Well, there was Three Cups of Tea and what a debacle that turned out to be.

Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin’s 2007 account of how nurse-cum-mountain climber Mortenson became a humanitarian committed to improving the lot of girls in Pakistan and Afghanistan clung to the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list for four years—until author Jon Krakauer (Into the Wild, Into Thin Air) called foul, claiming the authors made up some of the book’s most significant episodes.

Gasp!

Mortenson turned out to be not such a daredevil risk taker after all, shocked readers and fans learned. He never suffered as the victim of a crazy kidnapping (a key incident in Three Cups) in an insane land. Krakauer revealed him to be merely a first-rate storyteller, and for that Mortenson had to pay a steep price, which included the boot from a charity he’d set up to fund schools in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

This story leads to a larger point: From America’s living rooms, how do we tell where to draw the line between fact and fiction in such a distant, volatile corner of the world?

The U.S.’s 12-year involvement in the region makes Afghanistan a more or less constant presence in our lives, yet how much do we really know of the place, its people? Many of us can rattle off in-the-news names like Kabul, Kandahar, Peshawar and Mazar-i-Sharif. We know the terrors of the Taliban then and now—who hasn’t heard of Malala Yousafzai, the brave Pakistani school girl who took a Taliban bullet to her head? We’ve read about the Afghan warlords, and even today, when the focus of the U.S. has shifted to other battlefields (Syria, Libya), news still comes from Afghanistan peppered with stories of hostage takings, kidnappings (hey, supposedly Mortenson made his up, but they happen), and even beheadings.

It’s fact. These things happen. We risk exhaustion reading of such violence. And yet stories about Afghanistan continue to attract readers—not, I believe, because they remind us in our cushy lives of the daily terror and repression that many people (women in particular) elsewhere face. We pay attention because these stories bring us something more human, deeper than headlines.

Look at feel-good, non-fiction books like Kabul Beauty School: An American Woman Goes Behind the Veil, by Deborah Rodriguez. Or Norwegian journalist Asne Seierstad’s The Bookseller of Kabul. Such books give us insight into the day-to-day lives of ordinary Afghanis, and help us grasp why we bother to be involved in such a place.

Fiction tells the truth too. Algerian writer Yasmina Khadra’s 2005 book, The Swallows of Kabul, tells the story of two couples whose lives become enmeshed when the Taliban comes to power. Pakistani writer Nadeem Aslam’s 2009 masterpiece, A Wasted Vigil, depicts Afghans, Russians and Americans dealing with horrific brutality, yet managing to find connections to one another.

Still, given all that’s happened in Afghanistan in the past 12 years, the list of fictional works on that country turns out to be slim. I did a quick Google search and came up with a list of just a dozen titles that span several decades of Afghan history. (These include Ken Follett’s Lie down the Lions; CIA veteran Mitt Bearden’s Black Tulip: A Novel of War in Afghanistan; and James A. Michener’s 1963 opus, Caravans—a book that Jennifer Bryson, Visiting Research Professor in the Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute at the U.S. Army War College, cites as recommended reading for anyone looking to get closer to Afghanis and Afghanistan through fiction.

Snide readers may dismiss these novels as exotic exaggerations, pandering to and furthering the notion of Afghanistan as an inscrutably wild place—one that will slip even further beyond our grasp when U.S. troops exit the country at the end of 2014. But, Bryson insists, these novels help us understand Afghanis.

“A briefing book can tell us how women are treated in a particular region, or that some particular behavior will bring shame to a family,” she writes. “But it won’t tell us what an ashamed man is worried about, or what a woman’s power in a clan feels like.”

To fully understand the people in Afghanistan then—and given our nation’s long involvement there, many of us have more than just a desire to—we must understand their stories.

Enter the raconteur par excellence of the Afghan story: Khaled Hosseini. He authored the bestselling 2003 The Kite Runner, a book that bridged the gap between literary and popular fiction. Simple and beautifully styled, the novel tugged at the deepest heartstrings of many Americans with no prior sense of Afghanistan as a place or culture.

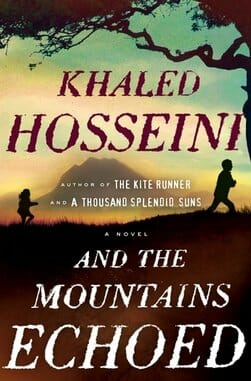

Nobody does it quite like Hosseini…his voice feels so distinct that one thinks of Brand Hosseini. That brand may seem particularly on display in the Afghan-born writer’s new novel, And the Mountains Echoed. At first glance, the work might seem styled to quickly become a Hollywood…or even a Bollywood…movie.

