John L. Parker’s Once a Runner, the sine qua non of running fiction, made its debut in 1978 as a book without precedent, peer or publisher. More a legend than a book to some, Once a Runner and its author quickly passed into running lore, as generations of runners recounted the tale of Parker selling self-published copies of the book out of the trunk of his car at road races. Even runners who have never seen the book know something of the story of Quenton Cassidy, a collegiate distance runner who trains doggedly to challenge the world-record-holder in the mile. The chapter titles alone are intimate experiences only competitive distance runners know: “Twenty-four in the Rain,” “More Horse Than Rider,” “Demons,” “The Interval Workout,” “The Orb,” “A Stiller Town.”

Everyone who has lived some part of that experience has probably tried to tell their own take on the story at some point, most likely with more grandiosity and less poetry than Parker’s rendition. In Once a Runner’s lighter moments, Parker captures that too, the way collegiate runners tend to mythologize the rigors of their training to impress girls. And Once a Runner indulges in its own excesses—the tyrannical good ol’ boy football coach and a crusty old dean straight out of central casting. Farther-reaching books have featured running prominently, such as N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn and Alan Sillitoe’s The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner. But no one has ever written about running itself better than John L. Parker, Jr.

Everyone who has lived some part of that experience has probably tried to tell their own take on the story at some point, most likely with more grandiosity and less poetry than Parker’s rendition. In Once a Runner’s lighter moments, Parker captures that too, the way collegiate runners tend to mythologize the rigors of their training to impress girls. And Once a Runner indulges in its own excesses—the tyrannical good ol’ boy football coach and a crusty old dean straight out of central casting. Farther-reaching books have featured running prominently, such as N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn and Alan Sillitoe’s The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner. But no one has ever written about running itself better than John L. Parker, Jr.

At one point in Once a Runner, Parker hints heavily at what he’d set out to do and why it needed doing, as he describes the reading material Cassidy took with him when he dropped out of school and sequestered himself in a cabin in the woods to train:

Soon Cassidy felt he had read everything ever written about running… The novels, while generally flawed technically in one way or another (sometimes tragically so), occasionally captured certain elements of his own striving…Often the day after a late-night reading jag, he took to the country roads and wooded trails with renewed energy, comparing his impressions to his historical and fictional counterparts. He decided that no one had quite captured the strained satisfaction of tooling through the middle miles of a hard fifteen-mile run.

A 4:06 miler and Southeastern Conference champion collegiate runner himself, Parker spent two years in the early-1970s living in a shed by the University of Florida track with Olympic distance runners Frank Shorter and Jack Bacheler, and trained with them twice daily while pursuing his law degree. He knew whereof he wrote, and in Once a Runner he achieved exactly what Cassidy found wanting in the running novels available to him.

Parker described writing Once a Runner as akin to “cutting the top off my head and pouring out everything about running that was in there into this thing and just making sure it wove into the plotline.” If one measure of a good novel is how successfully it collects, distills, and conveys all of the singular and most important things an author knows, and rolls them into a compelling narrative, John L. Parker’s Once a Runner could stand among the most fully realized novels ever written.

Of course, there’s more to novel-writing and publishing than imparting esoteric stuff a writer knows. For whatever reason, in 1978 publishers didn’t bite. So Parker started his own press, and typeset and printed the book himself. Beyond the road-race sales of legend, he peddled the book to running stores, where it was intermittently available by the 1990s, at least in major cities.

In 2007, a Once a Runner sequel called Again to Carthage appeared on a small specialty press called Breakaway Books. Again to Carthage chronicled Cassidy’s return to elite running in his early 30s, and provided fascinating insight into the way endurance athletes experience physical decline more minutely than others to whom aging’s initial onset might be all but imperceptible. In 2009, Simon & Schuster picked up the rights to Once a Runner and Again to Carthage and brought both books out in hardcover.

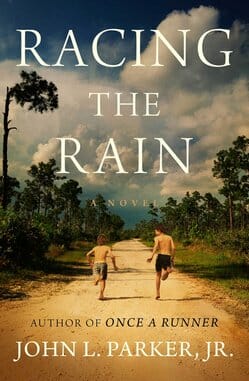

More than 30 years after it became essential reading for competitive runners, Once a Runner was finally, improbably, in print. Now Parker has completed the Quenton Cassidy trilogy with Simon & Schuster/Scribner’s publication of a prequel titled Racing the Rain.

One of Once a Runner’s loveliest chapters, “A Too Early Death,” offered a brief but captivating flashback to Quenton Cassidy’s childhood in coastal Florida. Parker described how a 10-year-old Cassidy “had learned to slip into the sea and plummet like a stone to fifty, sixty feet, there to look around leisurely before floating back, calm and haughty in his control of the pale green waters.” He would use his already-apparent lung capacity to dive deep and hold his breath to frolic among the coral and spear fish, and often to dislodge his father’s fishing boat’s anchor when it got stuck. In the incident described in “A Too Early Death,” Cassidy dives to free a hooked fish trapped in a coral head, hyperventilates, and nearly dies.

