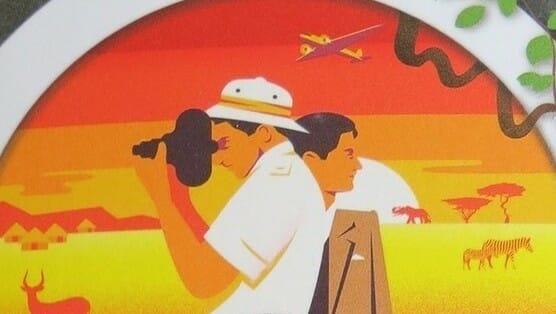

Andrew Lewis Conn’s new novel, O, Africa!, explores the fictional exploits of two Jewish brothers whose commercial partnership propels them to the forefront of the silent film industry in the years between the World Wars.

Conn’s book puts a marvelous spin on a celebrated time when many American Jews’ outsized sense of what it meant to become American—without hyphen or modifier—drove them to outsized achievement.

I doubt that a writer as imaginative as Conn pitched O, Africa! as “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay of the silent film industry,” or anything so derivative. Still, a number of similarities situate O, Africa! in the long shadow cast by Michael Chabon’s 2001 Pulitzer Prize-winner. Fortunately, Conn does plenty to wriggle free of such confining comparisons.

O, Africa! chronicles the fortunes of twin Jewish brothers Micah and Isidor (Izzy) Grand, two halves of a successful silent-era filmmaking team. We meet the Grand brothers in 1927 at both peak and precipice, riding a winning streak of popular (if forgettable) comedies while facing the artistic limitations and limited lifespan of their practiced craft. Synchronized-sound pictures like The Jazz Singer threaten to render them obsolete.

Like Joe Kavalier and Sammy Clay, the Grands offer a study in opposites: Micah is gregarious, arrogant, dissolute and profligate, in it for the women and the fame as much as his love of movies; Izzy is a self-abnegating gay man, emotionally stunted, cripplingly introverted and obsessed with the technical side of filmmaking. The novel spans continents, captures an industry at an explosive historical moment and portrays two talented Jewish men making marketable art and finding a way in. Conn indisputably loves the movies as much as Chabon loves superhero comics, and he sees in them the birth of a nation, the birth of a century and an apt metaphor in the 30-foot screen for all stories rendered bigger than life.

Conn establishes his intentions to trade in era-defining American iconography from O, Africa!’s whizbang opening scene. It features Babe Ruth at a Coney Island location shoot with an impromptu Nathan’s hot dog eating contest pitting Micah against the Babe. It culminates in Izzy’s nerve-jangling Ferris wheel ride with the Grand brothers’ ailing studio head, messily establishing the quieter twin’s persistent state of suspended decisiveness.

Like Chabon, Conn mostly eschews the impulse to chew all this wonderfully iconic last-century scenery, striking a healthy balance between storytelling that’s epic by implication and epic by insistence. The trick with such a book is to suggest how much the story means in the fictional world it inhabits without ever stating it outright—letting legend subsume real life.

Conn appears committed, at the outset, to such a measured approach to large-canvas storytelling, but he doesn’t hew to it consistently. He often indulges in mythmaking at moments that seem undisciplined, but may simply indicate that he’s rack-focusing into a more irreverent narrative mode, or resisting imposed expectations of narrative modesty. Conn’s one previous novel, P., self-consciously (and on virtually every shape-shifting structural level) styles itself a Ulysses of the mid-90s New York porn-film industry. One might reasonably expect Conn to play faster and looser with subject and storytelling modes than the Chabon of Kavalier & Clay.

That said, Conn frequently succumbs to Sister Carrie-esque flights of portentous, over-the-top exposition when he tries to situate O, Africa! in the historical moment and connect it to broader themes. Those slips come at a cost. Take, for example, an episode early in the book where Conn describes Micah Grand’s contentious relationship with his physician father:

Yet here in the figure of his son Micah, with his ease and fluency, was an exemplar of the adopted nation’s addiction to speed, surface, and sensation. The usual patrimonial competition was heightened for having as its backdrop a new country with shifting modes that challenged a father’s mastery.

