The publisher Doubleday has put the full weight of its marketing machine behind the release of Erin Morgenstern’s admirable debut novel, The Night Circus. Beginning with a Potter-esque buzz at this year’s Book Expo America, immense hype surrounded this book, one of a recent spate of high-profile novels about young magicians. Obviously, the big publishing houses hope to conjure some literary alchemy to fill the void left by Harry Potter, who (spoiler alert) vanquished Lord Voldemort … along with his own seven-book franchise… at the close of J.K. Rowling’s last novel.

The search for magical gold might be working. In August, Viking Adult released Lev Grossman’s The Magician King—a sequel to his 2009 novel, The Magicians. Grossman’s books follow a young magician and a band of angsty college-aged friends on their adventures in a magical land. The Magician King cracked the top 10 on the New York Times Best Sellers list.

Why, exactly, are book publishers—and audiences—boffo for all things magical and supernatural? Why this apparent magical-fantasy renaissance … and why now?

A quick answer lies in DNA. Human wiring brings along its appetites, and one of these happens to be a fascination with the unknown, with possibility beyond plausibility. It’s why we humans can fly now. It’s why our cities light up at night.

Deeper down, things that go bump in the night attract human curiosity, too. Has there ever been a culture without ghost stories or tales of supernatural beings … or without stories of good things and bad things beyond human control?

Still, the rise and mass appeal of the current magical-fantasy vogue, spearheaded by the Harry Potter franchise, might simply be attributable to timing more than anything else.

Rowling’s first volume, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, published in 1998. The film version flickered to life in theatres on November 16, 2001—a mere two months removed from the terror attacks that shook America. Is it possible that the story of good battling a shadowy enemy served as a more manageable proxy conflict for the American psyche? Did Harry Potter provide post-9/11 escapism?

Perhaps. We do have a precedent in fantasy literature published after World War II—notably C.S. Lewis’s The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe in 1950 and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring in 1954. These works, the left and right ventricles of the modern magical novel renaissance, made ultimate good versus ultimate evil the stakes in their plots, mirroring the fraught perceptions of WWII and the Cold War that lingered for the next four decades.

Whatever the reason, novels of magical possibility today bring publishers magical possibility. Some magic may trickle down onto good writers, as well.

The backstory of The Night Circus, for example, sounds like the stuff of publishing lore. An artist by trade, Morgenstern decided to write her first draft as part of National Novel Writing Month. (Each November, writers of all stripes all over creation challenge themselves to write a book of 50,000 words in a month.) The manuscript, rescued from an agent’s slush pile, eventually became the object of a six-figure bidding war.

Even before the book’s release, Summit Entertainment purchased film rights. (The studio had done a little bit of business with another supernatural franchise called Twilight. You’ve heard of it? In the first quarter of 2009, one of every seven books sold in the United States bore Twilight author Stephanie Meyer’s name.) Foreign rights to The Night Circus sold in advance in dozens of countries, and its first printing of 175,000 copies boggles the imagination in our tight-fisted age of publishing. The book currently sits comfortably at No. 2 on The New York Times Best Sellers fiction list.

There’s marketing and magic, but not a lot else in common between The Night Circus and Rowling’s boy wizard books or Meyer’s lite vampires. Morgenstern purposely eschews the cut-and-dried nature of the Potterverse, giving us flawed heroes and antagonists less evil than Lord Voldemort. She’s written a novel about magic with a core of realism.

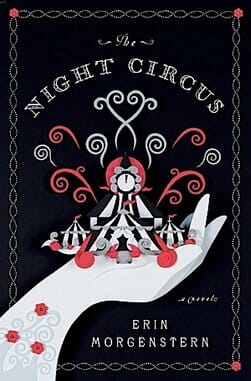

The hardcover edition of The Night Circus arrives with a gorgeous book design. The font and illustration on the jacket suggest the neo-art nouveau drawings of Edward Gorey, with Tim Burton’s added strangeness. Inside covers and a first few inner pages come in black and white stripe—hard on astigmatism, but a hypnotizing entrance for a magical novel. An opening passage connects physical book to magical world:

“The circus arrives without warning.

No announcements precede it, no paper notices on downtown posts and billboards, no mentions or advertisements in local newspapers. It is simply there, when yesterday it was not.

The towering tents are striped in white and black, no golds and crimsons to be seen. No color at all, save for the neighboring trees and the grass of the surrounding fields. Black-and-white stripes on grey sky; countless tents of varying shapes and sizes, with an elaborate wrought-iron fence encasing them in a colorless world. Even what little ground is visible from outside is black or white, painted or powdered, or treated with some other circus trick.

But it is not open for business. Not just yet.”

Soon, readers feel themselves pulled into Le Cirque des Rêves (the Circus of Dreams). It opens at nightfall, closes at dawn.

Set in the Victorian era, the book unspools a love story between star-crossed lovers, Celia and Marco, who have unknowingly been recruited and trained to play a dangerous game of nature versus nurture.

