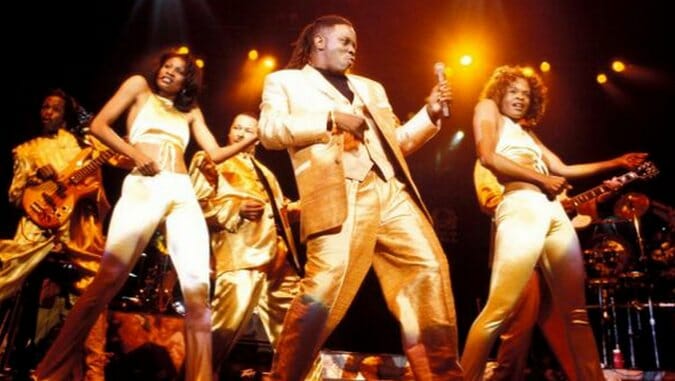

Philip Bailey, singer in the group Earth, Wind & Fire, enjoys a rare privilege for an aging musician. While most members of his cohort look back as current sounds leave them behind, he writes his memoir as pop’s center shifts closer to his past work.

Demand runs high these days for the richly layered arrangements that Earth, Wind & Fire mastered in the mid to late ‘70s. This means Bailey’s new memoir, Shining Star—a history of the group and his role in it—reads as more relevant than your average memoir by a ‘70s star.

Before he hit it big, Bailey married young and lived the hippie lifestyle, complete with an old van that he drove all over his home state (Colorado) to play gigs. His band opened for Maurice White’s first edition of EW&F on a Denver date and made an impression. When White’s initial lineup fell apart, Bailey joined up, bringing his Denver keyboardist, Larry Dunn, along for the ride.

In the new group, Bailey started unleashing his heavenly falsetto. “I loved female vocalists,” he writes, “so I was imitating Dionne Warwick.”

White and Bailey worked closely to craft a unique sound. In particular, they loved Sergio Mendes, feeling “heavily inspired” by vocal interplay “where the melody is sung in a high register with multiple voices, then sung in the lower register with more voices.”

Critically, Earth, Wind & Fire usually gets thrown in with the other big funk groups of the ‘70s, but Bailey has another label in mind. “From a purely stylistic standpoint, Earth, Wind & Fire was a commercial fusion group, as opposed to a funk band like Cameo or the Ohio Players. By musical definition, funk groups weren’t running through the cycle of fourths in a tune,” he says, and they “didn’t use bebop horn licks on top of Afro-Cuban rhythms like we did.”

This commercial fusion group became steadily more successful throughout the ‘70s—hitting it especially big with 1975’s That’s The Way Of The World, 1976’s Spirit and 1977’s All ‘n’ All. These albums each launched number one R&B singles and sold several million copies. Big hits included “Shining Star,” “Can’t Hide Love,” “September” and “After The Love Has Gone.”

Bailey suggests success brought two problems.

The first counteracted their musical fusion. “Ironically, the tighter the studio sound got, the more isolated and separate we became as a group.” The band came up recording live as a unit; now White and other arrangers spliced together various takes from musicians playing in isolated booths.

The second problem? Inequality in pay. Someone usually makes more money than someone else in a band, and this can create resentment in close quarters.

The two issues eventually came to a head, and White dismissed the band. Bailey describes his reaction as “shocked, appalled and crushed with disbelief,” though it should be noted that he already had a solo deal at the time.

The band couldn’t do anything about a third factor working against them—changing times. Bailey “felt utter disdain for disco,” which ruled the late ‘70s. But disco wasn’t the only external impediment to progress.

“[I]n 1980,” Bailey notes, “the entire radio and music industry was in transition.” The big bands that ruled the ‘70s became too expensive. They also began to look old-fashioned, thanks to a combination of market saturation and new technologies (drum machines, samplers, etc.). Solo stars like Michael Jackson and Prince ascended. Lionel Richie even split with his successful band the Commodores to make an even more successful run as a soloist.

Bailey doesn’t spend overlong on his solo career (a smart move on his part), and this reflects a strength of the book—he delivers refreshingly frank assessments of his own artistic output. He’s willing to call Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘80s albums “marginal.” Sometime he may even be too harsh: musing on “After the Love is Gone,” one of the group’s grandest ballads, he notes that “from a strictly technical standpoint, you could make the argument that it is flawed … maybe it should’ve been sung by a female vocalist with a higher and wider gospel range.”

Even so, Bailey sometimes self-contradicts or fails to examine the more difficult aspects of his past. Although he professes to dislike disco, he mentions that Earth, Wind & Fire drew from “the German producer Giorgio Moroder’s immaculate beat-driven hits with Donna Summer.” (And Bailey recorded with disco king Nile Rodgers later in the ‘80s.) The singer also fails to treat his personal life with the same detachment as his music. He quickly shifts blame for his marital infidelity towards his parents, never stopping to acknowledge his own role in succumbing to temptation.

Shining Star carries all the way through the group’s 1987 reunion to the present day, as EW&F rolls on. Though White stopped touring with the group in the mid-90s when he contracted Parkinson’s disease, the band still released albums periodically. In fact, their 2013 release, Now, Then & Forever, sounded remarkably up to date without being forced. Most surprising of all: Bailey can still hit the high notes.

Elias Leight’s writing about books and music has appeared in Paste, The Atlantic, Splice Today and Popmatters. He comes from Northampton, Massachusetts, and he can be found at signothetimesblog.