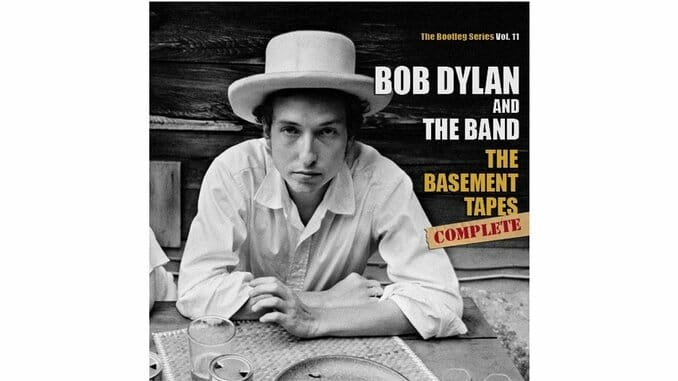

For music collectors of a certain age, the release of The Basement Tapes Complete has been a long time coming, and the opportunity to hear everything that Bob Dylan and his friends recorded at a rented house in upstate New York in 1967 is the realization of a decades-old dream. Advance press has touted the issuing of this six-CD set as having the significance of finding the Holy Grail or discovering the lost city of Atlantis. I’d settle for calling it the most significant musical event of the year, but I realize that people coming late to the party might wonder what all the fuss is about. In light of this, I’ve been trying to imagine what this music would sound like to someone who came upon it without any sense of context or cultural history.

Drop any of the six discs into a CD player, and you’ll be immediately overwhelmed by the hiss of the tape sound, the hollow mono and a pesky organ residing far too close to the microphone. On some tracks Dylan’s vocals are no more prominent than the tambourine or any of the other random instrumental sounds rising and falling in the mix. For all intents and purposes, much of what the musicians play sounds no more professional than what you would hear emanating from any number of basement jams taking place anywhere in the world. Of course, that’s part of the magic.

But, still, why do some of the songs suddenly end in the middle of a verse? Why can’t Dylan sing the same song the same way twice? And why devote six crammed CDs, two books and a heckuva lot of academic interpretation to these guys’ musical—and sometimes downright unmusical—ramblings from way back in 1967?

If you were around then, or have taken in any of the mythology from that time, you know that 1967 was supposed to be the summer of love. Psychedelic music was peaking, and The Beatles had just issued Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band. Cream was riding the top of the charts and Human Be-Ins popped up everywhere, encouraging people to “tune in, turn on and drop out.” At a time when rock musicians started spending six months in the studio to produce their “masterpieces,” complete with electronic effects, backwards-running tape and lyrics about peace, love, LSD and 1,000 armed Kalis, Bob Dylan and his pals (soon to be called “The Band”) were playing Hank Williams and A.P. Carter tunes in a basement with only sleeping dogs as witnesses. While Pink Floyd and The Grateful Dead were developing their light shows, Bob Dylan was typing off-the-cuff lyrics on an old typewriter and creating songs that anticipated the alt-country movement three decades before it happened.

The music on The Basement Tapes Complete is so simple and uncluttered that it was truly revolutionary when it was first heard. It’s impossible to sidestep the irony of the situation. By the time other musicians and the music-buying public had caught up with what Dylan was creating, and albums like Blonde on Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited encouraged all manner of psychedelic explorations, he’d lost interest. Dylan had brought his music full-circle by following his intuition and deciding to play and record without any intention other than to blow off steam and have a good time. Once again, he was ahead of the curve as he showed people what “dropping out” was really about. By 1967, the counterculture had been co-opted by the media and the corporations and had given way to consumerist symbols and beaded, peace-sign variations of conformity. So, when a reclusive singer and his bearded and scruffy cohorts started playing whatever came into their heads, they created a kind of archaic modernism that encapsulated all of American music’s past and hinted at a future that has never been replicated. Strident and tuneless? Breath-taking and beautiful? The music Bob Dylan and The Band recorded while the rest of the world went about its business was so prescient and expressed the spirit of independence and inquiry that the counterculture promised, yet so rarely delivered. This is music that was produced independently—years before such a thing was heard of—with no planned album or goal of any kind in mind. In this light, the true cultural significance of the Basement Tapes starts to sink in.

