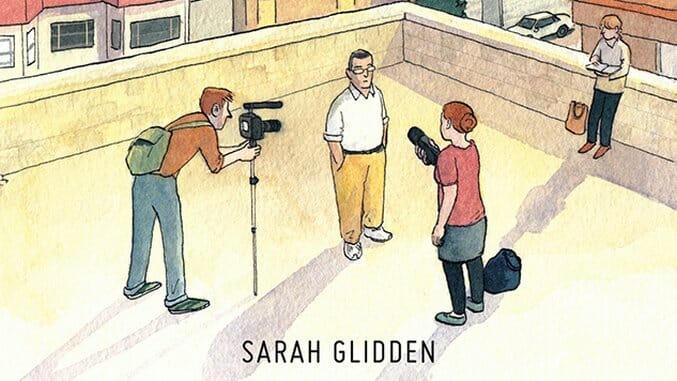

Exploring the Untold Stories of Refugees with Rolling Blackouts Cartoonist Sarah Glidden

Comics Features Sarah Glidden

When we discuss atrocities like the Gulf War, it’s simpler to think of the conflict as purely political, glossing over the millions of voices silenced by coalition bombs.

Sarah Glidden’s compelling new graphic novel, Rolling Blackouts, explores the untold stories of political and war refugees in Iraq, Turkey and Syria. Following a group of Seattle journalists, the nonfiction work gives a rare insight into the real people behind the statistics, along with the ethical questions faced by Western writers tasked with reporting in politically charged locations.

One of the most compelling narratives in Rolling Blackouts comes from Sam, a former US immigrant who was imprisoned for five years before being deported on terrorism charges—charges he vehemently denies. The dichotomy of Sam’s affable nature and the serious crimes he’s accused of makes for a fascinating character study. His forgiveness for the men and women who facilitated his capture and deportation, along with the evident heartbreak over the absence of his wife and children make succinct conclusions about his situation tough to find.

And much like that scenario, little to nothing in Rolling Blackouts is black and white. The team discovers that Saddam Hussein’s monolithic prisons—once used to torture and imprison Iraqi Kurds— now serve as permanent living spaces for the families whose homes were destroyed in the violence.

The posse of journalists are joined by Dan, a former marine looking to change his own perspective on the role he played as a soldier. His story is also fascinating, if only to see the mental gymnastics Dan requires to juggle his personal pride against the stark realities of post-war Iraq.

Paste spoke with Sarah about the challenges she experienced while on location and some of the puzzling ethical questions journalists face while reporting in the Middle East.![]()

Paste: You mention the rolling blackouts of Sulaymaniyah in your work—what was the reason behind making this the main title?

Sarah Glidden: The title does refer literally to the rolling blackouts we experienced in Northern Iraq. The first time we experienced them we were a bit surprised, but no one else around us was. It was an inconvenience that had become a part of life, and before long we were accustomed to it as well.

But the phrase also made me think about movement, memory and storytelling, which are really the major themes of the book. Everyone we spoke to was displaced in one way or another, and the act of telling a story, especially when trauma is involved, is always complicated and involves editing, gaps due to the desire to protect oneself, and forgetting.

Paste: You mention early on that you had to be careful not to put yourself in the story too much. What were the other challenges you faced during your trip?

Glidden: My role during the trip was to really step back from the interviewing and not get too involved with any of our sources, but that was challenging in and of itself. The people my journalists were speaking to had lived through experiences so different from my own, and the temptation was always there to ask them my own questions, which wouldn’t have been appropriate at the time.

It was especially difficult when it came to people like Dan, the ex-Marine who was with us and who one of the journalists, Sarah, was interviewing for an article as we travelled from place to place. He and I were often together without her, so of course we talked about things, but I needed to be careful about not discussing things with him that she might want to talk to him about for her piece. This didn’t always work.

Rolling Blackouts Interior Art by Sarah Glidden

Paste: What do you think is the role of Western journalists in Syria, Turkey and Iraq?

