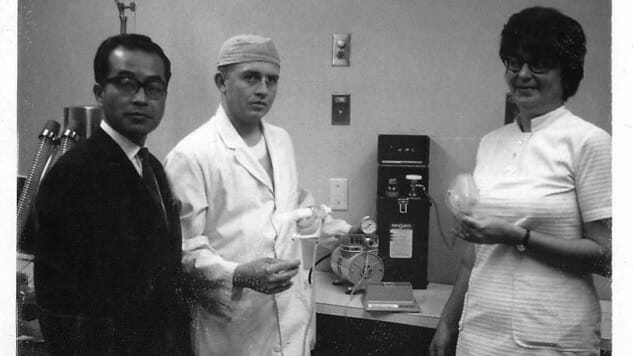

Pictured: The author’s father, William Chae-sik Lee.

Even as the daughter of Korean War refugees, I consider myself a New Yorker. But when people find out I was born and raised in all-white northern Minnesota mining town just a stone’s throw from Canada, the question inevitably follows: “How did your family end up there?”

“My father was a doctor,” I say. When I asked my parents, all they would ever offer was, “That’s where the job was.”

My father was born in Pyongyang in 1926. Against all odds, he made it to South Korea as a teen and managed to gain admission to the prestigious Seoul National University Medical College. During the Korean War, because of his excellent English, he was selected to be a liaison officer, shepherding various U.S. military officials, including General Matthew Ridgeway, when they visited hospitals and MASH units.

These contacts set my father’s immigration in motion. Though a doctor, all FTPs—foreign trained physicians—had to spend a year repeating their internships. My father did his in Jim Crow-era Alabama at a hospital that commonly hired FTPs to staff the segregated wards. A professor my father met during the war brought him to the University of Minnesota where he worked with Dr. C. Walton Lillehei, the “Father of Open Heart Surgery”. My father became one of the first people in the world to administer anesthesia during open-heart surgery.

After completing his residency, my father still had a major problem: he was only in America on a temporary student visa. The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1924—established during one of America’s peak times of xenophobia against Asians—set quotas based on country of origin. The quota for Korea, where the U.S. had just fought a war, was zero. Luckily, Hibbing General Hospital, which served a small mining town in a place where temperatures often stayed below zero for much of the winter had been unsuccessfully searching for an anesthesiologist and was willing to take a risk with my father.

Most of the doctors at the hospital were “home grown” but a good anesthesiologist was hard to find. In a small town, a lone practitioner had to take on all its demands—routine and emergency surgeries, childbirth, pain—round-the-clock. Thus, the anesthesiologist in the closest urban area, Duluth, 80 miles away, was also an immigrant. Hogan’s Hero-accented Bernhard Boecker worked in a group practice and therefore could occasionally cover for my father, and they became close friends. I can’t help wondering what my father thought when “Uncle Bernie” went on to become a citizen as a matter of course, while my father and mother received deportation papers the day I was born.

The hospital and town feared losing my father almost as much as my father feared deportation. Patients knew what the loss of the long-sought doctor “who put people to sleep” would mean and came out in droves to sign a petition to be brought to the State Department. The petition was rejected on the reasoning that, besides not wanting to set a precedent, if my father received an easement, the equivalent of a green card, he’d leave Hibbing first thing. That would be what any sensible person would do.

A last-minute twist at the State Department granted my parents a stay. However, he was still an “alien ineligible for citizenship.” This meant he was never quite on solid ground about his immigration status, he also could not travel back to Korea and expect to be let back in.

But he kept his word and stayed at Hibbing General Hospital for forty-plus years. He’s passed on now but I know those weren’t always the happiest times of his life. My father overcame extraordinary odds to be educated during the Japanese colonization of Korea and then to gain entrance to Seoul National University. And, as an immigrant, to be part of medical history in the U.S. He probably didn’t think the Pyongyang-Seoul-Birmingham-Minneapolis trajectory of his career was going to end in tiny Hibbing, Minnesota, but it did.

Just as there are no atheists in a foxhole, no one lying on an operating table awaiting surgery actually wants a Trump immigrant ban. On January 27, President Trump signed an Executive Order that, among other things, barred admission for anyone coming from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen, an odd echo of the Immigration and Naturalization Act that barred my own parents.

While the Trump ban’s name screams “PROTECTING THE NATION FROM FOREIGN TERRORIST ENTRY”, its hollowness is evident in citing 9/11, as none of the countries banned spawned any of the 9/11 hijackers. And how about “the wall” to be built between the U.S. and Mexico? While Trump is so scared of Mexico, does he realize there are doctors all over the world and it’s their exchange of ideas bringing about scientific progress? Our son, for instance, had a neurological condition for which we learned one of the leading doctors was in Mexico. We traveled there for a treatment whose results drew admiration from our son’s Brown University neurologist. We should be glad Mexico isn’t building a wall to keep us out.

During this election season, I recognized many of the “heartland voters,” many who are hurting financially, physically, and spiritually, and who see in Trump someone who is going to save them and keep them safe. But do these people who voted for “the wall” and “the ban” know that international medical graduates made up more than 50% of the internal medicine residency slots in 2016, i.e., precisely the doctors who work with underserved populations like the rural and veterans? And that, as the New England Journal of Medicine reported, of all U.S. physicians, 24% are international medical graduates, and of them, immigrants from Muslim-majority countries dominate.

A Harvard study recently revealed that patients actually have a lower mortality rate with foreign-trained medical graduates

Anti-immigrant voters may not realize that not only is Trump not going to save them, but his policies may bar some people who might.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee is a novelist and essayist who teaches at Columbia. Find her on Facebook and Twitter.