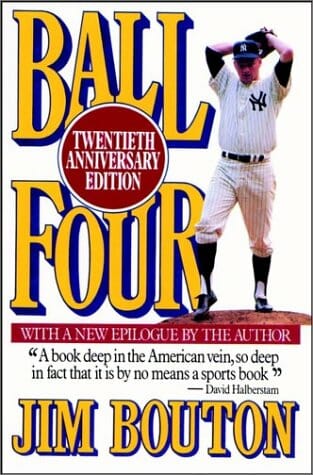

“A book so deep in the American vein, so deep in fact that it is by no means a sports book.” – David Halberstam, on Ball Four

As the 2012 baseball season opens, the time seems right to revisit Ball Four, a chronicle of a season that, for its author, was a time of reflection and hoped-for rebirth—as is the start of any season for athletes and fans. Back in 1969, Jim Bouton wasn’t trying to change the world; he was simply trying to keep a diary of his season.

Once a promising right-hander for the Mantle-era Yankees, Bouton injured his arm during the ’65 season and struggled to regain his status as a starting pitcher. Smart and opinionated (never a combination that many jocks could claim, much to the delight of parsimonious owners), Bouton delivered a book that lifted the lid off the official mythology of athletic glory … and in the process he became much more than a pretty good knuckleballer.

Ball Four hit with the impact of Citizen Kane in cinema and Sgt. Pepper’s in rock music. Sports books existed before Ball Four, and sports books came after. Never, however, has there been anything quite like Bouton’s book.

Praise, of course, comes with a caveat. As Bouton opened the door to the secret world of the boys’ clubhouse, other athletes felt compelled to take the door off its hinges and let all the smoke clear. Bouton acknowledges in the introduction to the edition of the book I have (the 1990 edition, pre-steroid era), that Ball Four unknowingly changed the way that athletes and former athletes themselves wrote sports books. Gone went the days of live right, practice hard, and you can make it. Athletes suddenly felt compelled to top the “revelations” of Bouton’s book simply to sell more copies.

Read today, Ball Four doesn’t seem all that inflammatory. (We now know, thanks to Bouton, that Mickey Mantle chased women and hobbled his career with alcoholism and poor physical conditioning). At the time, however, Ball Four got Bouton hauled in to the commissioner’s office. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn wanted Bouton to retract all that he’d written because it went further than sports books or journalism of the day had ever gone. Reporters of the time generally passed themselves off as pals with sports icons. Kuhn felt it bad business to piss off your sources by revealing their peccadilloes—how many drinks and how many dames they had on the road, for instance.

Bouton became baseball’s Public Enemy No. 1. The Yankees refused to invite him to their annual Old-Timer’s Day for decades. Today? When a player or former player airs material far more salacious than baseball players looking up the skirts of unassuming females, the rewards include round-the-clock interviews on ESPN and maybe a slap on the wrist from a commissioner.

The figure most comparable to Jim Bouton may be Jose Canseco, the former “Bash Brother” to Mark McGwire in Oakland. Canseco today seems most notable for dating Madonna (at least he claims this in his own tell-all book, Juiced) and having a ball bounce off his head in a moment immortalized in countless sports blooper airings on TV. Oh, and he hit 462 career home runs, putting him at number 32 all-time.

All those home runs turn out to be part of Canseco’s problem. Not since Bouton has there been a social pariah quite like Jose Canseco. Juiced broke the code of silence between baseball players and managers regarding the use of anabolic steroids. Though Congress later uncovered evidence that backed his allegations, Canseco became the Benedict Arnold (or the new Jim Bouton) of baseball, a rogue who dared to speak of things not spoken.

I’ve never actually sat down and read Canseco’s book, but I do remember the way sports journalists had to balance their outrage at Jose for openly writing about steroid use against the outrage they then personally had to express when it turned out McGwire and Sammy Sosa (the heroes who saved baseball in the summer of 1998 with their home-run chase of Roger Maris’ single-season record) were ‘roid cheats. McGwire and Sosa both appeared before Congress with Canseco; McGwire suffered apparent memory loss and Sosa forgot how to speak English. In time, Barry Bonds, the man who broke both McGwire and Sosa’s tainted records (and eventually Henry Aaron’s lifetime mark), would also be accused of using human-growth hormones, further casting suspicion on the entire game of baseball after 1989.

