When Living Colour’s “Cult of Personality” exploded on MTV in 1988, it became an example of how much had apparently changed since the network dropped its unofficial “color bar” by playing Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” in 1983. It was equally easy to view Living Colour as an anomaly—a black rock band who, with Mick Jagger’s help (he produced demos for the group and guested on their debut), managed to catch a break.

The story wasn’t so simple. Neither MTV nor the music industry as a whole had moved very far in terms of racial pigeonholing; black artists who didn’t fit into the industry’s stereotypical “black” categories—i.e., R&B and rap—found it nearly impossible to get in the door, much less get a deal, with record labels. Black audiences don’t listen to rock, went the refrain, and white audiences don’t want to see a black rock band. Perhaps these circumstances make the “Jagger as white patron” story line more believable, but Living Colour came to the singer’s attention partly because the band got a push from the folks who formed the Black Rock Coalition.

That’s only one point Maureen Mahon makes in her excellent Right to Rock. But while Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid helped organize and is still the best-known member of the BRC, Mahon doesn’t make the band her book’s focus. Rather, she approaches the BRC not as a music writer but as an anthropologist (she currently teaches in the African-American Studies Program at UCLA), investigating what it means to view music both as an expression of racial identity and an assertion against narrow-identity politics.

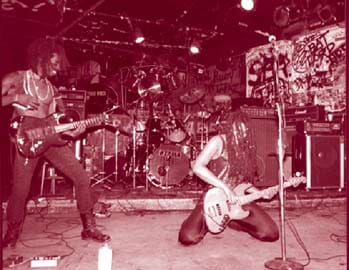

As she tells it, the BRC first came together in 1985 as a loose cooperative of musicians and fans in downtown NYC, spearheaded by Reid, producer Konda Mason and journalist Greg Tate. If the BRC had anything like a manifesto, it was Tate’s 1986 Village Voice essay “Cult-Nats Meet Freaky Deke.” “The point is that the present generation of black artists is cross-breeding aesthetic references like nobody is even talking about yet,” Tate wrote. “And while they may be marginal to the black experience as it’s expressed in rap, Jet and The Cosby Show, they’re not all mixed up over who they are and where they come from.”

For the most part, BRC members were middle-class, college-educated twenty- and thirty-somethings who grew up listening to the entire spectrum of American popular music and integrated it all into their music. The frustration came when labels and club owners resisted those synthetic sounds by claiming they “weren’t black enough.” BRC artists often addressed those concerns directly in their music, like Civil Rite’s “Corporate Dick” and “Black Assid,” with its telling refrain, “I’ve done nothing wrong / I put my heart into my song / And hear what you say / Just like Frank / I’m gonna do it my way.” We may be black, but we can claim Sinatra, too—not just James Brown, George Clinton and Jimi Hendrix.

And, as Right to Rock concludes with a chapter taking its name not from Hendrix but from Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks,” as long it’s still considered “idiosyncratic” for a black band to sound like Living Colour (or, for that matter, Mos Def’s rocked-up side project, Black Jack Johnson) we still need groups like the Black Rock Coalition.