Percy Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias” is often read as a meditation on the absurdity of the ego. In 14 concise lines, Shelley exposes the vast chasm between the ego’s aggrandized self-importance and its actual importance in the grand scheme of things.

This standard reading of “Ozymandias” works, but it can go deeper. More than just mocking it, Shelley reveals the ego’s obsession with its own fragility, its nagging anxiety about its ultimate fate. Death is so terrifying to the ego that it will do anything to be remembered, even build a monument to itself in the desert, an environment where even the ground itself lacks permanence.

Dr. Dre has been worried about his legacy since at least 2000, when his Grammy-winning song “Forgot About Dre” led the promotion of his album, 2001. 2001 was released seven years after Dre’s debut album, The Chronic. Between those releases he had launched multiple careers and a record label, as well as amassed a massive amount of money, but somehow he wasn’t satisfied. Dre wanted the glory. He wanted his life to be a never-ending victory lap, his name to be eternally revered.

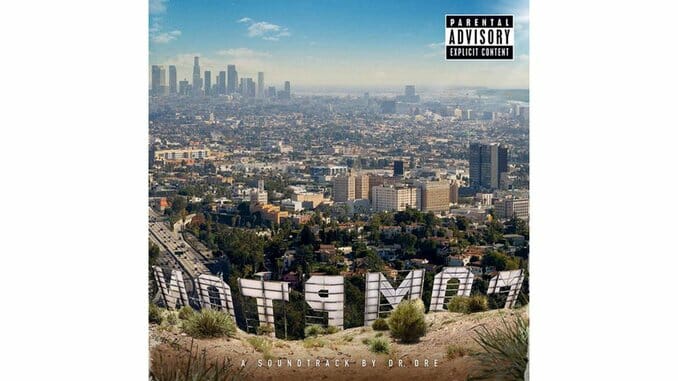

Between the releases of 2001 and Compton, he has mostly repeated the cycle he established between The Chronic and 2001, introducing the world to artists like 50 Cent, Game, Kendrick Lamar, and now King Mez, alongside making large amounts of money from audio technology. These successes are triumphs in their own right, but Dre still wants to trot on that treadmill of glory. Hence, Compton,” Forgot About Dre” the album.

Few people have likely ever listened to Dr. Dre albums to hear Dr. Dre himself, but on Compton it’s hard not to listen for him. He’s been away for 16 years, after all. It just feels appropriate to expect him to answer a few questions. Is he really giving up on Detox? Why? What is Detox at this point? A hard drive full of Game freestyles and Schoolboy Q choruses? How much does he bench? Is he still a Raiders fan? Does he like trap music?

All of these questions are game for someone returning from a self-imposed exile, but throughout Compton, Dre focuses on his mythical origin story rather than how it all unfolded. For instance, “It’s All On Me” begins as a reflection on his myriad pressures, but then it quickly becomes a strange Cliff Notes version of his history in the music business. Elsewhere, on “Issues” he alludes to being a member of N.W.A and on “Satisfiction” he alludes to “Gin and Juice” as if these are the highlights of his life. There’s nothing wrong with self-reference, but what’s striking is that the past Dr. Dre seems to be the only self he has access to.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Dr. Dre has always been a pharmacist rather than a general practitioner, a gateway rather than a destination. And the gateway on Compton leads to interesting places, lush compositions and adept performances. Newcomer Anderson .Paak’s appearances are particularly memorable. On “Animals,” his raspy voice perfectly hits that delicate note between suffering and indignation, protracted pain and the thirst for vengeance. Similarly, on “All in a Day’s Work,” he stretches his voice to the limit, using his own strain to give lines like “I’m on my grind, fuck the part time” some additional strength.

Other feature artists also make hefty contributions, especially the guest producers. It’s hard to parse their individual contributions from the lengthy liner notes, but on songs like “For the Love of Money” and “Genocide,” some of the few songs with a single credited producer, there’s some striking production. On the former, producer Cardiak samples Bone-Thugs’ “Foe the Love of $” and injects it with a sedative, bringing out the song’s tragic undertones. When Jill Scott murmurs “looks like it’s raining money, man,” the rain feels like a curse rather than a blessing, a destructive flood rather than a restorative storm. On “Genocide,” producer Dem Jointz collates airy synths and hollow scales that fade in and out between robotic grunts and spacey chimes. The beat feels simple until Kendrick Lamar emerges and spits an obstacle course run of a verse, nimbly navigating his words through the instrumental’s many moving, flaming hoops.

This kind of impressive production is found throughout the album and virtually all of the vocalists rise to the occasion, even Dre himself. Still, even with its many merits, it’s hard to take this album at face value. Not only has the album allowed Dre to quietly wash his hands of a mythos of perfectionism and secrecy that he cultivated for over a decade at the expense of fans’ and other artists’ time and energy, but it’s being released as a soundtrack to a movie about his life that he executive produced. Plus, the majority of the featured artists are signed to his label, Aftermath, or have some historical connection to Dre’s previous work. This isn’t so much an album as it is a living monument, a ribbon-cutting ceremony for a museum that Dre funded, built, owns and operates. “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair” is no longer a phrase: it’s a business plan.

The listenability and creativity of Dre’s grand scheme almost save Compton from itself, but it’s the final song of the album that brings down the house. “Talking to My Diary” is framed as a confessional, an intimate look into Dre’s mind, his anxieties, his secrets. And Dre himself even seems to think of the song that way, declaring, “a nigga having flashbacks!” in the middle of a verse as if he’s recalling pivotal moments in his life. But the chorus says it all. Dre doesn’t describe his diary as having “no ink in the pen and no lines on the paper” because he’s just that committed to the spoken word. His diary is empty because he hasn’t written anything in it. His recollections are so impersonal, so devoid of any human experience, that they don’t even seem ghostwritten. When Dre shouts out the members of N.W.A it feels less like a vivid recollection of moments lost in the mist of time and more like a tiny acknowledgment section bookending the second edition of a best-selling, self-published biography. Dr. Dre’s diary is probably his checkbook.