From the living dead to the walking dead to the typing dead, zombies have completely and utterly suffused 21st century culture. And that’s a pretty weird phenomena, when you think about it.

It’s not like this was always the case. Go back to the ’80s, and to wax poetic about George Romero-esque zombie films would have been the hallmark of a nerdy, acne-ridden high school student in a John Hughes movie. The idea that a TV show like The Walking Dead could be one-upping Sunday Night football in TV ratings? That would seem patently impossible.

Yes, zombies have come a long way, as has our appreciation for them. We live in a society that has become profoundly geekier in the last 15 years, and adopted the once secretive and insular totems of geek culture as its own. But it’s not just us who has evolved, it’s the zombies themselves—the creatures, their films and the people who made them.

Recognizing that evolution, I decided to chart a crude history of zombie cinema by examining the most significant films in the genre from a standpoint of influence. Most of these are considered classics, although some aren’t very widely known. Most are also considered “good films,” but they aren’t necessarily GREAT—they’re just important, for one reason or another. And of course, there’s also a few real pieces of trash on the list because hey—there’s been a lot of terrible zombie movies over the years. So here you go: The 25 most influential zombie films ever made.

White Zombie, 1932

Where else could we begin? White Zombie was the first feature-length “zombie” horror film, and the first popularization of the Hollywood concept of Haitian voodoo zombies, decades before the modern George Romero ghoul. As a public domain staple in just about any cheapo package of zombie films ever assembled, it’s easy to view White Zombie today—you can simply breeze through its 67-minute runtime on YouTube, if you want. Bela Lugosi, only a year removed from Dracula and reveling in his celebrity as one of Universal’s go-to horror performers, plays a witch doctor who is literally named “Murder,” because the studio was still a few years away from discovering subtlety at this point. The Svengali-like Lugosi ends up using his various potions and powders to zombify a young woman who is engaged to be married, attempting to bend her to the will of a cruel plantation owner, and … well, it’s pretty dry, wooden stuff. Lugosi, predictably, is the one bright spot, but you had to start somewhere. After White Zombie, voodoo zombie flicks popped up occasionally in Hollywood for years, most of which are currently in the public domain today. And of course, the film also inspired a certain musical project from Rob Zombie.

I Walked With a Zombie, 1943

I Walked With a Zombie is the second film overseen at RKO by producer Val Lawton, who produced a memorable run of low-budget but artful horror flicks in the early ’40s that included the likes of Cat People and The Ghost Ship. Far more atmospheric and less hokey than White Zombie, this film is a good example in general of the Hollywood system’s refinement from the early ’30s to early ’40s, even with its low budget. The story revolves around a young nurse who travels to the Caribbean to care for a patient who may or may not be affected by zombism, which draws her into a mystery surrounding a local voodoo cult. The cult’s zombie enforcer, Carre-Four, seen in the above photo, is one of the most iconic early images of a voodoo zombie, rocking the cliche “monster carry” pose of an unconscious woman. If only he was actually in the film more, it might be considered as a real classic today, but it’s still about as good as the voodoo zombie films of this time period get. There are some really spectacular individual shots in this film that chillingly play with intense shadows and the towering Carre-Four’s gaunt frame.

The Plague of the Zombies, 1966

Revivals of the classic Universal monsters (Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy) were the main forte of Hammer Horror, but the British studio also managed to produce one great, influential zombie movie that has flown pretty much under the radar in the decades since its release. Plague of the Zombies does feature voodoo zombies, but they’re not quite the same as those early B&W examples. Decayed-looking and truly frightful, with a fantastic design aesthetic, they feel like a true bridge to the Romero ghoul, and the visual influence on Night of the Living Dead is pretty obvious. Featuring great production design and a spooky story about a town slowly dying to a plague of zombism, it’s my personal favorite pre-Romero zombie film, and one that deserves a significantly larger audience. With its glorious Technicolor imagery, it fits in comfortably alongside the better-known Hammer classics from Terence Fisher. You can also include visually similar films such as Vincent Price’s The Last Man on Earth as Romero-influencers, but the creatures in that film are much closer to vampires than they are zombies.

