The Cinema of D&D Satanic Panic Seems Even Sillier Today

The roleplaying game faces a reckoning today that reveals just how ridiculous the earlier controversy was.

Geek Features dungeons and dragons

Dungeons & Dragons, like superhero narratives and videogames, has moved into the mainstream of entertainment in ways that a couple decades ago would have seemed impossible. The game has gone from an easy punchline to something television hosts bond over. It’s being used as a form of group therapy.. At least one archaeologist has called it nothing less than the first new form of tabletop game in milennia.

This has happened in part because the game has become progressively more accessible as each new edition of the game has come out. (It’s currently in what it calls its Fifth Edition.) Stereotypical depictions of the pastime have always mercilessly poked fun at the nerdy male gamers people assumed were the core audience, but it’s become increasingly clear that’s an inaccurate picture: A 2017 survey showed that nearly 40 percent of the players are women.

My own gaming groups also contradict these old assumptions: In 15 years of gaming, I’ve shared a table with Black players, women (cis and trans), gay and lesbian players. Nor has the older generation that originated the game put this particular toy away, if some of the groups I’ve been in are any indication.

It is perhaps because of this increasingly broad popularity that the past year has brought something of a reckoning to the game just as its player base has exploded. Created in the 1970s by a group of men in the Midwest, Dungeons & Dragons is firmly rooted in a lot of the genre fiction that Baby Boomers and their parents consumed as kids: Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Howard’s Conan the Barbarian character, and even Hong Kong kung fu films have imparted their DNA to the lore, mechanics and underlying assumptions of the game.

It’s that very stuff that’s now under scrutiny as D&D is being reexamined and challenged on some of its source material’s implicit biases now. The game’s assumption that there are whole species of sentient creatures who are just irredeemably evil too easily evokes ugly worldviews in the real world—and isn’t that far removed, for instance, from some of the game’s more problematic inspiration. The company that currently produces the game, Wizards of the Coast, has publicly committed to addressing this at the same time it has drawn criticism for a work culture some have accused of being dismissive toward non-white, non-binary perspectives.

All of this is wild when you consider that the hobby’s biggest problem, not even 40 years ago, was that it was under attack from the country’s right wing because parents and churches had convinced themselves the game was satanic. The trend was so widespread, they even made at least two very bad movies about it.

Daniel: That’s pretty far out.

Detective: Mazes and Monsters is a far out game: Swords, poison, spells, battles, maiming, killing.

Daniel: Hey it’s all imagination!

Detective: Is it?

The full-blown moral panic over D&D started around 1980, when a teen who played the game went missing for a while and later committed suicide—another high school student who also played the game also committed suicide in 1982, prompting his mother to form an anti-D&D group. If this sounds familiar to those of us who were around during the hand-wringing over videogames in the ’90s, it’s because all moral panics follow precisely the same tired script. Hobbies that are incredibly popular draw in many people, and some of those people struggle with risk factors that can potentially cause them to harm themselves or others. Fill Wrigley Field with people and ask anybody with a drinking problem to raise their hand: Does baseball cause alcoholism?

D&D got under people’s skin for reasons sociologists will doubtless be studying for years to come, so it was inevitable, really, that some folks would try to exploit the fearmongering with some lurid horror movies. At least two films, both of them hilariously and bafflingly bad, came out of the trend just a year apart: 1982’s Mazes and Monsters and 1983’s Skullduggery. Poor Wendy Crewson stars in both, one of the most depressing typecasting factoids I’ve ever run across.

Mazes and Monsters is by far the easier of these to locate by the virtue of the fact freaking Tom Hanks is in it. The TV movie was based on a novel by Rona Jaffe, which in turn was “inspired” by the real-life events surrounding the death of the teen in 1980.

Hanks plays a college student heading off to college, introduced as his drunk parents snipe at each other on the car ride over. He falls in with a group of people who play “Mazes & Monsters,” among them a guy whose parents are yelling at him to get a real job in software design instead of the videogames he wants to make. The others are a kid with a talking bird who is wearing a different stupid hat in every scene of the movie and who goes on and on about how great it would be to commit suicide, and the girl (Wendy Crewson).

Watching Mazes and Monsters is a bizarre experience. It is a bemusingly conservative movie in every way. The film opens in medias res on the police search for Hanks’ character, a hardboiled reporter asking the gritty cop what happened. The cop tells him he thinks the kid was playing “one of those fantasy role-playing games” in the same tone of voice Ice-T uses on Law & Order: SVU. After the movie flashes back, we find Hanks became obsessed with the game and his character in it, finally dissociating from himself completely and wandering about under the impression that he is his character.

