As I sat—nay, lay—reading The Southerner’s Handbook: A Guide to Living The Good Life by the editors of Garden & Gun magazine, my mind danced back to my grandmother’s house in the town of Climax, Ga., where I spent a lot of time as a kid in the ’60s and ’70s.

Nanny’s house had a wrap-around front porch with rocking chairs and a yard overgrown with palmettos and the occasional pomegranate tree. She made delicious fried chicken and potato salad (from tubers she dug herself and sent me to fetch from underneath the back porch, where she stored them). She drove a little beige Plymouth with fishing-pole holders attached to the roof and loved nothing more than to pick catalpa worms off a tree in her backyard and decamp for an afternoon of bream-fishing and gnat-swatting at a nearby pond.

She may have been the only daughter of a country gentleman with a passel of boys and enough land to leave each of his children his own farm. But there was not a particle of pretentiousness in her playful heart.

Not a lot of books in her house, either.

I remember a Bible and a few tattered cookbooks. I also have a vague recollection of a strange instructional manual—from the ’30s or ’40s, I’d guess—filled with rules of etiquette, decorating advice, fashion tips and recipes. The book had an arch tone and a vulgar smugness, as if it were written for glove and hat-wearing ladies who smoked cigarettes and put on airs. Definitely not Nanny’s crowd. No wonder she never looked at that thing.

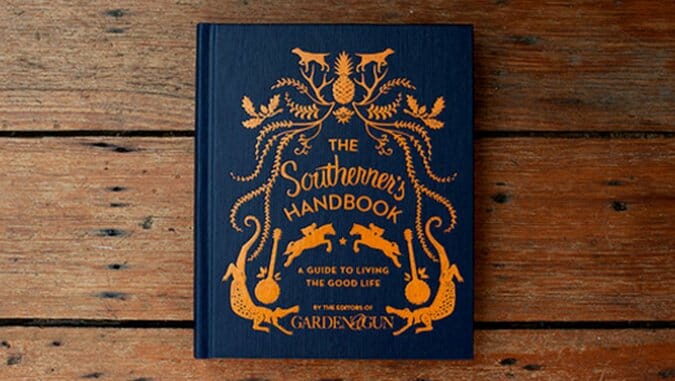

This brings us back to the volume at hand, The Southerner’s Handbook. Bound in navy and spangled with etchings of dogs, pineapples, alligators, banjoes and derby horses, the prim little Garden & Gun publication is a romantic nod to the sort of authentic how-to guide you might mistake for treasure, if you chanced upon it at a vintage bookstore or in the bottom of your grandmother’s dresser drawer, under the Chantilly dusting powder.

It’s a sneaky, self-important, Yankee-friendly little poseur of a book that beguiles you in its smart-alecky way—with its grand pronouncements and end-all, be-all prescriptives on how to fold pockets squares and collect decoys.

Especially if you are a non-Southerner looking for an insider’s guide to the finer points of bourbon, barbecue, birddogs and the blues—written by an A-list stable of arbiters like John T. Edge and Julia Reed—it’s the eel’s ankles.

You need it like you need your Billy Reid quail jacket and your bottle of Pappy Van Winkle. (And yes, you can be certain that both the Florence, Ala., fashion designer and the scion of the famous Van Winkle whiskey clan appear in these pages as experts.)

Anyone born South of the Mason-Dixon line, however, is probably not lacking in recipes for deviled eggs and pecan pie. You’ll find recipes for both here nonetheless, along with instructions for many pursuits that any Southerner worth his Case pocketknife will have mastered long ago: frying fish, making lemonade, boiling peanuts. (Can’t wait to see the response of my brother, a South Georgia peanut farmer and fish cook par excellence, when I tell him the secret ingredient for fish batter is club soda.)

You just go right ahead and send out for mail-order stone-ground hominy. I’ll stick to my Aunt Jemima grits stirred with a dollop of butter and cream cheese.

That said, perhaps I would be better served to savor than sulk.

Indeed, there are pearls of wisdom scattered among the handbook’s more obvious reflections. The oyster-shucking tutorial is a keeper, and I’m dog-earing New Orleans doyenne Leah Chase’s step-by-step for making a proper Creole roux.

The Southerner’s Handbook—which is divided into chapters on Food, Style, Drink, Sporting & Adventure, Home & Garden, Arts & Culture—really takes off with the essay by the Mississippi-born Reed that opens the Style section. Here she is describing her “first ever summer in the Hamptons:”

I was told by the formidable wife of an editor friend that under no circumstances could I serve the pot of seafood gumbo and platters of fried chicken and potato salad I’d planned on having at my debut gathering. “That’s not we do here,” she said, instructing me instead to have a seated supper of plain grilled swordfish that was as ubiquitous that summer as shoe leather, and just as tasteless. I was slightly terrified, but I ignored her and I have never seen people so happy. By offering up an exotic (to them) antidote to the asceticism to which they’d unwittingly been subjected weekend after weekend, I set a tone I hadn’t even realized I was setting. They drank more and laughed louder, ate the chicken with their fingers, and stayed very, very late (except for the aforementioned arbiter who ostentatiously refused to eat a morsel and left her grateful husband behind when she drove home in a snit).