Night of the Living Dead, 1968

What more can be said of Night of the Living Dead? It’s pretty obviously the most important zombie film ever made, and hugely influential as an independent film as well. George Romero’s cheap but momentous movie was a quantum leap forward in what the word “zombie” meant in pop culture, despite the fact that the word “zombie” is never actually uttered in it. More importantly, it established all of the genre rules: Zombies are reanimated corpses. Zombies are compelled to eat the flesh of the living. Zombies are unthinking, tireless and impervious to injury. The only way to kill a zombie is to destroy the brain. Those rules essentially categorize every single zombie movie from here on out—either the film features “Romero-style zombies,” or it tweaks with the formula and is ultimately noted for how it differs from the Romero expectation. It’s essentially the horror equivalent of what Tolkien did for the idea of high fantasy “races.” After The Lord of the Rings, it became nearly impossible to write contrarian concepts of what elves, dwarves or orcs might be like. Romero’s impact on zombies is of that exact same caliber. There hasn’t been a zombie movie made in the last 47 years that hasn’t been influenced by it in some way. Oh, and by the way—NOTLD is public domain, so don’t get tricked into buying it on a cheap DVD.

Shock Waves, 1977

Despite the influence of NOTLD, the film took some time to gestate in the cultural consciousness before a huge wave of significant zombie movies bloomed in the late ’70s and especially the ’80s. Arriving shortly before Dawn of the Dead exponentially raised the popularity of zombies as horror antagonists, Shock Waves might very well be the first of all the “Nazi zombie” flicks. It’s honestly a dreary, slow-paced film, following a group of lost boaters who end up on a mysterious island where a sunken SS submarine has jettisoned its crew of zombies, a Nazi experiment. Hammer Horror icon Peter Cushing appears as a badly miscast and addled-looking SS Commander, the same year he was sneering at Princess Leia in Star Wars: A New Hope. There have been, by my amateur count, at least 16 Nazi zombie movies since this point—certainly more than one might realize—which makes this one fairly significant at least for combining the portmanteau of great film villains first. Films like the Dead Snow series ultimately owe it all to Shock Waves.

Dawn of the Dead, 1978

Where Night of the Living Dead is rough, fuzzy and decidedly cheap-looking, Dawn of the Dead makes a giant leap forward in terms of presentation, professionalism, thematic complexity and groundbreaking special effects. It took Romero 10 years to get his first sequel off the ground, but he ups the ante in every way possible. The plot is more engaging and smartly satirical, with anti-consumerism themes that become apparent as a crew of survivors hole up in a tacky mall overrun by the walking dead. Special effects wizard Tom Savini turns in his first really great adventure in gory experimentation, raising the bar for everyone else who ever wanted to explode a zombie head on screen in the years to come. Dawn is often cited as the all-time greatest zombie film via lists, which may or may not be true, but it’s definitely near the top in terms of iconic status. The violence is rather gleeful, but the sobering reality of the collapse of civilization contains a nihilistic streak common to zombie apocalypse films from here on out. Even more than NOTLD, this film sets a specific tone that future zombie films attempted to either duplicate or subvert.

Zombi 2, 1979

In the ’70s and ’80s, it was hard to beat Italy in terms of fucked-up horror movie content, and given that market’s fondness for the “cannibal film,” is it any surprise they also came to love the zombie genre as well? Zombi 2 is the greatest of all the Italian zombie movies, intended as essentially a direct follow-up (thematically, not plot-wise) to Dawn of the Dead, which had been released in Italy to great success under the title Zombi. Helmed by Italian giallo/supernatural horror maestro Lucio Fulci, Zombi 2 significantly ups the crazy factor and pushed gore to a new ceiling. The effects and makeup on this film are absolutely disgusting, and it’s filled with iconic moments that have transcended the horror genre. Scene of someone having an eye poked out? Always compared to the eye-poking scene in Zombi 2. Scene where a zombie fights a freaking SHARK? Well, nobody compares that because nobody has the balls to try and one-up Zombi 2’s zombie shark-fighting scene. That’s one contribution that will stand the test of time forever.

