On Friday, June 8, 2011, an all-black crowd gathered at Atlanta’s Cyclorama, a Civil War museum devoted to the memory of the Battle of Atlanta. We came to hear scholar-turned-novelist Dolen Perkins-Valdez impart her vital historical perspective on American life in the 245 years during which the institution of Southern slavery provided the country’s economic fuel, roughly from 1619 to 1864. The juxtaposition of faces of color against a living monument to the war fought over the issue of our ancestors’ bondage surely serves as a sign of the times. Progress doesn’t come without its own complications.

At one point during her talk, Perkins-Valdez told the audience, “I always encourage [black artists] to write, write, write, because I don’t want to be the only one telling the story.“

Tayari Jones would agree. “We’re all writing so many different stories. All of our voices together make a tapestry. Any one story is not complete,” she told me in an interview. Jones’ perspective aligns with that of many who see the African-American experience as a collective story we weave, a representation of the individual and collective wills that have continued to boldly assert humanity in the face of multi-generational traumas.

Jones’ first two novels—Leaving Atlanta, a book that took up where her predecessor Toni Cade Bambara left off in a literary treatment of the Atlanta Child Murders in a posthumous novel, and The Untelling, also set in Atlanta—couldn’t have been written in any time but our own. They rise from the author’s distinct positioning among Atlanta’s black middle class—a group that has been present and vocal since the founding of the Atlanta University Center’s colleges during Reconstruction, but never so large or so powerful as in the past 40 years.

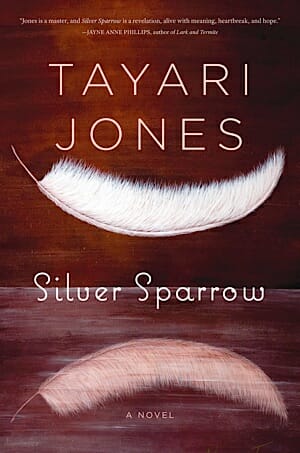

Taken as such, Silver Sparrow, Jones’s third novel, often offers interesting revelations about Atlanta, where the novel emerges and where its author was raised. It gives a compelling glimpse into all that has changed in Atlanta and in the world, and all that Atlanta’s changes represent for real people.

If this book spoke aloud it would speak with a quiet, unsteady voice, one on the edge of tears. Do not look here for a novel whose beauty will overwhelm you. Silver Sparrow rarely evokes wonder or awe. It’s like its narrators, sisters Dana and Chaurisse, each of whom sees herself as ordinary, not due much notice. Each envies those they call “Silver”—the shiny, beautiful, wanted people. Each views her world with a quiet, honest eye.

The book’s prose can feel lukewarm, and the story as a whole suffers at times from a surface treatment of complicated emotions. The book heavily relies on the conceit that an illegitimate daughter, Dana, is more attractive than her sister, Chaurisse, the legitimate daughter of their father James Witherspoon. It often feels like a fairytale oversimplification of an issue that, handled with nuance, might be a great theme.

Most of the book takes place during the 1980s. Teenagers, born a few months apart, the two narrators speak with the naivety and wisdom of children forced to confront adulthood, and engaged in the necessary act of constructing adult selves around their vulnerabilities.

Dana lives with her mother Gwen, the woman James married illegally in a ceremony across the state line in Alabama. Chaurisse lives with James and his legitimate wife, Laverne. James’s family in the shadows know all about the existence of his legitimate family, and find themselves forced to constantly compromise their own desires to keep James’s secret. If Laverne knows that James has another wife, she never admits it. Chaurisse grows up an only child.

Despite its failings, Silver Sparrow’s relationships between characters—and the calculations and negotiations each makes in the search for love, acceptance, and family—feel mostly real. James’ continued willingness to deny Dana as his daughter in the open—exemplified by a scene in which he is unable to protect her from a boy who will break her heart—breaks the reader’s heart too. The narrative sporadically demonstrates an ability to hook the reader by the heart and pull us into its world.

In interview, Tayari Jones identifies her books with the work of Anne Tyler and Mary Gaitskill. Jones’ own work also clearly exists in the arena that has been forged by writers like Terri McMillan and Pearl Cleage—writers who demonstrated, simply by telling the stories that mattered to them, that the 20th-century black middle-class experience is worthy of the novel’s form … and millions of American readers of all backgrounds support work that portrays it.

