane.

To say the dreamscapes here are fantastical is an understatement; Stéphane’s sleeping world involves, for starters: a talk-show set (for “Stéphane TV”) made of cardboard and egg cartons, machines that take insect form, cities paved with LPs, and a rock band consisting of his coworkers dressed in cat costumes. It’s up to us to guess which of these Gondry dreamed up while sleeping, and which he invented on the page.

“I’ve always been interested in the dream process,” he says, explaining that, even as a child, he tried to make real-world connections with people while in a lucid-dream state—for example, saying something to a family member in a dream and hoping they’d repeat it to him when they were both fully awake. “That was the starting point for the story, connecting [with people] in dreams, but not being able to connect in real life.”

Gondry decided to take that need for connection (referred to, by Stéphane, as “Parallel Synchronized Randomness”) and add the possibly budding romance between Stéphane and Stéphanie, both creative but introverted people who have problems enough communicating without Stephane’s increasingly shaky hold on reality. To make things worse, Spanish-speaking Stéphane’s lack of skill in French forces the two to have limited, often bizarre conversations in English—a screenplay quirk Gondry fully intended. “You use a different part of your brain,” when you have to speak with someone in your non-native language, he says. “It can give you some freedom to interact with people and … you might feel less self-conscious about what you’re saying.” On the other hand, he adds, it can also lead to awkward misunderstandings and the feeling—that Stéphane has—of being an outsider.

Gondry, a Frenchman, has experienced this in the U.S., adding a personal touch to the story. But there’s actually little in the film that doesn’t seem personal. Among much else, Stéphane’s apartment is in a building in Paris where Gondry once lived, and the office where Stéphane works is a piece-by-piece reconstruction—down to the wall hangings and typesetting equipment—of an office Gondry worked in more than 20 years ago. These details provided a sense of familiarity for the director as he took on the challenge of both writing and directing a film, something that was frightening, “especially after having directed scripts by Charlie Kaufman,” he says. “It was very scary, but … I guess I’m going to be scared no matter what, so I might as well be scared doing something I haven’t done before.”

Still, he’s thankful to have worked with the “brilliant and original” Kaufman and says it’s helped his own writing. “I cannot compare,” he laughs, “but I try my best.” It turns out Gondry greatly enjoyed being forced to clearly express himself and to “learn to communicate emotions” to the point that his dreams—quite literally—could become reality. At one point after a party during the film’s shooting, he went back to get a bag from the reinvented office set of the place he once worked, and felt amazed by the point he’d reached in his career. “I sat for awhile and looked around, and I thought it was crazy that I had the opportunity to do this—to take a memory and have a crew of people re-create it. I’m quite lucky to have that.”

Surely people who loved Gondry’s work on Eternal Sunshine—not to mention Dave Chapelle’s Block Party or the 2001 film also written by Kaufman, Human Nature—will be thrilled with his first foray into screenwriting. They’ll also get to see film techniques Gondry says he’s been “cooking” in his head for years, like the blast of “spin art” that starts the film, the illusion of flying created by Bernal swimming through a tank of water with projected animation, or Stéphane’s fantastic invention for Stéphanie, the One-Second Time-Travel Machine. And this is just the beginning: this fall, Gondry will start shooting another film he penned (named, as of press time, Be Kind, Rewind), and he has plans for many more projects, including music videos—something he still likes to do.

For the most part, though, writing films hasn’t changed Gondry’s directing style. He still likes to keep it “loose,” leaving room for “some happy accident,” and he still often lets actors make their own decisions. He says that in a restaurant recently, a waiter asked him if he wanted the food he’d just ordered for a first or second course. “I couldn’t make up my mind,” says Gondry, “so I said something and [the waiter] didn’t really hear me, but he left, and I said to the person with me, ‘That’s how I direct people.’ I knew he didn’t understand what I said, but he made his own decision based on that misunderstanding, and I think that’s as good as any decision I could make.” Often if Gondry gives an actor direction, and the actor asks, “Okay, so should I do this?” and it’s the opposite of what was requested, he still says yes. “It’s not really important,” he says. “It’s just a question of moving forward and conveying the right energy.”

He was very happy with the interpretations his Science of Sleep actors achieved. Bernal, not really known for his comic roles, manages to coax big laughs while also being disarmingly sensitive; Alain Chabat, a popular comedian in France, provides comic relief as Stéphane’s raunchy coworker, Guy; and Gainsbourg—a highly respected French actress who has yet to gain a major following in the U.S.—fully “embodies” Stéphanie, Gondry says, bringing the sweet-yet-strong character beautifully to life.

Though Sleep and Eternal Sunshine are multilayered, Gondry says he doesn’t want to make confusing films (he says he can’t stand overly plotted thrillers), he just wants to make films he’d enjoy watching and create stories people can connect with. He says people probably connected to Sunshine because there was something to it (perhaps in the way its lead—Jim Carrey as Joel—appeared weak and rejected) that resonated with them. This is why he loves Charlie Chaplin films; though some people find them “too sentimental,” Gondry says they touch us because they show that even our heroes can be vulnerable. “I feel like [in films] we need to talk about the little shames we have. Then people can relate and say, ‘Oh, maybe I’m not the only one to be … rejected, to not be strong.’”

At the same time, Gondry says, the best films don’t explain everything to the audience. “I like movies that don’t give away all their keys, because I like to look for them,” he says. Like dreams, perhaps they should be a little abstract, a little more open to interpretation. And, like a dream described to someone else, a film’s strength is all in the way the story is told. “It’s all about figuring out how you’re going to make the story happen,” he says. “It’s [finding] the invisible thing that you have to put in while you are telling your story that will make it special.”