City of the Living Dead, 1980

Lucio Fulci followed up Zombi 2 with City of the Living Dead the next year, a film that sounds like it could be more of the same but is instead a more ambitious and artistic project than the straight-up fan service of Zombi 2. Fulci doesn’t even quite hold himself to using the same kinds of creatures he used in his film a year earlier—rather than Romero zombies, these are almost like demonically empowered corpses driven up from the earth by the opening of “the gates of hell.” It’s a bit of a confusing, sprawling mythology, and a story that rambles from New York City to the seaside, Lovecraftian-named town of Dunwich. Plot is almost never a strength in these types of Italian horror flicks—the best of them become very memorable for their lurid combination of stylish color, surreal, hammy performances and shocking gore. Those are all the things that City of the Living Dead does well, like any of Fulci’s best movies, and it showcases a unique midpoint between the science-based Romero ghoul and a supernatural revenant.

Hell of the Living Dead, 1981

Okay, where the preceding film and Zombi 2 are examples of fairly well-regarded Italian zombie movies, Hell of the Living Dead is right near the bottom of the barrel. It’s a rather loathsome, grimy movie that is often in poor taste and is so opaque in its plotting that you’ll often have difficulty determining what, if anything, is happening in the story. Style-wise, the film is like a bridge between the classic zombie film and the Italian “cannibal natives in the jungle” horror genre, in the same vein as Cannibal Holocaust. Thus, it encourages all of the worst excesses of that style—Random, pervasive nudity, casual racism and tons of stock footage, some of it of real-life human tragedy. Director Bruno Mattei was an exploitation guru who has occasionally been compared to Ed Wood within the Italian filmmaking market, and the film also manages to feature some sequences directed by Claudio Fragasso, who went on to produce Troll 2 in America, one of the greatest “fun-bad” movies of all time. Hell of the Living Dead, though, is a dreary affair only notable for some decent makeup effects. It did, however, have an unfortunate influence in pushing the Italian zombie genre further down this rabbit hole of excesses and perversity, while the quality of the films decreased. Zombie movies are ultimately a cycle—they go up, they go down.

Day of the Dead, 1985

Although Dawn will probably always have more esteem, Day of the Dead is my personal favorite of George Romero’s zombie films, and it might be my favorite overall zombie movie, period. It comes along at a sort of sweet spot—bigger budget, more ambitious ideas and Tom Savini at the zenith of his powers as a practical effects artist. The human characters this time are scientists and military living in an underground bunker, which for the first time in the series gives us a wider view of what’s been going on since the dead rose. This film reintroduces the science back into zombie flicks, finally making one of the main characters a scientist (Matthew “Frankenstein” Logan) who has had some time to study the zombies in the relative safety of a lab. As such, the movie redefines the attributes of the classic Romero ghoul—they’re dumb, but not entirely unintelligent, and some of them can even be trained to use tools and possibly remember certain aspects of their previous lives. That of course brings us to “Bub,” maybe the single most iconic zombie in Romero’s oeuvre, who displays a unique level of personality and even humor. Day of the Dead ultimately takes a monster that audiences thought they knew pretty well at this point and suggests that perhaps they were only just scratching the surface on zombies’ potential.

