Be very glad Saul Austerlitz was the guy who had to sit through all 98 episodes of Gilligan’s Island and not you.

The author admits to this Sisyphean undertaking in his acknowledgments section, sardonically revealing that he completed the task in the presence of his unwitting newborn son (the poor kid). Indeed, Sitcom emerges as an exhaustive and deeply felt undertaking, but it also conjures up nightmarish visions of having to slog through a landfill’s worth of mediocre product just to dust off the jewels that may constitute an under-appreciated art form.

You’ll find Sitcom, as its very title suggests, is more of a survey course in television comedy history and its inextricable link to the socio-political movements of the culture that consumes it. As such, its raison d’être gets a little muddied by an introduction that takes up the torch of reclaiming a bastard stepchild genre as an “art form.” Everything can be considered an art form, of course, from plumbing to bread baking, but the book kicks off as an advocate for the bump in status, only to then abandon the soapbox and deliver essentially a (very well done) overview of a vast subject. By the author’s own admission, the sitcom “is a proxy; a substitute family, or substitute circle of confidantes” and a form whose history has often been about nothing more than “Americans gathering in unparalleled numbers to watch their favorite funny people.” Pretty no-nonsense stuff.

But is it art?

Yes, arguably, sometimes it is and often aspires to be. Taken alongside the Renaissance that TV dramas have enjoyed for the last decade, perhaps the time has come for at least some of the more innovative small-screen yuckfests to get their due. However, coming out of the gate with this premise can undercut the more palpable pleasures of this affectionate and incredibly thorough study. After all, while there might be some academic bickering about whether or not Curb Your Enthusiasm or How I Met Your Mother constitutes art, there would be very little argument as to what place Three’s Company or According to Jim hold in the pantheon.

Better to put these thorny issues aside and focus on the rich and varied history of the whole megillah—which is, essentially, what Sitcom sets out to do in the first place.

All great comedy represents, for certain, finely honed craft. And when we combine expertly crafted jokes with perfectly realized characters, we get the iconic shows that Austerlitz profiles here. His descriptions of hilarious moments and plotlines from such groundbreaking work as The Honeymooners, The Dick Van Dyke Show, All in the Family, The Cosby Show, Seinfeld and 30 Rock effortlessly carry you along on a wave of grins-while-reading and goodwill for the programs, even if you weren’t around when they originally broadcast.

Austerlitz picks a gimmick as a framing device for his presentation, but immediately transcends it with his no-stone-unturned approach. He divides his book into 24 chapters, each revolving around a single episode of a landmark show. What could have become a pretentious drilling-down into the minutia of comedy content very quickly reveals itself to be a mere jumping-off point. Austerlitz uses this clever conceit to veer onto nugget-filled tangents, citing further episodes of the show profiled in the chapter, and an often dizzying array of other programs it influenced, and in turn their importance in the cultural landscape.

He begins with I Love Lucy, smartly acknowledging the importance of the pre-TV format of radio, and even clues us in to how the uniform lighting style that came to dominate sitcoms began with … (drumroll please) … Desi Arnaz. Arnaz commissioned as his lighting director the same German cinematographer who shot Fritz Lang’s silent masterpiece Metropolis!

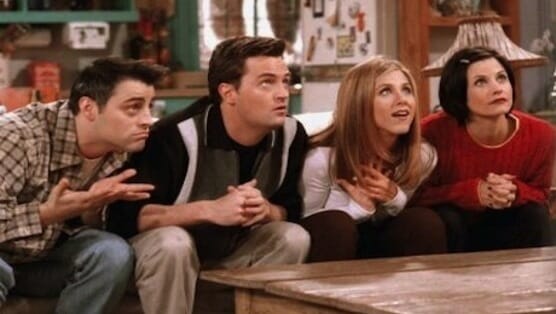

The chapter on The Simpsons makes a thought-provoking leap to Malcom in the Middle by way of South Park, in which Austerlitz beautifully describes Eric Cartman as “Bart [Simpson]’s untrammeled id.” The Taxi chapter floats the interesting idea that ensemble shows (Cheers, Seinfeld, Friends), having no central character, essentially chronicle a collection of nut ball sidekicks. And with Sex and the City, the show’s debt to its predecessor The Golden Girls seems perfectly well founded in Austerlitz’s vision.

Austerlitz uncovers, perhaps most impressively, the countless connective threads of the sitcom as a self-referential medium. From Lucy’s show business aspirations to the “show about nothing” to the meta-pop culture references of Freaks & Geeks and Community, Austerlitz nails TV comedy as storytelling constantly looping back on itself. Does this enhance or cheapen its reputation as an art form? The unspoken question hangs over proceedings.

Perhaps the most profound observation in Sitcom comes when Austerlitz tracks the rise of less artistic, crowd-pleasing fare like Mister Ed and My Mother the Car to the expansion of the reach of television itself:

We think of TV as coming into existence all at once in the late 1940s, but in truth, TV was rolled out in the United States in limited release. Having begun in cities like New York and Los Angeles, television only slowly made its way into the interior of the country. Rural areas were especially tardy in receiving access to TV signals. As television penetrated deeper into the less populated pockets of the country, the nature of viewership changed. Series such as The Phil Silvers Show were unlikely to appeal to this new, less sophisticated brand of television watchers….Creatively, the sitcom took a decided step backward, in large part because new audiences demanded a different kind of programming less given to artistic daring.

Austerlitz proves really good at pulling out priceless behind-the-scenes anecdotes that linger in the memory. Ed Asner storms back into his failed audition for Lou Grant on The Mary Tyler Moore Show and uses an obscenity-laced tirade to demand they let him try again. Bill Cosby explains why he was wary of going back into television: “I don’t want to see one more car moving sideways down the street for two blocks—passing a (white) hooker talking to a black pimp—before crashing into a building in front of a man who drops to his knees with a .357 Magnum.” Perhaps the most gut-busting side note in the book comes from the former Head Writer on season two of Roseanne, whose dust-ups with the volatile Ms. Barr resulted in him taking out an ad in Variety to say that he and his wife would be sharing “a vacation in the relative peace and quiet of Beirut.”

Readers will not agree with Austerlitz on everything. He adores M*A*S*H and The Simpsons, which will raise few objections. It seems rather shortsighted, however, to claim that the humor in All in the Family no longer feels watchable in a modern context. (In this reader’s opinion, the show’s conflicts, particularly in its early seasons, could easily be transposed to the political landscape of today.) Also, Austerlitz profiles Leave it to Beaver purely for its symbolic status as the signature sitcom of a whitewashed America, but one can view it as equally notable for its knowing and funny look at childhood logic and behavior.

Austerlitz writes with a direct and punchy style (one of my favorite turns of phrase came in his description of Bilko’s U.S. Army characters as a “stumblebum hodgepodge of malcontents”) that makes for compelling reading. On a small but shockingly noticeable note, the author drops in a few of his own random expletives in the normal course of authoritative discourse. They seem woefully out of place.

In the end, though, let’s not argue about whether the TV sitcom is an art form. Let’s just say some shows aspire to be, and might, on a subjective basis, get there at times. Once we establish this, we can review the sitcom’s place in the landscape of our lives with nostalgia, affection and a good portion of insightful (and not unfounded) sociological analysis.

Austerlitz delivers exactly this in his pleasantly satisfying, quite informative book. We do not need to ask any more of it.

James Napoli is an Assistant Professor in the MFA in Professional Screenwriting Program at National University and teaches Script Analysis and Motion Picture History at Columbia College, Hollywood. He is the author of the best-selling humor book The Official Dictionary of Sarcasm.