Racing the Rain picks up roughly where “A Too Early Death” leaves off, with 11-year-old Cassidy and his friends sharing the barefoot delights of a coastal Florida childhood in the late-1950s—shirts-and-skins basketball, A & W root beer and jerked sodas, mangoes and guavas and loquats right off the trees, swimming, canoeing, spearing fish and racing in the rain.

Racing the Rain follows Cassidy’s adventures through junior high and high school, all the way to his arrival at Dick Doobey Hall as a scholarship athlete at Southeastern University. Much of the intrigue of the book, of course, lies in discovering how Cassidy developed into the elite runner he became, when and how his talent revealed itself, and how he came to recognize his extraordinary ability to focus, train, and endure pain with purpose.

But Racing the Rain offers myriad other delights, not the least of which is the friendship Cassidy strikes up with a (real-life) wild swamp man named Trapper Nelson. Cassidy knows the legend before he meets the man:

Trapper Nelson was supposedly bigger and stronger than Paul Bunyan, had more powers than Superman, knew more about animals than Tarzan; he wrestled alligators for fun, laughed at poisonous snakes. He disliked civilization and lived back in the swamp way up on the Loxahatchee River, hunting and trapping for a living… No one knew more about the ocean, the swamp, or the river than Trapper Nelson.

Initially, Cassidy and Nelson strike up a low-stakes business partnership leveraging 11-year-old Quenton’s underwater fishing talents. Nelson plays a pivotal role in Cassidy’s introduction to competitive running (being the first to make the connection between pre-pubescent Quenton’s exceptional lung capacity and his potential as a long-distance runner), though Cassidy initially shows much more interest in basketball.

As one might expect, Racing the Rain gets cooking when Parker writes about racing, beginning with 12-year-old Cassidy’s first quarter-mile race. Parker’s talents remain without compare in this regard. Like Again to Carthage, Racing the Rain is loaded with elegant and evocative writing, yet never quite matches the ecstatic heights or wrenching pathos of Once a Runner’s finest moments. But both the sequel and prequel are more mature, consistent works. You never feel like Parker is trying to settle old scores, even in the three incidents that presage the anti-establishment impulses and clashes with authority that get Cassidy booted off campus in Once a Runner. Two involve conflicts with stubborn and dim-witted track and basketball coach Bob Bickerstaff. One even leads to an unsanctioned extra-mural race entry that precisely parallels the climactic race in Once a Runner.

The other incident concerns a classroom debate over the real vs. perceived threat of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the implications of nuclear proliferation in fall 1962. Though this comes off as a bit of a soapbox moment for Parker, perhaps a bit too didactic and heavy-handed, it works in the context of Cassidy’s personal development. Even in Once a Runner, largely a story of how exceptional single-mindedness in search of a goal can propel a gifted athlete from the unlikely to the unthinkable, Cassidy always manages to keep one eye on what’s happening outside the college-athletics bubble, particularly the war in Vietnam. The Cuban Missile Crisis debate provides a useful signpost of his evolving political consciousness.

Of course, how much you care about Cassidy’s personal evolution in Racing the Rain depends in large measure on how much you care about Once a Runner. Or whether a sentence like “Quenton Cassidy, unmoved by kittens, sonnets, and sunsets, was nonetheless given to tragic flaws” ever lodged itself in your brain and stuck for no particularly good reason.

Perhaps that’s the way with all prequels, particularly prequels to cult novels. Maybe the question is intrinsic to the anomalous publishing history of Once a Runner, a book about a singular passion that has inspired and electrified a devoted core of readers and elicited total indifference from others. Apparently, it was that indifference that consigned Once a Runner to its place on the margins of the publishing industry for the pre-longtail first three decades of its existence.

In a way, Parker predicted this outcome. For all the cocktail party curiosity he must have encountered in his time as an elite (or once-elite) runner, apparently he rarely, if ever, met anyone who really wanted to know what he knew about running at that level:

What was the secret, they wanted to know; in a thousand different ways they wanted to know The Secret. And not one of them was prepared, truly prepared, to believe that it had not so much to do with chemicals and zippy mental tricks as with that most unprofound and sometimes heartrending process of removing, molecule by molecule, the very tough rubber that comprised the bottom of his training shoes. The Trial of Miles; Miles of Trials. How could they be expected to understand that?

John L. Parker, Jr. has done more to help readers understand that than anyone could have predicted, and never compromised the answer he’s given. In Racing the Rain, he’s delivered a worthy, compelling and satisfying conclusion to the Quenton Cassidy trilogy. We’re lucky to have it.