Don’t you just love that?

But Guy Martin’s introduction to the Sporting & Adventure chapter was equally on point. Here is Martin describing the magnificent bird and fish sanctuaries of the South: “From Curaçao to the Kentucky Bluegrass, the unruly mass of aquatic and terrestrial fertility—and the climates and microclimates that support it—is how the how-to-ness of the South came to be.”

Come again?

Flipping to Martin’s bio in the back of the book, I see that he “lives in New York City, Alabama, and Berlin, spending much of his time on the many different airplanes that fly between them.” Perhaps that’s how he acquired his bird’s-eye view of the landscape. (Earth to Martin, earth to Martin.)

For all its silly piffle on how to throw a rope, how to make tabby and how to wrestle an alligator, the handbook redeems itself with the words of Roy Blount, Jr., Allison Glock and Dominique Browning.

In Sipping Whiskey, Blount does just that, to delightful effect. You can just hear him getting tipsy (or at least pretending to) as he writes. Fascinated by whiskey bottles with corks, he describes the f-toong and the squeeoong noises they make as he removes the stopper:

I’ve pulled them so many times now tonight, trying to decide which one has the better tone, that they’ve lost their music. Kinda sad. I’ve worn them down. They are not tight anymore.

I am, though. Just to the point where I’m feeling sorry for corks and have forgotten what exactly I was researching. But I enjoyed it. Do I live near here?

Glock’s six-page treatise, Sweet Tea: A Love Story, is the best thing I have ever read on the subject and sure makes me crave a swig of her beloved brew from Knoxville’s Chintzy Rose café. “They could serve it out of their shoes and people would still line up to drink it,” Glock writes of the mysterious orange- and lemon-scented brew that she could never slurp enough of.

Browning captures childhood visits to her father’s family home in Kentucky with a somnambulist’s dreamy poetry. One night on the sleeping porch, she fell out of the big bed, became frightened and stepped into a pan of chocolate cake that had been cooling on the porch. “The next morning my grandmother had me lie down on a brown paper bag that had been cut open so that she could make a pattern of my body for a new dress—the house had a sewing room, which had the serene beauty of the purposeful.”

Sigh.

The handbook closes with meditations on the arts, including Ace Atkins’ riveting “The Truth About Robert Johnson and the Devil,” Ace Atkins and Angela Moore Atkins’ narrow foretaste of the divine glory that is Southern folk art and Hal Espen’s four-page summary of Southern literature (with nary a mention of the novels of Donna Tartt or a single play by Tennessee Williams, Horton Foote or Alfred Uhry).

In her opening essay on Southern Art, Glock, once again, gets it just right:

Thing is, when you come from the bayou or the holler or the fields, folks don’t expect much. They sure as hell don’t expect culture. And so began a long tradition of regional dismissal by outsiders. And a habit of distinguishing ourselves. Of course, being Southerners, we figured out a way to be heard anyway. We told stories

We told our stories with humor and vicious heart and volume. We sang about sex and called it rock and roll. We painted devils you could fall in love with. We wrote (and wrote and wrote) in feral tongues with unprecedented vulnerability and transparency, and in doing all this, we wiggled in and rearranged your insides and made you see us, the real us, because, above all, Southern art is not something you can hide from. It will make you look. And you will be forever changed as a result.

I get choked up reading that.

And as I lay in my grandpa’s bed turning the final pages of The Southern Handbook I found myself wondering what would happen if some Southern kid stumbled upon it 20 or 30 years from now—like I did with that weird women’s book at Nanny’s house.

Would he be inspired to make a didley bow, adopt a Boykin Spaniel or stir up a stiff Sazerac? Would Wilber’s Barbecue in Goldsboro, N.C., still be smoking whole hogs and making Brunswick stew? Would we still care about Edna Lewis and John Egerton?

A compendium of trivial arcana, useful information, helpful hints and (in a few cases) writing of exceptional merit, this Garden & Gun offering is a fascinating capsule of Southern culture in our time—the high and low, the timeless and the trendy, the stuff that matters and the stuff that, in the end, won’t really matter much at all.

Wendell Brock has covered Southern food and culture for more than a decade. A longtime editor and writer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, his work has appeared in virtually every major American newspaper, including The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times. As an expert on Southern food, his articles on pecans, peanuts, okra, and Edna Lewis have appeared in Saveur.