It’s been said that Bob Dylan had no choice but to dial it back. The motorcycle accident that sidelined him in the summer of 1966 couldn’t have come at a better time. Though his injuries may have been exaggerated, Bob Dylan was not healthy for a lot of other reasons when he was taken out by the accident. He’d been using huge amounts of “medicine” of all kinds to help him cope with a grueling touring and recording schedule that saw him release three albums in 1965 alone and play hundreds of concerts all over the world. In addition to that, at the time of the accident he was thinking of another album, completing a novel and planning a TV schedule. It was a completely unworkable situation that couldn’t continue, so even if the accident was an excuse, it was one that allowed Dylan to step off the wheel—so he could reinvent it.

The nearly 150 songs collected on The Basement Tapes Complete provide perhaps the greatest insight into an artist’s creative process that we’ve ever been allowed to share in. Whatever limitations one could cite with the finished product or the lack of polish in the performances, it’s important to realize that this music wasn’t recorded for us to hear. It was personal, about intuition and reacting on the fly. It’s not self-conscious in any way, and it forces us to reassess exactly what it is that we expect when we listen to a song.

The power of this off-the-cuff music is not found so much in the music itself as in what it intimates, the maps it draws and the potentials it suggests. Admittedly, these songs are definitely not for everyone. They’re raw, so raw that it’s virtually impossible to describe them in words—which isn’t to say that the songs are unremittingly loud. Many of them are rather soft and were recorded without a drummer (Levon Helm joined the band for some of the last sessions) but still they have an undercurrent that howls and shrieks like nothing I’ve ever heard before.

So, if this music was intended to be a private experiment, how is it that these tapes have become so legendary and sought after? Even though he’d been in an accident, Dylan had to justify his time off, so he told his manager that he’d tape the basement sessions and send around demos to see if any other artists wanted to record the new songs he was writing. At that time, there was no bootlegging industry, so the tapes were liberally distributed and it didn’t take long before someone liked what they heard and pressed an album of some of the songs that at one point outsold all of the official Dylan material. That album, Great White Wonder gave rise to the whole bootlegging industry and fueled Dylan fans’ obsession with unreleased sessions and alternate versions of favorite songs. It took until 1975 for Columbia Records to decide to release an official version of The Basement Tapes, but many fans were disappointed with what was offered to them. Robbie Robertson of The Band was brought in to clean up the music and add overdubs to make the package marketable for a ‘70s audience who expected high production values.

The Basement Tapes Complete doesn’t retain any of Robertson’s additions and has opted for a “warts and all” approach, complete with guitars, voices and instruments falling in and out of tune, and songs beginning and ending without notice. Many of the original source tapes had been sitting in Garth Hudson’s storage in Ontario for decades before he became worried about the extent of the degradation of the reels and took them to Jan Haust, a music producer from Toronto who did his best to restore them to their original condition.

Everyone who listens through this music will have favorites of his or her own. I’ve really enjoyed hearing Dylan singing old Johnny Cash classics like “Big River,” “Belshazzar” and “Folsom Prison Blues.” There are all kinds of oddities like Ian Tyson’s “Song for Canada” (a tip of the hat to his north-of-the-border bandmates) and “See You Later Allen Ginsberg” that are just too weird for words. The ramshackle versions of Dylan’s old material like “Blowing in the Wind,” “One Too Many Mornings” and “It Ain’t Me Babe” are awfully cool and provide a frame of reference for his return to the concert stage at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969. The amount of material in the six-CD set is staggering and should have things that even the most ardent Dylan enthusiasts haven’t heard. If this music is completely new to you, I envy the experience of hearing Bob Dylan as he has never sounded again. Take your time, shift your sonic expectations and enjoy some of the most daring, creative and truly beautiful music ever recorded.

The Basement Tapes Complete is also available in an abridged two-CD format, The Basement Tapes Raw.