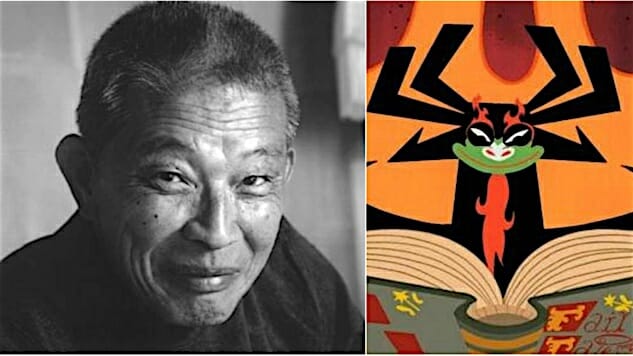

Remembering Mako

As Samurai Jack returns, the trailblazing actor who voiced his ultimate foe will be sorely missed.

Movies Features Mako

Once again I am free to smite the world as I did in days long past.

—Aku, the Master of Masters, the Deliverer of Darkness, the Shogun of Sorrow, etc.

“He was one of the early truly trained actors who was able to take stock roles, roles seen many times before, and make an individual a live and vibrant character.”

—George Takei, in Mako’s obituary in The New York Times, 2006

There’s no contest: Samurai Jack is the ultimate hero. He’s born of noble blood. He’s got an indestructible magic katana that was forged by the gods from his own father’s soul and whose blade harms only the unrighteous. He’s been trained from boyhood in every deadly art by the baddest fighters of every Old World culture from Shaolin monks and Mongolian cavalrymen to the ancient Romans and Robin Hood (somehow). And yet, it’s not any of these things that make him truly great. Rather, it’s the evil he faces.

Aku is a towering, form-fluid personification of pure sadism, ego and greed. Introduced as an evil shapeshifting wizard, the show eventually retconned him to be an errant fragment of some unknowable malice from the very dawn of creation. He conquers the entire world and reduces it to a polluted, lawless post-apocalypse. He belongs in the same pantheon of baddies as timeless foes like the Joker or Voldemort.

And there’s a very good reason his booming, gravelly voice provides the show’s opening exposition, or that his thundering taunts often outnumber the hero’s lines in a given episode: That voice was Mako’s.

As a generation of hyped up fans eagerly await the return of Samurai Jack in just a few days, I’m sure I’m not the only enthusiast who feels anew the loss of Mako Iwamatsu (1933-2006), whose physical stature was as slight as his voice was mighty. Since you—the person reading this article right now—are no doubt well into a back-to-front binge watch of all four seasons of Jack on Hulu, it’s a good time to look back at a trailblazing actor who could play the most humble, the most wise, the most bumbling, and the most evil with such inimitable charm that he needed only one name.

A Man of the East and the West

Born in Kobe, Japan, in 1933 to parents who wrote and illustrated children’s books, Iwamatsu Makoto experienced the Second World War as a boy under his grandmother’s care. His parents left to study art in the United States, avoiding internment because they lived on the East Coast. It was only after the war that he rejoined them there and eventually became a naturalized U.S. citizen. The young immigrant settled in California and, after an abortive attempt at learning architecture, became fascinated by the stage. So much so that he dropped out of school, he said, screwing up his draft deferment in the process. A two-year stint in the military gave him opportunities to travel throughout Asia and reconnect with his heritage.

Fellow Japanese-American actor George Takei remarked that Mako faced struggles in his career because he was an immigrant.

“There was the linguistic challenge,” Takei said. “But he recognized we needed more opportunities to practice our craft.”

The Godfather of Asian-American Theater

Determined nonetheless, Mako pursued a stage career and founded The East West Players in 1965. The stage company was aimed at nurturing Asian actors.

“We started talking about … [how] most of us were caught being stereotyped in television and movies whenever a bunch of us would work together, and that went on for several years,” Mako said in a 2000 interview. “Finally, in 1965, we said: ‘We gotta do something … we gotta do things of our choice. We can’t wait for someone to say, hey, you guys gotta do something-we can’t wait for that.’ So, that’s how we started East-West Players.”

Mako wanted to demonstrate that Asian actors didn’t need to play simple bit parts, “to show we are capable of more than just fulfilling the stereotypes—waiter, laundryman, gardener, martial artist, villain,” he said.

Fighting to transcend those limitations on an Asian actor would define Mako’s career.

The East West Players made history in 1976 when they staged Pacific Overtures, a Sondheim musical about the United States’ diplomatic strong-arming of Japan in 1853 told entirely from the Japanese perspective. The production starred an all-Asian cast that included Mako, who got himself a Tony nomination. It was the first musical he ever performed in.

