First, a word on the title: Percival Everett by Virgil Russell is a book by, that’s right, Percival Everett.

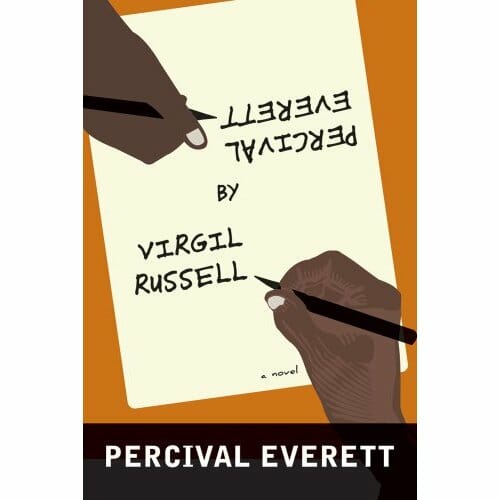

Possessed by a loopy, madcap energy that drives it, the novel literally loops back on itself, stories within stories. A pair of Escher-inspired hands on the book’s cover appear to draw the title, hinting at structure(s) employed within. You may immediately be thinking “Oh no … not another self-referential, experimental, metafictional novel with the author as a ‘character.’”

You needn’t worry. Percival Everett refers to itself, but also far more.

Everett’s latest (he’s the author of more than 20 books) again demonstrates that a literary work can be cerebral, emotionally affecting and highly readable at the same time. The novel also turns out to be relentlessly funny.

An example: The (ostensible) narrator asks his father (a writer) what most irked him about his career. He replies:

“Son, it was being called a postmodernist. I don’t even know what the fuck that is! Some asshole tried to explain it to me once, said that my work was about itself and process and not about objective reality and life in the world … After I told him to fuck himself and the horse he rode in on, I asked him what he thought objective reality was.”

Percival Everett itself poses questions about what objective reality is, or whether it exists at all.

The novel begins with a son visiting his father in a nursing home. The father presents his son with a piece of writing, claiming the son would have written it “if [he] were a fiction writer.” To complicate matters, the text eventually suggests that the first-person narration we encounter has the son as its source—a son who imagines his father imagining what his son would write. These shifts, of course, leave the reader uncertain: Is the son or the father narrating? Later, the narration shifts to historical figures (including Nat Turner).

After “objective reality” has been destabilized, it becomes clear that the point of view doesn’t actually matter, or it matters less than the story. Percival Everett sets up multiple (potential) narrative layers, but in practice the reader cuts through them. “I’m an old man or his son writing an old man writing his son writing an old man. But none of this matters and it wouldn’t matter if it did matter.”

So what’s this story? A central plotline involves the struggle of the father and his fellow nursing home residents against comical, bumbling orderlies. The staff also happen to be incredibly cruel.

When the narrator describes orderlies stealing from the elderly, or pushing an old man to the floor, we forget issues of point-of-view. Similarly, when presented with a multipage list cataloging the various tics and character traits of orderlies Harley, Tommy, Cletus, Leon, Ramona and Billy, we’re entertained and engaged, or at least morbidly curious.

This sketch list comes as one example of multiple structural forms used to organize text. We find three longer sections, titled “Hesperus,” “Phosphorous” and “Venus.” Those familiar with Gottlob Frege (cf. “I’m afrege this is true,” on page 142) will recognize these planetary bodies as one and the same. (The first two were names in the ancient world for the appearance of Venus in the evening and morning, respectively.)

Each of the three sections contains chapters with headings like “So Wide a River of Speech,” “Is Semantics Possible” and “Ontology and Anguish.” These erudite titles further showcase the work’s concern with classical problems found in the philosophy of language—problems like the impossibility of true communication. We find the Phosphorous section divided into two “chapters” and 48 numbered sections, these consisting of poetry, lists, a letter, a reference to the Banach-Tarski paradox (“A pea can be chopped up and reassembled into the sun.”) and a preface: “I don’t know if readers will like your novel…”

So where does all this take us? As a text, Percival Everett stands on its own, to be sure, but also deftly incorporates stream-of-consciousness techniques and references to both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake in the form of neologisms, compound nouns, insertion of foreign languages, und so weiter.

Consider: “…the beautifulest of all visible things the lightning strikes of summer the stars the nebulae the nebulæ for only etymology’s sake some sea tempest.” Or: “…because it was time you had given me, time that just twiddled and peetled and staggered and tripped into the gloaming of everydayness.” Just as Finnegans Wake features a 101-letter word and nine 100-letter words, Percival Everett contains an even longer coinage suggestive of a “bus crash.” The word runs for five lines:

“Shibocraishcrunccruncsqirpopchiksanpcunkicripfissssclnterterchi-

chinkripdanfripbingchinriplashicrackripchikpoptapknicknocslith-

ingkascrippopsicbangabingafrangakripknitficrashshebinbangboo-

mbinggingfeshcaripcrazingfacrinkacrashcringsnapsnasnasnasna-

ppingcrumkarumvfuvfuvfuvfuvfuchinkfuck”

Despite these nods, Percival Everett moves beyond Joycean, or anything-ean. Its focus is both simple and incredibly complex. Simply put, how does the identity of the teller affect the tale? Everett seamlessly incorporates philosophy and theory, while also enjoyably skewering both. And once the reader has worked through those levels, compelling stories remain.

The “preface” near the end of the novel aptly posits that the book “concludes, as perhaps all things conclude, appearing as little more than an attempt to discern how one can best find some happiness in this life.”

Brooks Sterritt is from North Carolina. His fiction appears or will appear in Denver Quarterly, LIT, TRNSFR, Web Conjunctions and elsewhere. He lives in Boston where he is at work on a novel.