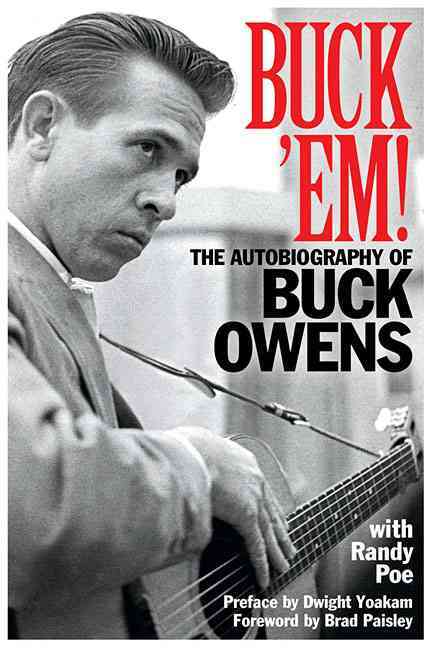

Buck ‘Em!: The Autobiography of Buck Owens by Randy Poe and Buck Owens

Acting Naturally

Books Reviews

Sometimes people get written out of history for strange reasons. It happened to the country singer Buck Owens.

Owens deserves attention. He had 21 No. 1 country hits and defined the Bakersville (California) country sound in its early years. He acted like a country music outlaw—outspoken in his resistance to the domination of Nashville—well before Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings made it cool (and made money from it). Owens also worked in TV and radio, expanding his brand and cross-promoting back when establishing one’s self as musician-and-mogul didn’t occur to most performers as a standard goal.

Despite all this, Owens doesn’t get the respect he deserves outside of the country community. (Country singers have a better idea of what’s going on: before this book gets started, both Brad Paisley and Dwight Yoakam sing Owens’s praises.) Guys like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson have great music, but they’ve also got culture-wide cachet: Cash has the black-clad image, the Bob Dylan duet, the albums produced by Rick Rubin—all signifiers of a certain level of hip acceptance. Nelson’s got his laid-back hippie vibe, the “Outlaw” stamp on his forehead, the million-selling albums. Owens? We know him mainly as the guy who originally recorded “Act Naturally,” which the Beatles covered on their Help album.

Owens died in 2008, but author Randy Poe, who has also written books on Duane Allman and blues lyrics, managed to transform numerous taped conversations with Owens into Buck ‘Em. It’s a humorous, easy-going book with a conversational tone. Still, underneath Owens’ commitment to describing his life, we find strength of purpose, a feeling that he wishes to correct a long-standing attention deficit.

Some discounted Owens early in life. One woman in particular didn’t think he had a bright future as a vocalist. When young Owens tried to sing that tricky ballad, “Happy Birthday,” to a Mrs. Wallace, she quickly stopped him and offered some career advice: “Son, whatever you do, don’t ever try to have a career as a singer.”

But Owens loved music, and he played guitar constantly, even in difficult circumstances. One night he “learned one of the main rules about playing in rowdy honky-tonks: If a fight breaks out, don’t stop playing—just start playing louder.” Presumably to Mrs. Wallace’s chagrin, Owens eventually started to sing as well.

He worked as a radio DJ during the day, plugging the gigs that he played at night. His guitar work earned him notice, and he managed to land the lead guitar role on some recordings for Capitol records in September 1953. Even then, he didn’t have a hit of his own until March of 1959, at 29 years of age, when “2nd Fiddle” cracked the top 25 (country charts).

The first No. 1 country hit came in 1963, and then they kept coming regularly, for close to 10 years. In 1964, Owens released a remarkable single: the A side, “My Heart Skips A Beat,” worked its way up to No. 1, only to be knocked off by the B side, “Together Again.” Then the A side decided to get popular again, reclaiming the top spot. (“The first and only time that both sides of a country single” topped the charts.) Owens carefully notes that this historical moment took place “a long way from Nashville.”

Owens has plenty of similar feathers in his cap. For those who believe in the power of first-take recordings and preserving mistakes with the magic…that’s Owens’ way of life.

“I’ve always written songs that were intentionally simple,” he said. “I couldn’t sit down and manufacture a song…a good song has always come fast.”

People often praise the fast and loose setup at, for example, Stax records in Memphis, which captured spontaneous eruptions of emotion and creativity. Here Otis Redding once legendarily recorded his Otis Blue album, 11 songs, in a day and a night. Owens rolls at a similar pace. “We did two four-hour sessions in two days, and came away with 10 songs,” he says of the album Before You Go. And “we didn’t rehearse at all.”

Owens’s attitude also captures the essence of rebelliousness. He recorded an album of Christmas songs…in June and July. He had the gall to cover a Chuck Berry track, infuriating some of his fan base. Owens shrugs off their anger, noting that he “always thought Chuck Berry was a great songwriter…never heard a song of his that wasn’t one of those good ol’ story songs.”

Just to make sure the Nashville country establishment knew Owens didn’t give a damn about their opinion, he “took out a full-page ad in this Nashville trade paper called the Music City News,” telling them to back off.

In fact, every part of Owens’ career seems fit for critical embrace. He regularly played 300 shows a year—a brag-worthy number that used to appear regularly in descriptions of the hip-hop band (and critical darlings) The Roots. Years before Willie Nelson got to pick his own sound, Owens fought his label for increasing control of his music, getting rid of the strings and backup singers the label wanted to slather around his voice.

So the question: Why don’t we hear Owens consistently mentioned in the same conversations as his peers, the Cashes and Nelsons?

Maybe it’s due to Hee Haw, the TV show he got paid handsomely to host—a rural-themed “comedy…corny as hell.” Although “the music was definitely worth tuning in for,” “if you were one of the tens of millions of people watching me on TV, you saw a guy who looked like a country bumpkin, wearing his overalls backward…how do you take that guy seriously?”

The critical establishment and the non-country audience started to write Owens off after seeing those overalls.

David Cantwell’s recent book about Merle Haggard, Merle Haggard: The Running Kind, suggests that a similar thing happened to Haggard after he recorded “Okie From Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side Of Me.” These songs became anthems for the right wing as it came back into power at the end of the ‘60s, prompting one critic to draw comparisons between Haggard and Spiro Agnew.

Owens surely doesn’t represent the only singer who got caught in cultural crossfire, but his reputation suffered more than Haggard’s. Pop culture and politics interact, and political wars play out in listening patterns and criticism. This still holds true with country music, which some people shallowly dismiss simply because it’s a product of a culture they don’t understand.

Dislike Owens’s overalls? Buck ‘Em suggests an alternative: Enjoy his music.

Elias Leight’s writing about books and music has appeared in Paste, The Atlantic, Splice Today, and Popmatters. He comes from Northampton, Massachusetts, and can be found at signothetimesblog.