The grandiose 300-page family saga gives us siblings separated by circumstance, then growing up in different conditions on different continents. The pages teem with all the elements for a great tearjerker for the silver screen: Families ripped apart. Dirt-poor villagers, the odds stacked against them. A devoted-to-the-very-end servant. An Afghan warlord. A ravishing alcoholic Afghan émigré (who writes poetry, to boot). Throw in a few French existentialists and a closeted gay man and start the cameras rolling.

Hosseini draws up these characters in rural and urban Afghanistan, but also in Paris, on a Greek island, and off in sunny California. This geo-jumping smacks faintly of Danielle Steele, not least because Hosseini so willingly dishes out to audiences what they have grown to expect from him.

Yup, Brand Hosseini.

Gratefully, Hosseini is no Danielle Steele. What saves this new novel also saved his last, 2007’s A Thousand Splendid Suns, and propelled The Kite Runner to lasting success: Hosseini’s elegant, effortlessly read prose.

Although the author tells more than he shows in this novel, his natural, simple sentences and minimalist style tell stories of real people in a distant, yet very real, land. It sparks major emotions and tweaks even the hardest of critical hearts. (I’ll admit feeling a lump in my throat at several points.)

The novel starts with a story—an allegory, actually—about a monster that steals children from destitute villagers.

A stolen child, the legend goes, will grow up with every imaginable luxury and privilege and will never again want for anything. In exchange, though, the child loses something very valuable: The memory of its birth family.

That family, on the other hand, will be cursed, forever pining for its missing member.

Abdullah will pine in such a way for his sister, Pari, sold by her father to the wealthy, selfish, and spoiled Nila Wahdati (the alcoholic Afghan beauty) to fill her vacant, rather meaningless life. The devoted servant Nabi, Pari’s uncle and the Wahdati family driver, brokers the deal. We learn a secret love for Nila drives the driver’s act: Despite the fact that his love goes unrequited, he feels compelled to fill a void in Nila’s life by giving her his niece.

Abdullah and Pari will experience starkly different lives outside Afghanistan as that country goes through its difficult history. One sibling ends up running a kebab house in California. The other grows up surrounded by a coterie of Parisian intellectuals.

Brother and sister will only meet years later, when Abdullah has become an old, sick man who can no longer even recognize the person he’s yearned for his whole life. Pari can barely start coming to terms with the fact that a crumbling geriatric with a tricky memory really is her brother.

This story moves from Afghanistan in the late 1940s to its post-Taliban/post-US intervention state. Guilt makes plot. Nabi, the old driver (still alive), tries with the help of a Greek doctor working in the war-ravaged land to put back together the family he severed so long ago.

In now-familiar Hosseini style, the reader learns every character’s story…the one major problem with this book. Things go just a bit off kilter with the exposition. A couple of stories seem completely unnecessary to the plot, and these drag this novel out farther afield than needed.

Take the Greek doctor (please!). Even a hardcore Hosseini fan may be forced to admit neither needing nor wanting his story. (I certainly didn’t.)

One other episode follows a couple of minor characters to no clear ending. It sticks out of the novel as painfully and awkwardly as a sore thumb—possibly only to let Hosseini get around to writing a horrific scene of a young Afghani girl whose uncle hacks her skull open with an axe.

Hosseini—a medical doctor by training—was born in Afghanistan, and raised in Paris and later the U.S. (His family received political asylum here when the Soviets invaded their country in 1980.) The author does love to show in his novels the brutality and craziness of present-day rural Afghanistan. He excels in showing the ingenious and inglorious ways people of Afghanistan deal with the realities of their circumstances. His writing always shines with a genuine love for the country of his birth.

A shame, then, that as a U.S. exit from Afghanistan draws closer and a new page of history waits to turn, we get mere glimpses in this book of the great empathy Hosseini holds for that land and its people.

All the more reason, then, to read books like Pakistani writer Nadeem Aslam’s latest, The Blind Man’s Garden, a book that deals at a deeper level than this one with the emotional side of a brutal war and a tenuous peace.

And all the more reason to hope Brand Hosseini will serve up another book soon, this time with a little less Bollywood in the background.

Savita Iyer-Ahrestani is a freelance writer based in State College, Pennsylvania. Her articles and essays have appeared in CNN.com, Vogue (Mumbai, India edition), Mint (India’s largest business daily) Business Week, Vegetarian News, and Spirituality & Health magazine. She co-authored “Brandstorm: Surviving and Thriving in the New Consumer-Led Marketplace” (Palgrave Macmillan 2012) and is currently working on a novel.