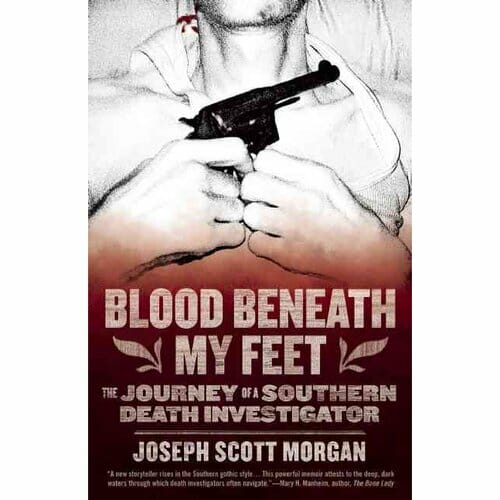

Blood Beneath My Feet: The Journey of a Southern Death Investigator by Joseph Scott Morgan

Death becomes him

Books Reviews Joseph

Even Joseph Scott Morgan’s moniker seems like ominous, narrative foreshadowing. He was named for a homicide victim.

His beloved great uncle, Joseph, was gunned down in a Louisiana street over a painters’ union dispute, and his slayer was pardoned by Governor Earl Long. For the next 20 years, on the anniversary of the event, the family, seething with grief, sent the freed killer a black wreath with a ribbon inscribed in gold script: “We Will Not Forget.”

“From the moment I was old enough to listen, I was regaled with stories of a man I never met but for whom I bore a name,” writes Morgan. “Tales of how cruel and unjust his death was, how his killer did not receive justice but that in God’s time he would. My birthright was death.”

Morgan has parlayed that inheritance, with its rococo Dixie dolor, into a legacy of hard-won wisdom and empathy in his book Blood Beneath My Feet.

At 21, he started sweeping the floors in a morgue in New Orleans’ Jefferson Parish. When he assisted with his first autopsy, his stomach proved as unflinching as his curiosity. In the late 1980s, he became one of the country’s youngest medicolegal death investigators, logging 7,000 autopsies and 3,000 next-of-kin notifications around New Orleans, then Atlanta.

Along the way, Morgan acquired the crisis responder’s seen-it-all catalogue of anecdotes about putrefaction, the industriousness of maggots, and sundry, bizarre methodologies for ending a life, stories he learned to temper at the dinner table and otherwise relate with fine-edged gallows humor. He found satisfaction in the intensity and singularity of the work—“there are more fighter pilots and brain surgeons than death investigators”—at least until, about 20 years into the job, he found himself at the scene of a traffic accident, clinging to another man’s charred, detached arm under a dark, wet Atlanta overpass and trembling so violently he could not stop. A psychiatrist pronounced Morgan the worst case of post-traumatic stress disorder she had seen since treating soldiers who were just returning from Vietnam. After so many years of tensile stoicism in the charnel house, it was time for him to quit.

I met him not long after this imposed early retirement, when a stark ad in the local newspaper piqued my curiosity: “Lunch with Death,” it announced, in what sounded like an odd, Bergmanesque direction for a nearby college’s continuing education program in north Georgia. During this seminar, Morgan’s eyes looked sadder than a caged basset hound’s, but he wisecracked and deadpanned his way through a harrowing slide-show and memory reel that quickly dispensed with everyone’s appetite (just hearing the word “fluid” still raises my gorge), though, like rubberneckers, none of us could turn away.

As a speaker, Morgan ranks among the best of those luxuriantly expressive, meandering storytellers, by turns as blunt as the tissue-smeared sledgehammer used in so many of those crime scenes, or flowery enough to require a trellis for all of that adjectival wisteria. He is a music lover, and it shows in his gallivanting cadences. Talking about his experiences unburdened his mind, which roiled with “images I’d have to slaughter a hog to get rid of,” he says.

Writing would prove even more cathartic. Luckily for readers, his darkling, nightshade drawl translates to the page with just enough pickling salts to keep it from cloying; his debut might help revivify the moribund tradition of Southern Gothic. In fact, it is easy to imagine Morgan making a cameo appearance in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” Blood Beneath My Feet—a sanguinary, though not at all sanguine work—clearly functions as a “therapeutic memoir,” or, in the words of author Grant Jerkins, “a new genre—nonfiction noir. Let’s call it a memnoir.” With it, Morgan has pumped the old “open a vein and start writing” axiom into a torrential burst of aortic hemorrhaging; instead of the usual razor, he used the Grim Reaper’s own scythe on himself.

