The trial, convictions and subsequent quasi-voiding of the guilty verdicts of West Memphis, Ark., teenagers Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley in the 1993 killings of three other, younger adolescents have already served as the basis for four high-profile documentaries, so director Atom Egoyan’s Devil’s Knot arrives somewhat anticlimactically for those who have been gripped by the lurid true crime tale over the past two decades—a queasy, repackaged hits collection of judicial incompetence and malfeasance heaped on top of human tragedy. For those wholly unfamiliar with the case, meanwhile, it’s no less of a mixed bag. If the film’s narrative muddle is somewhat understandable, given the many unanswered questions surrounding the terribly sad events, neither does its lack of a clear mandate gel into something heady and artistic, like a vivisection of crime’s impact on community.

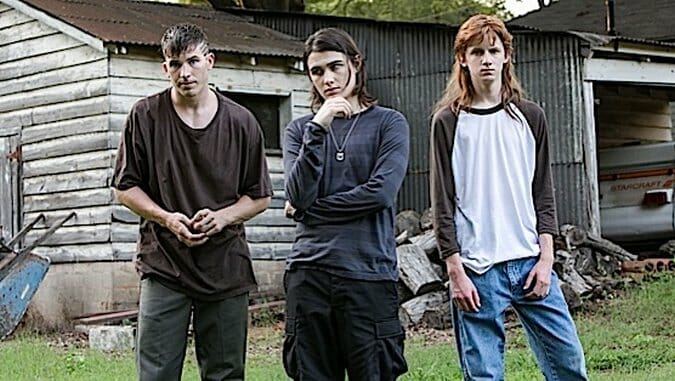

The film unfolds in the aforementioned small town, a deeply conservative burgh with limited socioeconomic opportunity. When a trio of second-graders are discovered dead in a creek, police investigators (in addition to making a litany of very basic errors in the collection and handling of evidence) seem all too eager to believe their murders were part of some occult ritual. Yielding to this “Satanic panic,” they cultivate theories and witnesses to bolster their feelings, much of it centered around suspicion of black-clad outcast Echols (James Hamrick), a troubled high school dropout.

When Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley are charged and facing the death penalty, private investigator Ron Lax (Colin Firth) offers to assist the overworked public defenders representing them. This puts him at odds with not only Pamela (Reese Witherspoon) and Terry Hobbs (Alessandro Nivola), the mother and stepfather of one of the victims, but the prosecutor and entire West Memphis police force.

Adapted by Paul Harris Boardman and Scott Derrickson from Mara Leveritt’s book Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three, Egoyan’s film has the unenviable task of trying to serve many different masters and boil down a thorny, unresolved crime into a cogent narrative. It’s not entirely structured like a traditional procedural, and several unusual moments—as when Pamela takes her dead son’s math homework to his teacher in the middle of a school day, ostensibly to be graded—punch through in interesting, emotional and very human ways. Early on, especially, Egoyan and editor Susan Shipton also intercut between various interrogations to exceptional effect, painting a portrait of a piecemeal investigation governed by impulse.

Unfortunately, once the film settles into its second act, and the trial of Echols and Baldwin (Misskelley, after a recanted confession, is tried separately), the awkwardness of this endeavor becomes more readily apparent. The script shoehorns in some boilerplate outrage via awkwardly expository dialogue (“The state sent over 600 items to the lab, and has nothing that directly links Damien, Jessie and Jason to the murders!”), and dutifully recreates a number of jaw-dropping moments, as when the presiding judge (Bruce Greenwood) grants expert witness status to a mail-order university cult pundit, stating that not everyone in Arkansas needs a college degree to be considered an expert in a field.

But the trial divorces viewers from the broader community. The best portions of Devil’s Knot exist in the most terrible, terrible gray imaginable—a swirling uncertainty regarding the brutal murder of children. But in choosing to track the trial of Echols and Baldwin—admittedly the easiest, most commonplace leaping off point for this salacious case—the movie binds itself to drama of the most desultory, manufactured variety. It doesn’t help, either, that Lax, while a suitably passionate crusading figure, is also something of an adjunct to this tale; he’s not a lawyer, but an assisting investigator, working the case pro bono.

Finally, while he exhibits a keen interest in the story’s social justice elements, the Canadian-born Egoyan also feels like something of a weird cultural fit with the material; he doesn’t get into the bones of Arkansas’ humid, hidden recesses, and fully plumb either its good-old-boy network or rippled tragedies. Anyone familiar with the case is acutely familiar with an almost viral psychological mania that seemed to grip West Memphis in the wake of the killings. Devil’s Knot only scratches the surface of that.

Through it all, Firth and especially Witherspoon (who nicely captures her undereducated character’s accent and smoker’s rasp) deliver focused, engaging work. When the film contrives, however, as part of its denouement, to bring the pair together at the scene of the crime for a sensitive exchange of platitudes as well as evidence that possibly implicates another party, it only reinforces in bold type what the majority of the film has already made clear: this is a serviceable, straightforward work that embraces posed and expeditious dramatic signifiers rather than plunging more daringly into the mouth of madness.

Brent Simon is a regular contributor to Screen Daily, Paste, Playboy, Magill’s Cinema Annual and ShockYa, among many other outlets, as well as a member and former three-term president of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. You can follow him on Twitter and on his blog.

Director: Atom Egoyan

Writers: Paul Harris Boardman, Scott Derrickson, based on a book by Mara Leveritt

Starring: Colin Firth, Reese Witherspoon, James Hamrick, Seth Meriweather, Kristopher Higgins, Alessandro Nivola, Kevin Durand, Dane DeHaan, Bruce Greenwood, Stephen Moyer, Mireille Enos, Elias Koteas, Amy Ryan

Release Date: May 16, 2014