The Rear Window Board Game Can’t Live Up to the Hitchcock Masterpiece

All images courtesy of Funko Games Games Reviews

Rear Window is among the very best films from one of the very best directors in film history, Alfred Hitchcock, who was a master at crafting absorbing, layered thrillers from scant premises—such as, what if a photojournalist broke his leg and couldn’t leave his apartment, but while basically spying on his neighbors from his wheelchair, he thinks he sees one of them commit murder? You don’t know if the neighbor (played by Raymond Burr) actually killed his wife or if the journalist (Jimmy Stewart) misinterpreted what he saw, until very close to the end of the film. (Side note: Ross Bagdasarian, the creator of Alvin and the Chipmunks and the original voice of David Seville, plays the neighbor who is a songwriter.)

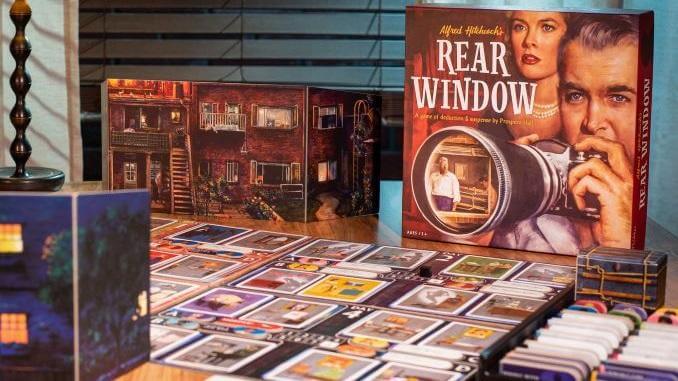

Funko Games has turned a number of film and TV properties into board games, including the Ted Lasso party game (light, and not that thematic, but it’s fun for a timed color-matching game) and the Jurassic World: The Legacy of Isla Nublar cooperative legacy game. They also brought Rear Window to the tabletop, using images of the actors from the film while trying to recreate the feel of the film’s core mystery—was there a murder, and if so, who did it—but the core mechanic of the game involves way too much wild guessing rather than relying on logic or deduction to get to the solution.

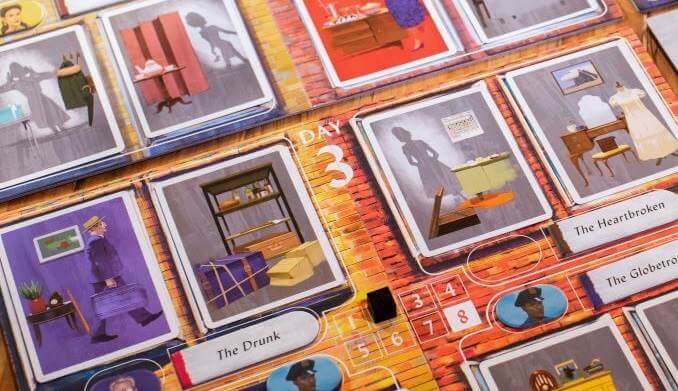

One player has to serve as the game master, while two to four other players will try to figure out which people live in the four apartments they can see, what their jobs or roles are, and if one of them was a murderer. The game master chooses the neighbors and their roles randomly from the set provided with the game (eight characters, 20 roles), hiding the solution behind their screen. In each of the game’s four days (rounds), the game master draws a hand of eight cards and plays two to each of the four apartments on the players’ board for that day. Cards have various elements that may include one of the possible neighbors, hobbies, clothes, furniture, decorations, and so on, and the idea is that the game master will put cards that have at least one element that matches something on that apartment. They may also place a card face-down if they think it doesn’t match anything in any of the four apartments.

After all eight cards are on the board, the players must try to guess the four neighbors’ identities and roles. The game master then says how many of the eight guesses are right, but not which ones. If at any point the players get all eight correct, everybody wins. If there’s a murder, however, the game master wants to mislead the players on just that one topic, winning by themselves if the players guess six or seven things correctly but don’t guess who committed the murder. If the players get all eight things right including the murder, they win and the game master loses.

The players have four one-use tokens that correspond to four characters of the movie that give them some kind of bonus information, such as pointing to a guess from a previous round and asking the game master if it was correct, or asking the game master to say what element on a specific card was the salient one. The game master also has three tokens that let them discard as many cards from their hand as they want and draw back up to eight.

The core problem with Rear Window is the core conceit of the game: Players are supposed to look at these cards and figure out the element that matters on each one while ignoring the rest, but the cards are so diverse that there’s too much noise and not enough signal, with more cards often adding confusion to the mix rather than making it clearer. If you’ve played Mysterium, you probably have the basic idea, although the cards in that game were far more abstract than the cards in Rear Window. If anything, Rear Window is more frustrating, because the cards often have the exact item/person you want to evoke in the players’ minds, but all the other stuff on them points away from it.

The fact that the game master can’t tell players more information about what they got right among each day’s guesses only exacerbates the problem. A raw number from 0 to 8 isn’t helpful—well, 8 would be helpful, but even 7 just tells the players one is wrong without any further indication—and there’s no other mechanism to narrow that down except for the players’ single token that lets them ask whether one specific guess was right.

If you liked Mysterium or similar games (Shadows: Amsterdam, Obscurio) that involve this sort of guesswork in the guise of deduction, you may love Rear Window. It looks great, which is even important given what a table hog it becomes after all four day boards are in play, and the components are good quality. I just think a deduction game should have more actual deduction, where you understand what’s been eliminated and can use logic to move forward to make better guesses.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.