Re-Animator, 1985

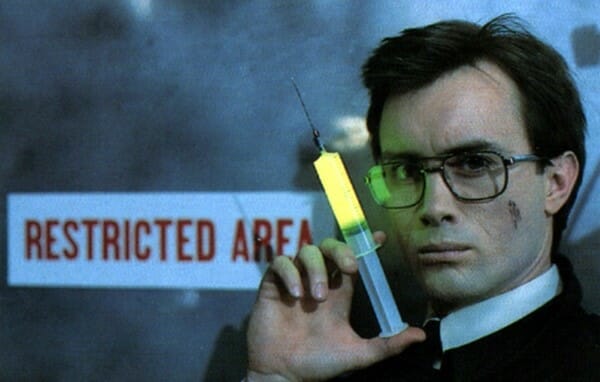

Day of the Dead brought a science aspect to reanimated corpses, but Re-Animator revels in it. This is the best kind of pulpy science, the stuff that one would have found in the pages of Weird Tales in the heyday of H.P. Lovecraft. And indeed, Re-Animator is a modernized Lovecraft adaptation from a 1921 story, still perhaps the best adaptation made from one of his pieces of short fiction. Jeffrey Combs shines in a wonderfully manic, campy portrayal of mad scientist Herbert West, who brings the dead back to life via syringes of glowing green ooze. Only problem? They freak out immediately after coming back to life and try to murder everything around them, which naturally doesn’t stop West from trying over and over and over again in the film’s lesser sequels. Re-Animator contains a streak of the black humor that would begin appearing regularly in zombie films from this point onward, even though its gore and scenes of violence are quite horrific as well. It feels like a reaction by forward-thinking director Stuart Gordon to genre fans who had started becoming desensitized to the staid atmosphere of sincere horror films and wanted to laugh at gory zombie violence rather than simply recoil from it.

Return of the Living Dead, 1985

John Russo is a huge unknown in terms of important figures in the history of zombie cinema, at least among those who aren’t big horror geeks. Russo is the man who created the original story for Night of the Living Dead alongside George Romero, and thus is essentially one half of the driving force for the most famous zombie film of all time. After the two parted ways post NOTLD, their settlement dictated that Russo would retain the rights to any future films with the phrase “living dead” in the title. Thus, Romero’s “of the dead” monikers in future films. Russo, meanwhile, instead wrote his sequel as a novel, which as then finally adapted as a film 17 years after the original NOTLD with extensive rewrites by director Dan O’Bannon. The result is one of the all-time zombie classics, a film that is equal parts gory and hilarious while making a concerted effort to capture the youth movement, art aesthetic and especially music of the mid-’80s. It’s influential in so many different ways: the comedic tone; the youth focus; the scapegoating of an American military experiment gone wrong as the genesis of the zombies. The zombies too have been completely redesigned with all-new capabilities—they’re intelligent; they can speak; they can move fast; and for the first time ever, they’re specifically targeting human brains. That last point was so influential and so ubiquitous in the genre after 1985 that it’s incorrectly been assumed by many people for decades that the Romero zombies are brain-eaters. For these reasons, ROTLD is undoubtedly one of the most significant zombie films ever.

Night of the Creeps, 1986

Night of the Creeps feels like a bastard child of both ROTLD (primarily) and Re-Animator tangentially, but it’s honestly a weirder film than either, and that’s saying something. Haphazardly blending sci-fi with horror-comedy, it’s about an invasion of parasitic alien slugs that turn their hosts into superpowered zombies. Directed by Fred Dekker, who would go on to helm the much more family-friendly Monster Squad a year later (which strangely enough, doesn’t have any zombies), it’s a risque, rather tawdry horror film set a college, and thus often feels like some kind of zombified twist of Animal House. Like ROTLD, its inherent ’80s-ness is absolutely off the charts, but it has more of a science-y, lab-based feel thanks to the presence of aliens and a presumed plot to take over the world. In this way, it’s like the zombies were used to make the kind of ’50s-style B-movie that otherwise would have starred alien invaders. They took the monster of the decade, zombies, and substituted them into an earlier style of film, ramped up the sexualization and rock ’n’ roll, and a cult classic was born.

Evil Dead 2, 1987

The obvious question to answer here is not whether Evil Dead 2 is great or whether it’s influential, but if it qualifies as a “zombie movie,” per se. The deadite antagonists are magically or demonically empowered—their bodies are inhabited, whether they’re alive or dead. The fact that many of them are reanimated corpses, though, makes me say it’s close enough—you can call them “zombies,” at least on some level, and the rural farmhouse location is almost exactly the same as in NOTLD. The film is essentially a remake of the first 1981 Evil Dead; Sam Raimi going back to an idea he clearly enjoyed with a bigger budget and more experience to “get it right” and up the ante. There are some tweaks—Ash goes from being almost a “final girl” character to a much more capable, wisecracking one right from the get-go, and significantly more of the film features him in a tour-de-force solo performance, which helps make Evil Dead 2 one of the best, most tightly paced horror comedies ever. It just wastes no time, going straight into the insanity and comic violence within the first 10 minutes and never letting up ever again. It’s a film indicative of the changing attitude toward zombies—at this point in the late ‘80s it’s becoming rare that zombies are ever treated as simply “scary.” More and more frequently, they’re instead incorporated into madcap comedies and action films ‘ala Evil Dead, and this is a trend that continued through the ‘90s.

