What whiskey makes us remember

After 9/11, sages in the publishing world predicted a further decline in novel reading and an increased interest in nonfiction. The real world was too much for us, now, to fool around with fanciful, made-up stories.

Sure enough, among storytelling books, the memoir reigned on high until several of the most successful turned out to be fiction. Or at least fictionalized versions of the truth.

Well, good. Fiction’s probably a better medium for memoir anyway. Twain declared that Tom Sawyer was all true. Wolfe didn’t make much up, did he? My Ántonia is an emotional autobiography of Willa Cather’s youth. Then there’s Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

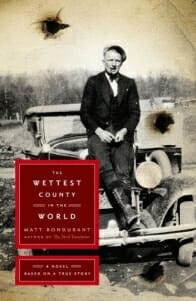

Matt Bondurant’s second novel, The Wettest County in The World, openly and happily sits on the fence between these fields. Subtitled A Novel Based on a True Story, it begins, “The brindled sow stood in the corner, glowering at the boy. Jack Bondurant hefted a bolt-action .22 rifle with a deep blue octagon barrel, the stock chewed and splintered from brush and river stone.” Here you have, right away, the rich, flavorful detail, the authority of deeply involved witness, and the presence of Jack Bondurant, the author’s grandfather, as the main character. And, of course, the direct, unblinking promise of bloody violence.

Bondurant’s grandfather and two grand-uncles ran illegal whiskey—white lightnin’, moonshine (its makers just called it corn or whiskey)—out of Franklin County, Va., in the 1920s, and were known for the brutal enforcement of their independence and protection of their investments. Matt Bondurant recreates, or I should say largely imagines, the circumstances and events that led to a fatal confrontation between the Bondurant brothers and a corrupt local syndicate bent on controlling all the illegal hooch coming out of the county.

In an afterword, Bondurant (The Third Translation, 2005) explains that, starting with family stories and historical record, including the transcript of a well-known trial, he essentially wrote “a parallel history” of these people from his family’s past. He had to invent much of it, and says, “My intention was to reach that truth that lies beyond the poorly recorded and understood world of actualities.”

Jack Bondurant—whom the author knew only as an old, quiet man his family visited a few times each year—comes alive here as an ambitious young fellow determined to escape his apparent fate as a poor tobacco farmer. Jack’s brothers, Howard and Forrest, are complex, violent, taciturn men who, respectively, make and distribute whiskey, bringing Jack into the business when it’s obvious he won’t stay out. The Bondurant brothers are the crime bosses of Franklin County, until the local Commonwealth Attorney decides to horn in with corrupt lawmen as his enforcers. The ensuing conflict is bloody, murderous and inexorable. A cut throat, a castration, a body broken from head to toe, men shot at close range—we can assume that these are not necessarily details Bondurant made up, but he recreates them vividly.

It’s not all grim, though. In one hilarious chapter, “Aunt Winnie” returns home early to find that her house and all its plumbing have been transformed into a still.

One of the book’s more curious elements is Bondurant’s use of Sherwood Anderson, author of the iconic Winesburg, Ohio, as a character. Anderson, who moved to Virginia and bought a couple of local newspapers, provides a pensive outsider’s perspective. In some of Bondurant’s most wonderfully gloomy, lyrical prose, the author-turned-journalist ruminates on the grim economic forces behind such a booming illegal trade. “It was a never-ending battle to make do with what you already had,” he writes, “and when things gave out they literally exploded into red dust.”

But the real heart of the book is Bondurant’s grandfather, Jack, a sensitive young man ill-suited to the violent world of whiskey running, yet determined to escape from a Sisyphean life of back-breaking work with little or no material reward. He won’t maim and murder for his reward, but he’ll help his brothers do that, without apology. Watching a group of embittered old-timers, he thinks, “They only chew on the cud of their past. That’ll never happen to me…. Not to me.”