Pure Comedy lives up to its title. It’s a comedy in every sense of the word. Absurdity is the order of the day. There are jokes around every turn. The central joke being the perfectly dissonant balance of sincerity and sarcasm conveyed by music and lyrics alike.

It makes sense Father John Misty is a polarizing figure given how much his music is composed of polarities. That’s truer of this album than it is of even the very sardonic I Love You, Honeybear. Much has been made of the marriage of his conventionally beautiful voice and accessible instrumentation to his nihilistic and irony-soaked lyricism. This record is definitive proof that that relationship is working, lasting and getting better with age.

This is a big-idea album in a way none of his work was before. Even with songs like “Holy Shit” or “The Ideal Husband,” he’d fall back on his own personal experiences to—at least, ostensibly—give his larger ruminations a sense of foundation. This time around, he musters all his confidence as a philosopher to portray externalities from an outside-looking-in perspective. On the whole, his potential need for introspection has been removed in the service of a greater cause: describing the world in all its tragicomic glory.

The title track serves not just as an entryway into those larger themes but a summary statement of all that’s to come. The cards are on the table and his worldview is explained with a voice as delicate as his observations are harsh. His mockery of birth, death, religion, consumerism, politics, etc. is matched with piano chord progressions pining for a solution to all the problems posed by his lyrics. The only earthly forces his barbed wit doesn’t attack are love and loneliness: “I hate to say it, but each other’s all we got.”

Life is a joke, so how can Josh Tillman tell it best? “Total Entertainment Forever” looks at it from the perspective of fulfillment. A world of pleasure, VR sex with celebrities and round-the-clock amusement on TV: it’s too close to home and he knows it. One of the best ways to show the purposelessness of existence is to show what it would mean for any given desire to be satisfied. A life of endless joy and entertainment is many people’s idea of heaven. It certainly shouldn’t be and here’s the song to prove it.

But perhaps the listener doesn’t need to be reminded of why being plugged into a pleasure hub wouldn’t be as great as it sounds. For these more enlightened souls, “Things It Would’ve Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution” is a reminder that their more high-minded ideas are similarly futile. Perhaps we return to a world of noble savages, perhaps we destroy capitalism, perhaps we stop thinking in terms of price tags. The gag here is even if such a revolution were to transpire, “There are some visionaries among us developing some products / To aid us in our struggle to survive / On this godless rock that refuses to die.” A reset on the human experiment would do nothing to remove its ailments.

His main source of dissatisfaction seems to center around the idea of humanity’s insatiable desire for importance. This takes the form of organized religion (“When the God of Love Returns, There’ll Be Hell to Pay”) and politics (“Two Wildly Different Perspectives”) and…everything else. As Tillman states in the title track, “These mammals are hellbent on fashioning new gods / So they can go on being godless animals.”

For his detractors, Tillman even gets a barb in at his own personality type on “Ballad of the Dying Man”: “So says the dying man, ‘Once I’m in the box, / Just think of all the overrated hacks running amok / And all of the pretentious, ignorant voices that will go unchecked / The homophobes, hipsters and 1% / The false feminists he’d managed to detect’ / Oh, who will critique them once he’s left?” Doesn’t this sound like a smarmy critique of his own work on his last two records?

Ironically, the record also contains his most achingly personal song since his J. Tillman days. “Leaving L.A.” is a slow crawl focused on the shortcomings and successes of his own life, and it’d be a tough quest to find a memoir song as good at its job as this one. For 13 minutes, he details what his own days have been like in the bleak world he’s been describing. His openness here should be proof enough there’s more to his music than pure pretension. His beloved sense of irony isn’t a defense mechanism or an egotistical self-indulgence. It’s his way of conveying the same sort of brutally honest affection for humanity and the world as Kurt Vonnegut or any other great satirist.

The most vulnerable he gets, however, is on the final track, “In Twenty Years or So.” After all the jokes, all the depressing realities detailed from the beginning of the album to the end, he gets his second round of drinks with a friend, hears a piano playing “This Must be the Place (Naive Melody)” by Talking Heads and feels like it’s “a miracle to be alive.”

Perhaps that’s the greatest joke of the whole album. That, ultimately, music and community-in-communication—the two things Pure Comedy gives us—are what make our meaningless lives worth living. That despite of how pathetic our species is, there’s still something awe-inspiring about this “speck on a speck on a speck” existence of ours. And that we want to sing and change the world for the better, even if we know it’s futile. All the irony, all the nihilist absurdism, is to get us to this point: one where we are content with our own meaninglessness.

His final words on the album are “There’s nothing to fear.” After all his unrelenting honesty prior, I’m inclined to believe he’s right about that too.

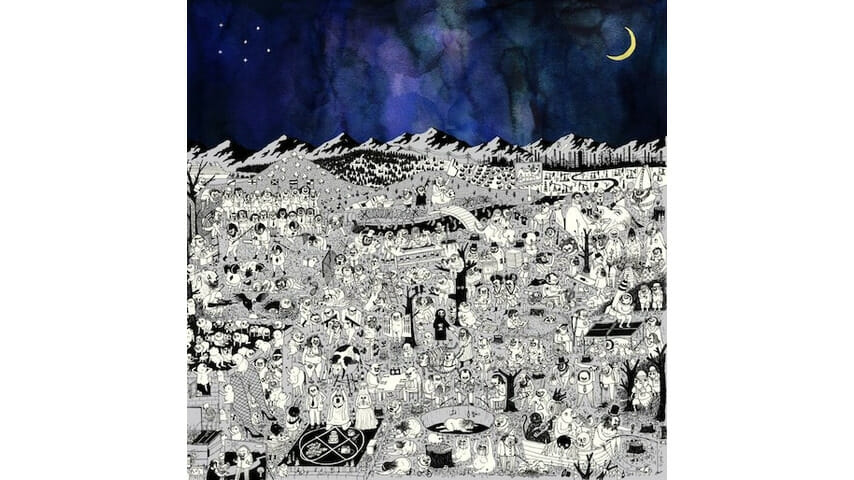

Don’t miss our cover story on Father John Misty, taken from the first edition of our new Paste Quarterly.