“I remember we went to the Tony Awards to do a number from the show, and we got there by bus,” Mako recalled to The Sondheim Review. “But after the show, we had to walk back to the Winter Garden to get out of our costumes. As we were walking, and some of us were in Kabuki makeup, some of the people on the street were yelling, ‘Hey, why don’t you all go back to China?’ On the one hand, we felt we were making progress in the theater, but socially we were getting comments like that.”

For his own part, Mako claimed he wouldn’t have accepted his Tony for Pacific Overtures even had he won it, just to call attention to what he felt was unfair treatment of Asian actors.

“I wasn’t going to accept it. I was going to refuse the Tony,” he said. “Why? Asian-American actors have never been treated as full-time actors. We’re always hired as part-timers. That is, [producers] call us when they need us [for only race-specific roles]. If a part was seen as too ‘demanding,’ that part often went to a non-Asian.”

The company also trained writers, including David Henry Hwang, the playwright responsible for M. Butterfly.

“Unless our story is told to [other] people, it’s hard for them to understand where we are,” Mako said of the company’s expansion into nurturing playwrights.

By one estimate, about 75 percent of every union-represented Asian actor in Hollywood has worked at some point with The East West Players. Some of the group’s alums include Takei, Pat Morita, Harold and Kumar (John Cho and Kal Penn), B.D. Wong, and Dante Basco (who would share the voiceover booth with Mako in Avatar: The Last Airbender, the animated series that incidentally held the Best Cartoon Ever crown after Samurai Jack).

“What many people say is, ‘If it wasn’t for Mako there wouldn’t have been Asian-American theater,’” said Tim Dang, an artistic director of East West Players. “He is revered as sort of the godfather of Asian American theater.”

Unforgettable on Screens Big and Small

Mako’s big screen career was also taking off by the mid-’60s. In 1966, he was nominated for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for what would otherwise have been a minor role in The Sand Pebbles.

It was exactly the “stock role” Takei claimed that Mako often elevated through his lively performance. Though the character of Po Han was a minor one and an Asian in a movie where the overwhelming majority of speaking roles were white, it nonetheless caught the Academy’s eye. So would Mako’s turns in TV shows as diverse as Fantasy Island and Walker Texas Ranger, or movie roles like Conan the Barbarian’s wizard companion Akiro and Duncan MacLeod’s sage master in Highlander: The Final Dimension.

There’s a theme there, and unfortunately it’s the same one he railed against as an advocate for Asian actors: Mako was always cast as a second-tier character. It wasn’t until he really broke into recent animation shows that he became the sort of major character around which an entire story hangs. Ask any Jack fan, and he or she will readily tell you that the show simply wouldn’t have been the same thing without its insidious antagonist. For a young generation of fans who tuned in to Samurai Jack to have their faces rocked off, Mako was very much one of the show’s standard-bearers: His roaring opening narration was prominently featured in the marketing run-up to the show’s debut and creator Genndy Tartakovsky touted him in the supplemental materials.

Fans of his instantly recognizable voice didn’t need to wait long for him to return to the booth again in Avatar: The Last Airbender, a show just as ridiculously epic. The role of Iroh—a calm and friendly character with his own tragedies, goals and philosophical musings on how to properly shoot kung fu fireballs—was one of Mako’s last. He succumbed to cancer before the last season of the show. One of his last episodes, “Tales of Ba Sing Se,” has Iroh visit the grave of his own son as an In Memoriam to the actor pops up.

“Not in My Lifetime.”

I’m part-Asian myself, and as I’ve lamented before, when you come from an immigrant family, you don’t often see your story. Dang, Mako’s theater contemporary, once related that the actor wondered if the theater company he’d founded would ever be unnecessary because Asians could simply count on the same roles as white actors, and in answering his own question said simply, “Not in my lifetime.”

It’s depressing to look around and realize that after a lifetime of tireless work in and out of the spotlight, Mako was right. In his screen roles, he was eternally a supporting character rather than the lead, and even in his most prominent and most complex roles, Mako was often a voice rather than a face. This is still the landscape Asian actors face.

Some outlets report that Greg Baldwin will be his “sound-alike” in Samurai Jack, as he was in Avatar. No disrespect to Baldwin, who does admirable work, but those reports are wrong. There’s no such thing as a “sound-alike” for Mako Iwamatsu.

Kenneth Lowe is a media relations coordinator for state government in Illinois. His work has appeared in Colombia Reports, Illinois Issues magazine, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.