Bouton, by contrast, wasn’t really in it for the notoriety. He had a family to feed, and salary issues dominate his book. In the era before free agency, a ballplayer found himself at the mercy of his club’s owner, and that mercy often proved terribly lacking. Fifty years removed from the Black Sox scandal (when eight players from the White Sox threw the World Series just to pocket a little more pay than the peanuts paid by the team owner), salaries still weren’t much better. Even the Yankees, dominant since the age of Babe Ruth when it came to the post-season sweepstakes, turned stingy when it came to paying talent. Owners easily pushed most players around and forced them into less-than-favorable signings. Bouton, on the other hand, stood up for himself. His querulous dealings with management, along with his injury, gave New York an excuse to trade him, but the haggling over money that began with his rookie contract put him on management’s bad side wherever he went.

As Dan Epstein’s entertaining book Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ‘70s (Thomas Dunne Books, 2010) points out, baseball fell out of step with the times during the ‘60s, when civil rights and the war in Vietnam were issues best left at the stadium entrance. The counterculture didn’t really start to change the national pastime until Ball Four, which revealed that baseball’s conservative image hid all kinds of social deviancy, ranging from the juvenile (pranks such as the “hot foot” played on rookies by season veterans) to the more serious (serial infidelity, alcohol abuse). Bouton’s book recounts an incident with Elston Howard, the first black player on the Yankees. Bouton and Howard’s wife argued in favor of civil disobedience while Elston opposed it. Though ballplayers popped amphetamines to stay awake during day games after a night out on the town, society still held up ballplayers as role models for the youth of America. Indeed, this is an issue we face today, inflamed by pervasive 24/7 media coverage.

Bouton was no saint himself, but here’s what really turned him into the most hated man in baseball: He told the truth. He gave everyone else the ‘inside baseball,’ telling what the old ballplayers and their chums in the press box already knew.

At first, Bouton’s revelations didn’t square with public belief. Then, when people realized they’d been sold a falsehood, they returned to Bouton’s book for the truth. He became an oracle.

Three years after Ball Four hit book stores, a group of burglars would be caught sifting through the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in a Washington hotel. In a short time, America would learn some harsh truths about the government that they’d entrusted to Richard Nixon and his gang. It would be hyperbolic to argue that Ball Four helped prepare the nation for the Watergate scandal. Still, the book’s revelations clearly prefigured the end of innocence that Nixon’s downfall would engender in the country.

Ultimately, this is where the problem lies with Ball Four, at least compared to its imitators. With the blinders off, the public discovered a bottomless appetite for gossip and locker-room secrets. Many a ballplayer of dubious ability on the playing field found a niche as the author of a book that ensured its sales by trading on confidences or revealing anecdotes about public figures we thought we knew. When those athletes and their ghostwriters failed to deliver trustworthy journalism, sports journalists no longer in thrall with their sources were left to expose the shenanigans. Their tomes turn out to be many a sports fan’s guilty pleasures. A lot of people can make a living writing and debunking sports mythology.

In some ways, Ball Four didn’t go far enough. Read at one level, the book describes Bouton’s heartfelt struggles to master the knuckleball, the most deceivingly simple of all baseball pitches. In order to throw a knuckleball, Bouton had to minimize delivery motion to maximize the effect of the ball as it left his pitching hand. He traded the overpowering speed of the fastball for the slow, unpredictable, deliberate journey of the knuckleball, which (if Bouton were lucky) maddeningly dipped at just the right moment away from the batter’s reach.

Eventually, the Yankees would make peace with Bouton. The team invited him back to Old-Timer’s Day, and he found financial success as a public speaker and co-creator of Big League Chew bubble gum.

But Bouton acknowledges that his legacy, for better or worse, is Ball Four. Today, the book has more than earned the praise that David Halberstam heaped upon it at publication (and quoted on the cover of the edition I have). It truly is “…more than just a sports book.”

Jim Bouton didn’t set out to change the world, but oftentimes people who change it aim first at something else entirely. Ball Four threw the sports world a knuckleball. The repercussions can still be felt.

Trevor Seigler earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Clemson University in 2008, and has written for various humor and pop-culture websites for more than a decade. Feel free to send him a friend request on Facebook or follow his blog, Arcade Fire Can Save Your Life, at http://arcadefirecansaveyourlife.blogspot.com/.