Gore-hounds, like those maggots, will find much to feast upon in these recollections. Morgan has lit a Marlboro from the ignited gas of a dead man’s bloated belly; he has cradled an intact fetus, with umbilical cord still attached, plucked from the sewage of Atlanta; and he has seen decomposition fluid dripping foully from an upstairs apartment directly into a pot of red beans and rice simmering below (he and his colleagues gallantly bought dinner for the unsuspecting cook’s family and discreetly replaced her cookware).

When the Jefferson Parish morgue, situated atop an old gallows, had run out of space for 16 barge workers killed in a hurricane, Piggly Wiggly provided a refrigerated truck, where Morgan bunkered down for days to catalog and identify bodies battered by the Gulf and ravaged by marine life. Long after that assignment, he shaved all of his prized facial, head and body hair, and painstakingly plucked his nostrils to remove the lingering stench. A co-worker had performed a “professional courtesy among death investigators” by perfunctorily sniffing him and declaring: “You stink.” So heavy on the olfactory senses are some of these descriptions that a reader will welcome a whiff of formaldehyde like French perfume.

The codas to death-scene investigations and autopsies anguished him in a different way: His duties also entailed notifying a victim’s family. He writes movingly about an early case, when he was still in his 20s and eager to demonstrate his clinical acumen and detached professionalism. He informed a rural woman by phone that her son had died of “autoerotic asphyxiation.” She asked for a definition of those cumbersome words and he explained, “with brutal simplicity,” that her son had been found dressed in women’s garments with a bag over his head, and that he had died while masturbating. “I had robbed a woman with my words,” he writes, “and like the clang of an old church bell, thoughtless words could never be recaptured.”

As I read that guilt-stricken recollection, I flashed back to Morgan’s “Lunch with Death” seminar when he recounted the clinical details of a particular case and summed up the victim’s colorful demise with “this gentleman went to Jesus.” It struck me then as a peculiar and courtly euphemism for such a world-weary, no-bull death investigator. Now it made sense.

In that vein, all of this book’s unsentimental shop talk transcends slasher-flick sensationalism because Morgan juxtaposes it with swells of feeling and sensitivity in scenes of personal autobiography, including his fractured, trailer-park upbringing. (This evokes shades of Harry Crews with its Saturday night/Sunday morning dialectics of “mean-ass drunks” and old-time religion, set against a thumping backbeat of Jerry Lee Lewis and Nawlin’s R&B.)

If you wonder how Morgan survived his job as long as he did, well, read about his childhood.

In 1969, he was playing in a sandbox near his grandparents’ chinaberry tree when his father roared after him with a “bellyful of Wild Turkey and a sawed-off Iver Johnson double-barreled shotgun.” His grandmother scooped little Joseph up, stashed him under the bed, and began to pray while the attacker outside howled, raged, and hurled lawn furniture at their rickety shelter.

“There were days as a death investigator when I would think, ‘I didn’t sign up for this,’” Morgan writes. “And who would? You’d have to be crazy not to question your sanity if, of your own free will, you chose to deal with dead children. The pros tell you to dismiss it, to block it out. You toughen, you harden, you disengage, you forget, you move on, you wake up, and you’ve lost your soul. For a load of reasons, one of which was my father, I arrived at my job already an expert at some of those skills.”

The most affecting passage of Blood Beneath My Feet occurs when Morgan recounts a case on Atlanta’s south side. A woman, out of her mind on crack, had grabbed her crying, colicky baby by his ankles, swung him over her head “like a medieval mace,” and slammed him against a bedpost. When Morgan arrived on the scene, she was laughing uncontrollably, and he experienced an awful epiphany: “There are not that many degrees of separation between myself, when I was a child, and this dead baby. My early life was defined by the crashing rhythms of Jerry Lee and a whiskey-soaked father on his slow path to Hell; this little being’s crack-addicted mother had chosen a glass pipe and ‘the Bankhead Bounce’ over him. And, in the end, both our fates had been sealed by a bed. It’s just that one bed had been able to ensure my future and the other bed had destroyed his. The terrified little boy I was had become a man who witnessed death daily, and still I wish all of us could fit under my granny’s old mattress, holding each other tightly against the sound of the sirens.”

Like his forebears grieving his great-uncle every year with a black wreath, Morgan will not forget these events. Neither will anyone who reads his story, and wishes for him a vital, carefree and joyful old age.

Candice Dyer is a freelance writer based in the mountains of north Georgia. Her work has appeared in Men’s Journal, Garden & Gun, Correctional News, Georgia Music Magazine, and Atlanta magazine. Her book Street Singers, Soul Shakers, and Rebels with a Cause: The Music of Macon was published by Indigo Press.