The parallels between Gravity and All Is Lost are obvious: A lone protagonist survives the destruction of her or his space shuttle/boat, loses all communication with Earth/land and must navigate solo through the vastness of space/the ocean to get back home. But in some ways, writer-director J.C. Chandor’s story about an old man and the sea is a bolder film, eschewing backstory, sentimentality and even dialogue in favor of a primal tale of survival.

Robert Redford, credited only as “Our Man,” speaks just a handful of times in the movie, the first a voiceover in which he’s penning a letter. “I’m sorry,” he writes. “I tried…goodbye.” In Gravity, a dead daughter gives Sandra Bullock’s character the will to live. Here, we don’t know to whom the message is addressed, and it lacks personal details that would tell us anything about him other than that he probably does love someone, somewhere. He wears a silver and turquoise ring on his left hand. Is he married? He also bears leather and string bracelets on his wrists. Gifts from his grandchildren? We’ll never know. And we don’t need to, for the human drive to survive is what fuels this story of resilience and perseverance.

After this brief foreshadow, the script kicks back to eight days earlier when, sailing solo 1,700 nautical miles from the Sumatra Straits in the Indian Ocean, Our Man is woken by a crash and the rush of water flooding his cabin. His yacht has struck a Chinese shipping container full of shoes, leaving a gash in the side of the Virginia Jean. Diligently and methodically, he goes about dislodging his boat, mending the breach and salvaging his equipment. But without his electronics to communicate or navigate, he sails right into the path of a violent storm. The obstacles to his survival—some pure chance, some human error—pile on.

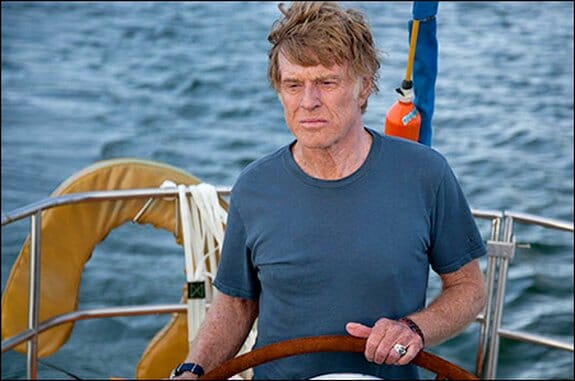

In a physical role that exemplifies the fragility of life in the face of Mother Nature, the fit, capable yet nonetheless 77-year-old Redford hoists himself up the mast, gets tossed around the cabin as the boat roils in the water and is swept overboard. He also demonstrates remarkable ingenuity—the camera content to sit with him while he thinks, his face lighting up when he sparks on an idea—and dignity, pausing to shave before he abandons ship. And practicality: He risks life and limb to return to his sinking vessel for a sextant, not personal mementos.

When Our Man does speak again, he cries out from frustration and, briefly, resignation—not Sandra Bullock’s desperate pleas to God. Saving his voice for the nadir of his experience renders it all the more powerful. If he prays, he does so to himself.

Sans dialogue, the sounds of the ocean and the Virginia Jean become the soundtrack of the film: water lapping, ropes creaking, thunder rumbling, sails snapping, wind whistling, metal groaning, waves crashing. Alex Ebert’s score—by turns droning and thumping—flows underneath, buttressing rather than overpowering the natural soundscape.

Meanwhile, cinematographers Frank G. DeMarco and Peter Zuccarini (for the underwater scenes) capture nature’s stunning visuals: a peaceful sunset, a refreshing rain shower, the raw beauty of sea life swimming just below the surface. Such images remind us that even in the midst of tragedy when Our Man is working merely to survive, there are moments of grace—not all is lost.

Director: J.C. Chandor

Writer: J.C. Chandor

Starring: Robert Redford

Release date: Oct. 18, 2013