The Serpent and the Rainbow, 1988

You can thank Wes Craven for an unexpected revival of the voodoo-style Haitian zombie in 1988’s The Serpent and the Rainbow, an unusual film based on the real-life accounts of an ethnobotanist who studied the roots of the zombie legend and the various potions and powders supposedly used to create “zombies” in Haiti. These are beliefs still accepted on some level in various communities today, but the film itself is far from grounded, and ventures into a rather outlandish caricature of voodoo beliefs. It makes for some memorable imagery—victims being buried alive, waking up screaming; voodoo magic causing scorpions to materialize inside your throat; a man’s scrotum being nailed to a chair. Wish I was joking on that last one, but I’m not. The Serpent and the Rainbow is a pretty effective reminder of why films such as I Walked With a Zombie freaked people out so effectively more than 40 years earlier.

Next: Zombies of the ’90s and beyond

Braindead, aka Dead Alive, 1992

If you’ve ever wondered to yourself about the record holder for “bloodiest film ever made,” then Dead Alive at least has to be in the conversation. A New Zealand horror-comedy by eventual Lord of the Rings helmer Peter Jackson, it’s basically the Evil Dead 2 formula taken as far and as lurid as it could possibly go. A bite from a “Sumatran rat monkey” turns the protagonist’s mother into a mutating zombie, and things simply snowball from there as various visitors and townspeople are infected and turn into rampaging beasts who have to be dispatched via absurd, comedic ultraviolence. This is not a film for the squeamish or faint of heart, even though the gore is presented in a way meant to simultaneously elicit laughs and “ewwwss.” Released in its native country as Braindead and as Dead Alive in the United States, this can be considered one of the crowning achievements of the gross-out zombie comedy. Practical effects just don’t get any ickier, slimier or bloodier than this, especially in the epic, iconic final confrontation between the hero, a room full of zombies and a remarkably gore-resistant lawnmower. How that lawnmower keeps functioning when choked with 1,000 gallons of blood, I’ll never know.

Cemetery Man, 1994

Zombies, and really the horror genre in general, went through something of a lull in the 1990s, outside of genre-savvy offerings like Scream. In Europe, though, unconventional zombie films did still pop up now and then, of which Cemetery Man is the most notable. The premise itself sounds old-school and spooky: A cemetery caretaker lives with his Igor-like assistant and kills the zombies that occasionally rise after being buried for 7 days. In reality, though, the film is essentially a horror art-comedy, an experimental and partially plotless, dreamy movie about the protagonist drifting through life without purpose and questioning why he bothers carrying out his duty. He pines after a woman who he immediately loses to zombification, and there are elements that almost remind one of American Psycho in the hopelessness and lack of identity he faces—even when the protagonist tries to commit atrocities and get caught, nobody seems to notice or care. It has the artistic flair and painterly quality of the earlier Italian films on this list, while incorporating some of the humor one might find in Re-Animator … but it’s moodier and more taciturn. It’s a film that tries to do many things at once, and is worth watching if only to shake your head consider the versatility of zombies, from simple flesh-eaters to complex symbols of entropy and nihilism.

28 Days Later, 2002

The classical zombie film was effectively dead by the time 28 Days Later came along in 2002 and completely reanimated the concept. And YES, we all know that the “infected” in this film aren’t technically zombies, so PLEASE don’t feel that you have to remind us of this in the comments. The definition of “zombies” is fluid, and always expanding. Here, they’re living rather than dead, poor souls infected by the “rage virus” that makes them run amok, tearing through whatever living thing they see. It’s a modernization of the same fears that powered Romero’s ghouls; unthinking assailants who will stop at nothing and are now more dangerous than ever because they move at a full-on sprint. It’s hard to overstate how big a quantum leap that mobility was for the zombie genre—the early scenes of 28 Days Later where Cillian Murphy is trying to navigate a deserted London in hospital scrubs and is being chased by fast-moving zombies did for this genre what Scream did for the slasher revival, sans the humor. Indeed, 28 days Later is a dead-serious horror film, and also marked a return to seeing these types of creatures as a legitimate, frightening threat. It’s indicative of another trend of the 2000s, which was to reimagine the classic rules of zombie cinema to fit the needs of the film. The Zack Snyder Dawn of the Dead remake replicated a lot of this film’s DNA when it was released two years later, although it marries the concept with the more traditional Romero ghoul.

