Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier gets a lot of credit for popularizing the unreliable narrator in modern English literature, but nearly 100 years after its release, the book itself does little to demonstrate why. In Ford’s hands, the approach remains more conceptual than substantial, more incidental than integral. There’s arguably something a bit radical about entrusting a story to a narrator who repeatedly proves himself unequal to the challenge and emphatically undermines his own authority (“Is all this digression or isn’t it digression? Again, I don’t know”). But in The Good Soldier, the trope rarely amounts to much besides demonstrating how craftily such a narrator can be deployed.

Perhaps the most clever use of an unreliable narrator in recent memory occurs in Maile Meloy’s second novel, A Family Daughter. Therein Meloy reveals her entire first novel, Liars and Saints, as the crypto-autobiographical invention of A Family Daughter’s narrator, and she documents all the ways in which Liars and Saints misrepresented the truth and exposed, betrayed and hurt the character’s family. In doing so, Meloy achieves an ingenious twist, a dazzling trick of the light—but not much else.

Ironically, what makes a piece of fiction’s unreliability feel so authentic is that narrators act less like novelists and more like the rest of us. It imposes a veneer of insufficient insight and limited perspective on a fictional world where we expect to be told a story that’s whole in a way real-life stories never are (to paraphrase John Irving). At its best, a story told by an unreliable narrator should feel most right when the teller gets things most wrong.

“Memory—uncorrected, uncorroborated, and (by its very nature) unreliable—is what allows us to retroactively create the blueprints of our lives, because it is often impossible to make sense of our lives when we’re inside them, when the narratives are still unfolding: This can’t be happening. Why is this happening? Why is this happening now? Only by looking backward are we able to answer those questions, only through the assist of memory. And who knows how memory will answer? Who will it blame?”

So muses Emmy Marlow, daughter of Charles Marlow, protagonist of Stephanie Kallos’ enthralling new novel, Language Arts. Emmy appears in Language Arts infrequently, and only as a disembodied voice mostly offering commentary on her father and his foibles. “My father cannot provide a subjective biography of his own life,” she writes. “He has designed his memories, built them into a structure that supports the whole.”

We meet Charles Marlow in the twilight of his long career as an English teacher in a Seattle-area charter high school, at a point at which meaningful points in his past begin to converge with the present. He’s been approached by a reporter to revisit his brief brush with local fame 50 years earlier, when he was interviewed for a Seattle Times article about the city’s first experimental Language Arts class. Meanwhile, his low-functioning autistic son, Cody, is about to turn 21, at which point the state will no longer pay for his care, necessitating some critical co-parenting decision-making. And a talented and driven high school photography student, intent on producing a photo essay at Cody’s current care facility for a senior project, may cause all his present worlds to collide.

Like memory itself, Language Arts skips in time, revisiting moments at which Cody’s illness increasingly asserted itself. In each of these episodes, Charles and his now-ex-wife, Alison, struggled to see eye to eye on what to call Cody’s condition, who or what to blame for it, how much to accept it, how to deal with it and how to deal with him. (Emmy’s comments on her father’s inability to reliably reconstruct his own life make the partisan portrayal of these reconstructed arguments more palatable and relatable.)

Charles also returns, repeatedly, to the pivotal year in his childhood in which he was enrolled in the Language Arts experiment. Through the eyes of fourth-grade Charles we see his apathetic, ill-tempered parents and their boundless contempt for each other. Charles exposes their contentious relationship to the entire community that same year in an award-winning short story that his teacher reads aloud in a magnificently rendered, stunningly revealing scene that may be the finest Kallos has written to date.

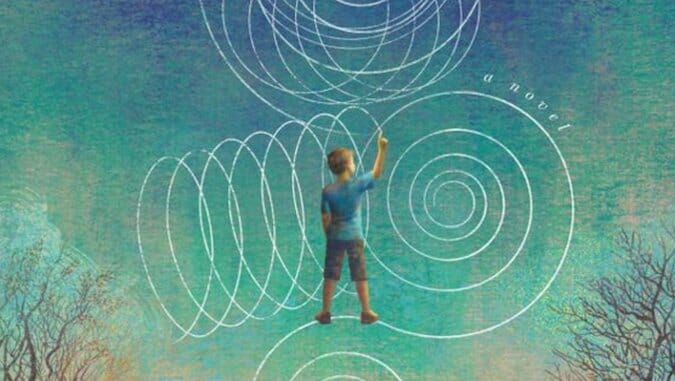

A mentally challenged boy in a white suit named Dana Glucken also steps to the fore in Charles’s momentous fourth-grade year, as the two boys become unlikely friends, due to their general unpopularity and their mutual affinity for drawing pages of repeated “loops,” mandated by the then-fashionable Palmer Method of handwriting as the essential building blocks of skilled penmanship. (Charles himself is a loop-making w?nderkind.)

Charles’s relationship with Dana ends in a tragedy that haunts him throughout his life, to the point that he can never detach himself from it. Against his own better judgment—and with a certainty that he never admits to Alison—he imagines his son Cody’s illness as both a karmic consequence of his role in what happened to Dana and a permanent visitation or occupation. The loops stay with him, too, and the peculiar persistence of the Palmer Method serves as a sort of connective tissue throughout the book, particularly in Emmy’s counter-narrative.

Language Arts revisits two of the themes explored in Kallos’ wonderful previous novels, Broken for You and Sing Them Home: rebirth and redemption found in unlikely human connections, and the challenges of communication across forbidding boundaries, in particular from the dead to the living and vice versa. Kallos populates Language Arts with a host of challenged communicators: Cody, who permanently “lost his words” to autism as a rapidly regressing toddler; Emmy, who speaks only to the reader; Alison, an attorney who communicates in arguments carefully constructed to end discussion rather than encourage it; and Charles, whose linguistic talents lie just outside actual communication in obsessive language scholarship and in penmanship skills that deserted him half a century earlier.

Kallos meets and overcomes her own self-imposed challenges in Language Arts, not least of which is writing a book largely about autism that doesn’t wallow in sentimentality, ossify on the page like a commissioned public service message or veer into sensationalism or science fiction. Kallos’ success in managing risky subject matter (something she’s done in all her books) and rendering such concerns irrelevant stems from her signature gift.

Kallos can spin a reveal like nobody’s business. At her best, she compels you to recalibrate everything you thought you knew about the book, but that’s just Palmer Method loop-making for a writer of her talents. Like most novelists worth their salt, Kallos also knows how to invest a book with enough insight into how humans think to make her characters act convincingly. It’s that extra layer of perceptiveness that separates a good novelist from the rest of our species.

But a feel for a book’s subject isn’t the same thing as feeling for the people who populate its pages, and one thing that separates a good novel from a great one is when empathy accompanies insight. The novels of Stephanie Kallos are filled with the sort of empathy that elevates not just the books but their readers. They convey the overarching sense that repairing the world is a real possibility, however remote—more than one absorbing read away, to be sure, but certainly closer at the last line than the first.