Church of Marvels by Leslie Parry

The Circus and the City

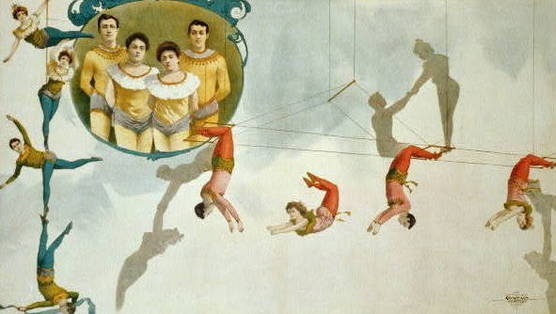

Illustration: The Phenomenal and Fearless Potters, c. 1900 Books Reviews

“When I do a song,” Ray Charles once said, “I like to make it stink in my own way.” When portraying urban life in turn-of-the-century America—particularly the abject squalor of New York tenements as Jacob Riis captured it in How the Other Half Lives—a writer’s first challenge is to make the city feel real. First and foremost, that means saturating the reader’s senses with the same nauseating air the characters are breathing, suffused with the stenches of horse manure, rotting meat, tenement air-shaft trash, bilge water and the amalgamated sweat and grime of thousands of unwashed humans cramped into too-small spaces. The second challenge is not merely to make the city stink, but to do so in the writer’s own way.

Backhanded compliment though it may seem, that’s precisely what Leslie Parry has accomplished in Church of Marvels, a mesmerizing new novel of 1895 New York, situated squarely in the city’s rankest, dankest back alleys, flophouses, brothels, prison cells and opium dens. From the book’s opening pages, which concern a crew of “night-soilers” harvesting the feces from tenement privies for delivery to a riverside fertilizer factory, the novel reeks of authenticity. The only way to come up for air is to close the book, made increasingly difficult by Parry’s eye-popping prose as the story digs in.

Backhanded compliment though it may seem, that’s precisely what Leslie Parry has accomplished in Church of Marvels, a mesmerizing new novel of 1895 New York, situated squarely in the city’s rankest, dankest back alleys, flophouses, brothels, prison cells and opium dens. From the book’s opening pages, which concern a crew of “night-soilers” harvesting the feces from tenement privies for delivery to a riverside fertilizer factory, the novel reeks of authenticity. The only way to come up for air is to close the book, made increasingly difficult by Parry’s eye-popping prose as the story digs in.

One wonders what sort of phantasms haunt the imagination of a writer who can see (and smell) such century-old squalor so vividly, let alone reproduce it so convincingly on the page. Even if Parry didn’t have a fantastic story to tell, she would have achieved something marvelous in Church of Marvels simply by enveloping the reader in such an astoundingly realized bygone world.

Church of Marvels tells the story of Sylvan Threadgill, a dogfaced, twice-orphaned night-soiler and bare-knuckled boxer who discovers a newborn baby abandoned in a lower east side privy; Belle and Odile Church, a disappeared sword-swallower and her knife-throwing sister from a defunct family-run Coney Island circus sideshow called the Church of Marvels; and Alphie, a trick-turning Bowery Rembrandt haunted by a terrible secret. It’s a novel about a city whose bright lights cast the world’s darkest shadows, as Belle describes it, and an invisibly connected collection of born circus freaks who don’t seem to belong anywhere. Discovering what connects them—and how they find one another once their connections become clear—makes for wonderfully gripping reading.

Although few readers would want to trade places with Church of Marvels’ cast of misfits, Parry makes them remarkably sympathetic, not least because everyone else in the book treats them so badly. Belle’s, Odile’s and Alphie’s back stories, in particular, gracefully unravel through half-understood hints and glimpses, with essential clues always left in shadow. Even as a first-novelist, Parry appears to have mastered Hemingway’s technique of storytelling-as-information strategically withheld.

Many of the book’s most harrowing scenes concern Alphie, a mortician’s wife mysteriously imprisoned among criminally insane women on Blackwell’s Island for reasons that slowly become clear to the reader and to Alphie herself. Alphie’s ugly past as a Bowery prostitute and gifted face-painter, and her doomed marriage to an opium-addicted former client, make her desperate hope that her husband will come to save her—and her growing understanding of how unlikely that is—all the more compelling.

Likewise, Odile Church’s efforts to sift through the wreckage of her past and present, the destruction of her family through a fire that killed her mother, demolished their theater and seemingly drove away her sister, provide much of the book’s fascination as its mysteries unravel. Ultimately, it’s her dogged search for her sister, with all its intriguing and unexpected twists, that brings Church of Marvels’ multiple narrative threads together.

Sylvan, meanwhile, every bit as well-intentioned as he is ill-fated, embodies a sort of naked aspiration, not specifically for wealth or comfort, but for any lot less constricted and circumscribed than his own. Sylvan’s musings as he walks along the Bowery’s polluted wharf capture how vividly he and Parry see a world neither of them could have possibly known:

Sometimes he thought that if he’d grown up with another life—in that room with the crying woman in the white kerchief—he might have learned how to swim. He might have been a man who dove beneath the slick, baked water of the river, down to the coldest depths, to the black ragweed bed and nests of hoggleweed. He might have glided through mazes of fallen cargo, prizing open crates, turning out the pockets of drowned men and scavenging shipwrecks for loot. He imagined swimming through the sunken pavilion with turtles and eels, twisting glass baubles from old chandeliers, wresting caviar spoons from the river-shrubs. But instead the sight of the river—sucking at the rust on the hulls, foaming and whipping in the morning wind, tossing flotsam on its way to the sea—only made him sick.

Sylvan’s description of the river—the real river, the one that sickens him—like Church of Marvels itself, is not a sight or a stench for the faint of heart. But it’s utterly arresting and beautiful in its unflinchingly ugly way, a creation of striking visceral impact from a novelist of unmistakable storytelling gifts.