Celia’s magical skills manifested early. At age five, a caretaker delivered her to Hector, her father—better known by his stage name, Prospero the Enchanter. Celia came along with her mother’s suicide note pinned to her coat. In time, she tells Alexander, a figure who will turn out to be her father’s opponent in the story, “…My momma said I was the devil’s child.”

Under her father’s sometimes cruel tutelage, Celia learns to harness and control her substantial powers. She can shatter and destroy objects, then repair them perfectly. In one of her “lessons,” Celia’s father slices open her fingertips one by one with a pocketknife, then waits for her to stop crying and heal her own fingers, making the blood trail slowly reverse its course. Despite her impressive powers, Celia cannot fix living creatures as easily as inanimate objects. “Living things have different rules,” Prospero tells his daughter.

Her counterpart, Marco, comes from an orphanage. Alexander, the novel’s antagonist but also Hector’s co-conspirator, teaches Marco magical arts from ancient texts, but keeps his student isolated from society until he’s ready to compete in the game played in The Night Circus.

The game is dangerous … and a mystery. Their mentors never explain its barest rules to Celia and Marco, but they (and readers) soon surmise it’s a game akin to chess, with each player taking turns to outdo the other’s magic.

Hector and Alexander also purposely keep their students in the dark about the endgame—only one magician can survive.

Marco fires the first volley, in the form of a wondrous bonfire. Celia senses that the game has begun in earnest.

“She is still unsure who her opponent is, but whatever move has just been made, it has rattled her.

She feels the entirety of the circus radiating around her, as though a net has been thrown over it, trapping everything within the iron fence, fluttering like a butterfly.

She wonders how she is supposed to retaliate.”

Under the magical big-top, Celia and Marco create wondrous displays of magical one-upmanship: an ice garden that never melts, a maze of clouds, a living carousel. Eventually, the two youngsters meet—halfway through the book—and begin collaborating, building on each other’s works, falling in love during the process.

Their affair definitely violates the game’s unspoken rules.

The blossoming of affection between the lovers-competitors at a point so far along in the book underscores the attention to detail Morgenstern takes beforehand with her dream-like circus. A host of sideshow characters and subplots intricately weave in and out of Celia’s and Marco’s game. Sometimes the sheer number of characters prevents Morgenstern from fully fleshing out enough of them.

One story arc focuses on Chandresh Christophe Lêfevre. He assembles the people who create and perform in the circus, among them a Tarot card reader, young clairvoyant twins and the mysterious contortionist. Another story line reveals the people who become enamored with the circus and its wonders: Bailey, a Massachusetts farm boy, and Frederick Thiessen, a German clockmaker who creates a society of reveurs, groupies who track and attend the circus in far-flung places around the globe.

All unknowingly serve as pawns in the magical game … sometimes facing dark consequences.

The book’s plot and theme depend a great deal on time and timing, so tquite a bit of time-shifting and bending goes on in The Night Circus. Morgenstern also plays with narrative and perspective – don’t be surprised if you need to page back for dates, ages, locations and names at the beginnings of chapters. (Thank goodness chapters run relatively short.)

Morgenstern studied theater and studio art as a student at Smith College. That training as a visual artist serves her stagecraft here, supporting the otherworldly, fantastical circus tents of her prose. You’ll find much borrowed from the Bard, references or homages to Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest and Hamlet. Here’s how she describes Marco’s creation of a darkened forest of poem-covered trees for Celia:

“The striped canvas sides of the tent stiffen, the soft surface hardening as the fabric changes to paper. Words appear over the walls, typeset letters overlapping handwritten text. Celia can make out snatches of Shakespearean sonnets and fragments to hymns to Greek goddesses as the poetry fills the tent. It covers the walls and the ceiling and spreads out over the floor.

And then the tent begins to open, the paper folding and tearing. The black stripes stretch out into the empty space as their white counterparts brighten, reaching upward and breaking apart into branches.”

If Morgenstern’s attention to detail (and beautiful language) sometimes slows the pacing of her book, her circus is still a place of origami wonder and mystery that deserves unfolding with care. In some ways, the circus becomes the book’s main character; the author creates a living, breathing ecosystem that overshadows Celia and Marco, and their love story. (Morgenstern spends a bit less talent on nurturing the development of that relationship. The magicians meet only a few times before—presto, change-o—they’re bewitched, bothered and bewildered.)

If the first three-quarters of the book meanders languidly, the final section hurtles toward a climax. Can Celia, Marco and the circus all survive the game to which they’ve been bound?

Well … how can we be sure? The resolution proves a bit confounding, even with re-readings. The happily-ever-after doesn’t appear to be quite what it seems, but maybe that’s Morgenstern’s point: Living in gray, somewhere between all those black and white stripes, blends our worlds—magical and not.

Christine N. Ziemba is an arts and culture writer based in the non-magical suburbs of Los Angeles.