Shaun of the Dead, 2004

Together, 28 Days Later and Shaun of the Dead established precedents for the “modern” zombie film that have more or less continued to this day. The former made “zombies” scary again, and the latter showed that the cultural zeitgeist of zombiedom (which was picking up around this point) could be mined for huge laughs as well. Most importantly, the two types of films could exist side by side. Shaun of the Dead makes a wry, totally valid criticism of modern, digital, white-collar life through its wonderful build-up and tracking shots, which show slacker Shaun wandering his neighborhood failing to even realize that a zombie apocalypse has happened. Once he and his oaf of a friend finally realize what’s happening and take up arms to protect their friends and loved ones, the film becomes a fast-paced, funny and surprisingly emotional action-comedy. Few horror comedies have actually combined the elements of humor and serious horror the way this one does in certain scenes—just go back and watch the part where David is dragged through the window of The Winchester by zombies and literally torn to pieces. It’s a film that works on so many levels, and manages to be uproariously funny while still being quite faithful to the fidelity of Romero-style zombies. Much in the same way as Zombieland (a definite spiritual successor), it shows that whether the zombies are “scary” is ultimately a matter of how everyone reacts to them. By the way—the only reason that Zombieland isn’t on the list is that I feel Shaun of the Dead encapsulates everything significant about it already. Same with Fido, a film that seems based entirely on the “domesticated zombie” gag at the end of this film.

Mulberry Street, 2006

Zombies are natural bedfellows with low-budget horror and have been ever since NOTLD. It’s simply not that expensive to apply zombie makeup and have an actor chew on some fake guts. Likewise with the found footage genre—ever since Paranormal Activity and Romero’s own Diary of the Dead in 2007, there have been dozens if not hundreds of cheap, found-footage zombie films. Mulberry Street, on the other hand, doesn’t lean on the found footage crutch, but it does look exceedingly low-budget. Still, this first feature film of capable young horror director Jim Mickle (Stake Land, We Are What We Are) feels confident and far deeper than it has to be. Depicting what is essentially a street-level zombie epidemic in downtown Manhattan, it’s like a zombie film as made by an impoverished Robert Altman, weaving together the stories of various apartment dwellers as their lives come crashing down. There have been plenty of urban zombie movies, but this one captures the feeling of powerlessness that an “average person” would truly feel during such an event, completely cut off from any kind of information on what is happening, not to mention why it’s happening. Of every film on this list, Mulberry Street might well capture the most “realistic” zombie panic, the sort of event that must have happened prior to the beginning of the events in The Walking Dead. The only downside is that it looks like a film made for $60,000, but in the vein of Evil Dead 2, it would be cool to see Mickle remake it one day with a real budget.

REC, 2007

I mentioned above that 2007 was a breakthrough year for post-Blair Witch found-footage horror, and it wasn’t only in the U.S. that people were effectively employing that technique. The best of all the found footage zombie films is still probably REC, another film on this list that exhibits some playfulness in redetermining exactly what a “zombie” is or isn’t. The Spanish film follows a news crew as they sneak inside a quarantined building that is experiencing the breakout of what essentially appears to be a zombie plague. The fast-moving infected resemble those of 28 Days Later and are later revealed to be demonically possessed in a way that moves through bites, ably blending traditional zombie lore and religious mysticism. It’s a capable, professional-feeling film for its low budget, and there are some excellently choreographed scenes of zombie mayhem that feel all the more claustrophobic for being filmed in a limited, first-person viewpoint. Zombie horror seems to go hand-in-hand with the found footage approach more naturally than some other horror genres—perhaps it’s the fact that in the digital age, we’d all be compelled to document any such outbreak on our phones or other devices? Regardless, it’s not nearly so forced as some entries in this particular horror subgenre, and gives an excellent sense of what it might be like if you were just an average person locked in a huge apartment building filled with zombies.