His friends find and stop him before he jumps off the World Trade Center skydeck, but the damage is done: He’s suffered a permanent psychotic break and still sees his friends as their D&D (I’m sorry, uh… M&M?) characters. It’s okay, though; he’s happy back at home, comfortable and in the care of his abusive, negligent parents. Crewson is writing a novel, and their other friend has seen the error of his ways and abandoned his computer game dreams, missing out on the ground floor of what is now a multibillion-dollar industry. The important thing is they haven’t disappointed their stifling, controlling parents!

Skullduggery is the tougher watch—a movie featuring stars whose Charisma scores in real life can’t be higher than a 6, stuffed with scenes that make zero sense no matter what context you think they’re occurring in. Adam (Thom Haverstock) is a deadpan young man who spends his days working as a costume designer at a local theater and his nights playing a D&D-like game with Barbara (Crewson again) and her friends, run by a strange elderly man. As they game progresses and Adam keeps winning, it all becomes too real for him and he starts hunting down and murdering women as if they are objectives for his character.

This is interspersed all throughout with scenes of some sinister figure putting together a jigsaw puzzle, a recurring background character wearing janitor overalls with a slowly progressing game of tic-tac-toe on the back, and the appearance of a stage magician whose tricks entirely depend on the camera cutting away. I can’t explain any of it to you because I don’t understand it. It is a movie that couldn’t possibly have had a full shooting script in any complete order while it was being made.

It’s hard to find contemporary reviews of either of these, but the assessments in later years have treated them with opprobrium, and it’s not hard to see why: They’re rooted not just in terrible scripts and embarrassing performances, but ironclad ignorance of the phenomenon they’re seeking to exploit. D&D, simply put, just doesn’t work the way it’s portrayed in these movies. As any veteran of hobby shops and long-running gaming groups with members drifting in and out will tell you, any problems around the table are brought there from the outside.

More infamous than the dice-sploitation trend at the movies, though, is the Chick Tract about D&D that came just after them, “Dark Dungeons.” If you’re unfamiliar with the works of the late Jack Chick (how I envy you), the relevant information is that he was a cartoonist who produced evangelical tracts in comic form, many of which straddle the line between moral alarmism and outright hate speech. He wrote “Dark Dungeons” in 1984, and it’s still available on his site (I’m sure you can find the link). The completely straight-faced narrative features a young girl whose D&D habit leads to casting actual spells and a friend’s suicide.

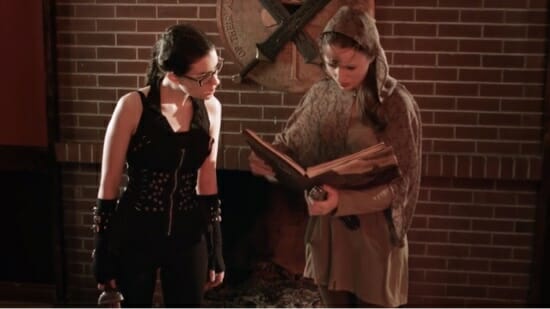

Chick’s work is deeply ironic. The comic itself became a beloved touchstone of mockery within the tabletop roleplaying community, so much so that in 2014, a group of independent filmmakers who have since produced a considerable body of work actually optioned the film rights from him and then made a 40-minute feature of it with some good production values and performances that treat the material exactly as seriously as it deserves. It is not entirely clear whether Chick, who died just two years later, knew he was getting lined up for a satirical skewering.

You can watch the result for free, and should. The actors are all game, spouting lines like “That’s the best RPGing I’ve seen in 15 years!” with straight faces. It’s simultaneously a great send-up of the moral panic and its death knell. The first episode of Critical Role, the YouTube series where prominent voice actors play D&D for an audience of millions, debuted the following year.

There are people who will look at the current criticism of D&D and then point to this earlier moral panic, frothing at the mouth about how the new generation of “woke-scolds” are ruining the game with “virtue signalling” and how this is all somehow exactly like Chick and the moral panic of the ’80s.

It isn’t, though, for the simple reason that the people criticizing tabletop games like D&D for their issues of representation and entrenched biases are arguing from the position that tabletop roleplaying is fun and more people should feel welcome playing it. That’s the sort of argument a fandom has with itself for its own good.

Kenneth Lowe has a Charisma of 7, you couldn’t have done much better than that! You can follow him on Twitter and read more at his blog.