Jones also cites her admiration for the work of Toni Morrison. Silver Sparrow‘s offerings, though, are a far cry from the thematic richness, linguistic invention, and unforgettable character development that we find in even the briefest excerpt of Morrison’s work. But of course Morrison sets a high bar, one that few other living writers in the English language can match.

Don’t expect Jones’ work to do so. She writes works of popular fiction for a popular audience. This book’s emotional arc balances, and it can satisfy a reader looking for a heartfelt portrayal of human beings tangled up in the implications of one man’s bigamy. In fact much positive public feedback around the book expresses appreciation for this writer’s treatment of a common situation spoken about all too rarely in polite society.

But for readers who look for novels with language and ideas that push the bounds of possibility, or with images that resonate in the mind days after the back cover has been closed, this one may disappoint. The story is a simple one, simply told, but it’s crippled by its aspiration to be more. It reaches but does not grasp.

Given Silver Sparrow’s themes and its treatments, this novel, had it been written by a white woman, would easily be categorized as “women’s lit.” Sadly, that’s a fatal category for serious writers, a dead-letter office where books by female authors—works well-crafted and mediocre alike—go to final rest. Perhaps it’s only that the strength of the black female canon in American literature—a legacy stretching back to the work of Phillis Weatley and including Harriet Jacobs and Hannah Crafts in the 19th century, Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larsen, and Ann Petry in the first half of the 20th, and most recently Pulitzer-prize winner Alice Walker and Nobel Laureate Morrison—has suddenly inspired a frantic search for the next great black hope to fill those lauded shoes. Whatever the cause, we have burdened Tayari Jones with a great deal of our longing.

The Root spoke for many when it recently declared that Jones is “it.” But I ask whether such phrasing can apply to any American writer of any background nowadays. Witness the outcry over Jonathan Franzen’s recent designation as Great American Novelist by Time, to the continued exclusion of writers situated elsewhere along lines of race, class, and gender. It doesn’t take long after walking into a big-box book store to perceive that modern publishing stands as an enduring bastion of Jim Crow. Why? Separate but ostensibly equal, fiction by African-Americans sits on shelves far away from books by other-color writers. Are American reading audiences still so segregated that the American mainstream media choose their own messiahs—for reasons that might cause skepticism in any honestly probing mind—while with equally suspicious rationale, the African-American media choose their own?

“Black writers have always written everything. Writers have always been free to write,” Tayari Jones told me when interviewed, “The difference is that now black writers are viewed as individuals, rather than merely representatives of their race.” The change has come from the outside rather than the inside: “The way that we’re read has changed more than the way that we’ve written.”

She’s right. But it’s not only the way black writers are read by the public that has changed—it’s how they are presented to the public in the first place, and whether they’re presented at all. There have been times when no work short of genius could be published by an African-American author in the mainstream American marketplace. Nowadays ordinary books, books that do their work without much fuss, have an equal chance of finding wide readership. Enter Silver Sparrow.

Race has not become insignificant, but what it signifies is certainly changing. Atlanta illustrates that in countless, complex ways, and Perkins-Valdez’s talk at the Cyclorama was only one of them. At one point in Silver Sparrow one the characters, a transfer student to Mays High School says, “Where I’m from, everything is mixed. In Atlanta, at least where we stay at, everything is so black that y’all don’t know what it feels like to be black.”

When interviewed Jones explained that growing up in a black world, as she did, means that one doesn’t always know what it means to encounter racism in day-to-day life. “I grew up in an environment where people didn’t do things because they were black, but because they were human.” She asks that we see her characters, and the choices they make, in the same way. “The fact that they’re black isn’t irrelevant,” she said, “but it’s not as relevant as the question of their humanity.”

Silver Sparrow asks to be read for its own sake. It asks to be read in a world where black American writers of high literature, low literature, or anything in between can find readers—or perhaps even in a world where those designations now mean something different. This book may not stand out as a game-changer, but it well illustrates a changing game. Perhaps more of the author’s success can be attributed to her media savvy in the digital age, the hard work she has put into cultivating her image, and her dedicated support to independent bookstores across the country, than to the strength of her fiction. But it’s any writer’s right to tell an accessible story to an appreciative audience, and that is exactly what Jones has done.

Chantal James lives with her husband in Atlanta, where she is at work on her second novel. Follow her on Twitter @chantalalive, or visit her blog at theglobalsouth.wordpress.com