Deadgirl, 2008

The 2000s was a decade of taboos falling, but zombie sex is still probably a bit much for many audiences. And yet, that’s pretty much the entire central theme of Deadgirl, certainly one of the most WTF zombie films that has come along in recent memory. You have to give it to the writers—no one had really thought about the possibility of zombies with sexuality before this. Unfortunately, it’s compulsory sexuality, as the “deadgirl” character in question is discovered by a handful of teenage boys, most of whom spend the majority of the film arguing over who gets to rape her next. It wants to ask some kind of question about “what would you do?”, but considering that one half of the options involve necrophilia, the choice doesn’t seem all that hard. The film is effectively creepy and gross, as you might imagine, and makes the list simply for suggesting an application for zombies that hadn’t been explored in this depth in the 40 years between this film and NOTLD. Like it or hate it, any and every instance of zombie sex in the future will always be compared to Deadgirl in some way.

Pontypool, 2009

Pontypool is one of the most cerebral and ethereal re-imaginings of what the word “zombie” might be taken to mean, and it’s a film that I respect immensely for taking the hard road. Zombie fans (and horror fans in general) are a fickle bunch—we want things we haven’t seen before that also reflects everything in the history of the genre, which is a near-impossible task. Pontypool doesn’t bother at all with zombie convention. Rather, its antagonists, which are never called “zombies” and are occasionally referred to as “conversationalists” by director Bruce McDonald, are a criticism of 21st century humanity’s inability to truly connect and discuss pertinent, truly significant issues. There is indeed a “zombie virus” here, but it’s not transmitted through bites or blood, but by ideas, by the very English language, which has become so watered down with pleasantries and insincerity that it’s taken on a destructive life of its own. The film ultimately contains all of the gore and violence you would expect from a great indie zombie film, simply delivered in a unique way, with a distinctly new message. It’s a truly postmodern zombie film and deeply dissatisfied jab at society itself.

Juan of the Dead, 2010

What is it about zombie films that compel small-time filmmakers to dream big? Juan of the Dead is billed as Cuba’s first feature-length zombie film, and it’s a remarkably confident piece of work from director Alejandro Brugues. It has some similarities with a somewhat more sober-minded Shaun of the Dead beyond the title—the main character is also a slacker with a slob of a best friend, but the tone is much more impoverished and street-level than the white-collar boredom of Shaun’s life. Juan of the Dead brings back some of the political verve to zombie cinema, with many Cubans assuming that the communist country’s zombie issues have something to do with “capitalist dissidents.” Juan, our hero, attempts to profit off the panic and confusion by starting an enterprising small business: For a fee, he and his crew will come to your home and dispose of your zombified loved ones. Of course, it eventually spins out of control, and his family and friends get wrapped up into the military’s larger fight against the zombies. It’s a well-balanced film that hits just enough horror, comedy and emotional notes, and one that raked in plenty of independent film awards. There are individual moments that distinctly recall George Romero’s films in a way that goes beyond simple imitation to stand ably on their own.

The Battery, 2012

The concept of a low-budget zombie drama is one that has become fairly common in the 2010s, likely owing to the influence of The Walking Dead and games such as The Last of Us, which treated zombies more like a set-piece to allow human drama to take shape. The Battery is an extrapolation of this format, a story about two men, a former baseball pitcher/catcher duo, traveling across the country together in the wake of a zombie apocalypse. And as for plot? That’s pretty much it. It’s a self-contained film that leans entirely on the performances of two actors, showcasing the ways that two men with vastly different personalities handle the mental strain and emotional challenges of continuing on each day and finding a reason to exist. The zombies are there, but they don’t really feel like active antagonists, as it were—they’re more like a constant roadblock and painful reminder of everything these men have lost in their former lives. It’s a film that almost mirrors the struggle of just getting out of bed in the morning to tackle another day—call the zombies your neighbors, your coworkers, etc. That’s what zombies have become today: A walking representation of 21st century ennui.

Jim Vorel is Paste’s news editor, and he remembers a time when he thought he would be one of only a few people interested in a Walking Dead TV series. You can follow him on Twitter.