Conn writes beautifully enough, but the didactic tone oversells the point. The father-son dynamic recalls James T. Farrell’s brilliant story “The Oratory Contest” (1935), in which Farrell documents—with more restraint, and much greater impact—the moment when his own educated, fast-assimilating, post-immigrant generation left the previous one behind. In Farrell’s story, teenage Gerry O’Dell delivers a prize-winning speech, and then dashes his father George’s dream of sharing his son’s triumph by leaving the auditorium unannounced to celebrate with his friends. Farrell separates Irish-extraction past from American future in a single sentence of plainspoken heartbreak: “George asked himself why Gerry hadn’t waited, and he knew the answer to the question.”

Conn’s description of how D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation hooked the then-teenage Grand brothers on moviemaking identifies their fundamental differences much more succinctly than his portrayal of father-son schism: Micah remarks, “It’s magic.” Izzy counters, “No it’s not. I think I have some sense of how he did it.”

O, Africa! picks up steam when the Grand brothers set sail for Africa with a small crew and a wonderfully complex (and secret) filming agenda, including a by-the-numbers silent comedy, a promised landscape-and-wildlife B-roll project and a “black exploitation” film (as characterized by Izzy 40 years too soon). The production means to pay off Micah’s gambling debts. Conn introduces a wonderful technique of beginning a chapter in past tense and switching to present tense as the characters swing into action. The effect works much like a filmmaker lending intimacy to a scene by cutting from a wide shot to a close-up.

Filmmaking assumes another metaphoric dimension in Africa as the brothers focus cameras on Malwiki villagers who comprehend neither the impact of a captured image on the subjects captured nor the purpose of directed play-acting. At first, the book takes a Henderson the Rain King-like turn, as American interlopers blunder into a world they don’t understand and blithely steamroll. (To be fair, Micah Grand brings much more self-awareness to the culture clash than the cluelessly frog-bombing Eugene Henderson). When the story explodes with violence and reckless intrusions beget inevitable tragic consequences, O, Africa! roars into can’t-put-it-down country with real power and grace and rarely relinquishes its grip until it concludes.

Conn does break the flow with an intermission of sorts, in which he gives away the Grands’ future (and shores up their backstory) with two fictional film-reference-book entries chock full of humorous titles, historical context and unabashed myth-making. We get a few oddball allusions here, such as a Grand-produced silent film titled Crazy Chester Followed Me!, borrowed from a line in the Band’s 1968 debut single, “The Weight.” Conn makes an unconventional choice by dropping this digression (which would more predictably function as preface or coda) in the middle of the book, but it serves his purpose better than locating it elsewhere. What’s more, the offhand humor of the Film Companion entries bespeaks an author having fun with his book—perhaps enough to cast his penchant for distracting verbal slapstick like “He was a burgher… a burgher king” and “Where’s Waldo?” in a more forgiving light.

O, Africa! takes on some pretty weighty topics—the unequal perils and challenges of passing and assimilation for outsiders Jewish, black or gay; the power, the language, the limits, and the various metaphoric connotations of fabrication and film; the pleasures and devastations of doomed, socially unsanctioned sex and love; and the consequences of recognizing the insubstantiality of one’s work … or the insufficiency of one’s efforts in the face of relatively easy success.

Conn’s prose proves most dazzling when he cuts loose and couches his belief that all of life’s mysteries can be explained in filmmaking in unabashedly expansive terms:

Watching from this short distance his apprentice’s hands, eyes, and feet working together in concordance with the mechanical apparatus, Izzy marvels anew at how picturemaking combines the technical and artistic, the industrial and the athletic, the modern and the atavistic. How it’s not every day that new modes of experiencing the world come into being.

Therein beats the 24-pumps-per-second heart of this big-hearted book and its vividly realized celluloid heroes. Enthralling, riotous and sometimes frustratingly imperfect, O, Africa! matches the exuberance of its title at nearly every turn, especially as it thunders to a middle and conclusion.

If it sometimes feels—at least stylistically—as if Conn is throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks, make no mistake: it sticks.

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.