Glidden: This is something we talked about a lot, and which the journalists I was with have been mindful of since they first started reporting together from abroad. There are some people who think that Western journalists shouldn’t be the ones telling the stories of others, as they can’t truly understand what it’s like to be Iraqi or Syrian or anyone else; those people should be able to tell their own stories without American filters.

It’s definitely true that we need more stories written by the journalists native to other countries, as well as first-hand narratives by non-professionals, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a very important role that American or other foreign journalists play.

A reporter knows their own community. They know the context that their readers might bring to a story, and they (hopefully) know how to talk to them in a way that they will listen. When it comes to Iraq and Syria, this is especially important. I think American journalists have a responsibility to convey the complexity of the conflicts that our government started or is involved in. And when it comes to things like the refugee crisis, first from Iraq and now also from Syria, journalists have the task of refuting a lot of misinformation that is out there, often coming from people in positions of power.

Paste: When you arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan, were you surprised by how openly pro-American the residents were?

Glidden: I was surprised, yes, but it began to make sense the more we talked to them and understood the unique relationship between the Iraqi Kurds and the United States. There are definitely limits to that good feeling, however. The US has helped the Kurds in the past, and continues to support them today, but that help has most often been in service of American interests, which means we’ve really screwed them over when that support became inconvenient.

Paste: I found Rolling Blackouts to have a really calming mood and honest tone despite the challenging subject. I think graphic novels generally can create a greater sense of atmosphere than prose nonfiction. What do you think graphic novels offer in terms of storytelling compared to other media?

Glidden: There are definitely advantages and disadvantages to using comics for storytelling, and sometimes they’re one and the same. That sense of atmosphere you mention comes in part from the fact that you need many panels and pages to convey information or dialogue that would take less than a page if it were described using only text. It’s a luxury to have 300 pages of book to tell a story like this one, but it gets very difficult when you’re trying to make a shorter article. There aren’t many magazines or newspapers that are willing to give up several pages for a comic. Thankfully we have the internet now!

I also think that comics and graphic novels have the potential for really connecting a reader to characters or settings. We’re so used to seeing text and photographs, that looking at hand-drawn images brings a certain warmth to that relationship, I think. I always hope that my work can be a gateway for people. Maybe they’ll be more likely to read a comic about Iraqi refugees than one of the many articles and books out there that go into greater depth, but hopefully once they read the comic, they’ll feel a connection to the subject and want to find out more. Comics journalism is a companion to prose, radio or documentary, not a replacement.

Rolling Blackouts Interior Art by Sarah Glidden

Paste: After five years of detention and being deported, I was really surprised by Sam’s forgiving attitude towards his captors. On reflection, what are your own feelings about Sam and what happened to him?

Glidden: I can’t know what Sam’s true feelings are, but I have a feeling that he kind of needed to feel some sense of forgiveness in order to keep going. At this point, he is separated from his family and that’s the cause of an enormous amount of pain for him.

If that pain were also accompanied by rage, it might be too much to bear. But maybe he simply wanted to put on a good face for us, to play the role of a forgiving man. I still think that maybe he thought this documentary about him might help his case in the future, and if that’s true it would make sense that he would want to hide any feelings of bitterness or resentment.

Paste: After what’s happened in Syria following your trip, how do you feel about the plight of the refugees being displaced yet again?

Glidden: It’s really heartbreaking. I don’t know how else to put it. I know that some of the people we spoke to were forced to go back to Iraq, which still isn’t safe, and some of them went on to third countries like Turkey or Lebanon, which is still very difficult even if it isn’t life-threatening.

What makes me the most upset, however, is seeing how little people in the US understand about the refugee resettlement process. Any refugee that makes it to America has gone through multiple interviews, medical exams and extensive vetting that sometimes takes up to two years. Once they arrive, they need to get jobs and start working quickly and they even have to pay back the cost of their plane ticket to get here. We could be resettling tens of thousands more Syrian and Iraqi refugees the way Germany or Canada have been, but because there is so much political resistance to that, we are barely doing our part.

The US resettles the highest number of refugees by number (not per capita) in the world, and we have been especially welcoming in the past to refugees from countries like Vietnam and Cuba. So it’s not like we don’t know how to be welcoming. We could be doing better.