The Future of Craft Whiskey according to the Innovative Tuthilltown Spirits

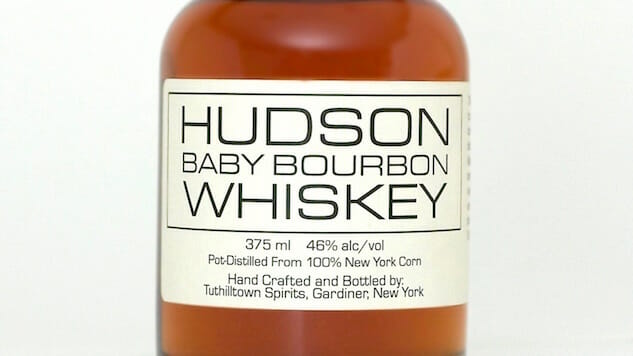

Photos via Tuthilltown Spirits Drink Features Tuthilltown Spirits

The American craft distilling movement is as strong as it’s ever been, and continuing to grow as small producers pop up across the country. It’s easy to overlook that much of this progress happened over the past decade, as aspiring distillers dusted off old recipes and started to reenergize a market that in many ways was still struggling with post-prohibition stagnation.

One of the early entrants to modern craft distilling was New York’s Tuthilltown Spirits, producers of the acclaimed Hudson Whiskey line, as well as vodka and gin brands. Hudson Whiskey (the brand since 2010 has been owned by William Grant & Sons) has seen some impressive growth over the past 10 years. It was also a big player in paving the way for the larger distilling boom in New York state, lobbying for the passage of the state’s farm distillery law in 2007 (itself coming up on its 10-year anniversary). It’s safe to say the folks at Tuthilltown know a thing or two about producing and selling whiskey in the U.S.

Paste recently got a chance to catch up with founder Ralph Erenzo to get his perspective on how craft distilling in the U.S. has changed over the past decade and what he sees for its future.

Tuthilltown founder Ralph Erenzo

Paste: Hudson has been in the game a while now. What was the U.S. craft distilling environment like when you started in 2003?

Ralph Erenzo: When we started, there were probably – I’m guessing — about nine small craft distilleries in the U.S., and none in New York. There were no distilleries at all in New York. And so, when we started, the industry was very primitive. It was just starting to get up on its feet. Actually, it was just starting to crawl.

There was none of these long shelves of books in bookstores about how to build your own distillery, how to make whiskey, how to make moonshine. Now those books are everywhere.

My partner and I came from non-alcohol industries, so we really were starting from scratch. And now I think there are 1,500 small distilleries around the country, and dozens of books on “how to,” and articles on it. In New York, there are 135 distilleries. We were in operation for four years before anybody else opened another distillery in New York.

Paste: You clearly had a head start on the competition. What helped spur the growth in distilleries in New York?

RE: In 2007, the Farm Distillery Act was signed into law in New York. Since 2007, those 130-or so other distilleries opened up. That law came with an obligation [for distillers] to use at least 75% New York-grown agricultural raw materials. It also came with the ability to have a tasting room and sell directly to consumers and offer samples. That opened up the whole tourism aspect that wineries and breweries, and that’s what kicked off the industry.

Paste: You advocated strongly for that law. Did you regret the increased competition that developed after the law was passed?

RE: When we started, I didn’t really have to sell my goods. I could walk in and all I had to do was say that this was the first whiskey made in New York since prohibition and it was a pretty fast sale. And there were no other craft whiskies on the shelves in the retail stores or on the bars. But now, there’s a whole wall of New York goods and artisan beverages. The competition is lot stiffer now.

[Being first] is a double-edged sword. Being the only one operating in a state, when I went to Albany to try to change laws, and they would ask me “who’s this going to benefit?” the only answer I could give was, “It’s going to benefit me.” Now, it’s a whole industry in New York.

Paste: Aside from more competition, what were some other ways the law affected how you did business?

RE: It was a huge step forward. It also was a great way for us to actually build a relationship with the state liquor authority. Up until then, nobody in the alcohol business ever called them with a question. Because their mandate was only to regulate, not to support.

Since [2007], it’s completely changed. The state liquor authority is working with the industry. In fact, now, when they go to suggest a change in law, they’ll call the guild in New York. Or they’ll send it to me first and say, “what do you think about this?” And that’s a complete 180-degree change from when we started.

Paste: And there was recently another change to the law?

RE: Now you can sell for consumption on-premises. That opens the door to a whole new range of business that the producers can do.

Paste: How do you think that competition will shake out in the coming years? Is the pace of growth in the distilling industry sustainable?

RE: It’s surprising how successful the industry is across the country. There’s now a New York State Distillers Guild, there’s the American Craft Spirits Association. All of these have come to be in the last five years or so.

In the next year or two, I think what we’ll see is a lot of the start-up distillers who are not as committed to it will fall by the wayside. Either because they’re making bad product, or because they don’t have enough capital, or they’re bad businesspeople. It’s a difficult enough business that if you don’t have those things going for you, you’re likely to fail.

Paste: So you’re saying making craft whiskey is not a slam-dunk way to make a ton of money?

RE: There are a lot of people who have gotten into the industry in New York and nationally who were investment bankers or lawyers or something and they got into it because it was cool and they thought they’d make a lot of money. And then they found out that if you want to make a lot of money at distilling you’ve got to start with a lot of money, because you have to build a big facility. You have to have people that know what they’re doing and you have to have the money to put it on the marketplace.

People get into the industry thinking they’re going to make a big killing — that they’re going to be the next Grey Goose. And they don’t realize how long it takes to do all of this and how much money is involved. They either start out too big or their expectations are too big.

Paste: In your opinion, what needs to happen to keep the industry growing?

RE: The first thing I always say is infrastructure. People are building distilleries like crazy, but nobody is building malt houses or cooperages or other things that support the industry and make it successful. Distilleries and breweries are all buying their barley from Canada or Washington state or Germany. New York growers, when the industry died after prohibition, got out of the habit of growing barley and malting barley. So those things all closed down and they don’t exist anymore.

Paste: It seems like cost of selling whiskey, especially for small producers, will be prohibitive going forward?

RE: Part of the problem is the high cost of making small whiskey. Some of the producers down in Kentucky, for instance, make batches of 5,000 gallons or 10,000 gallons a pop. And the small distillers are talking about 100 to 500 gallons a pop. The economies of scale for big producers keep costs much lower.

Also, breweries and wineries in the U.S. pay excise tax. If you make less than a certain number of barrels or gallons of wine, then your excise tax rate drops. It’s not the same for small distilleries. We pay the same excise tax rate as the folks at Jack Daniels. That rate is $13.50 per proof gallon. A proof gallon is a gallon at 50% alcohol.

[Craft distillers] have a bill that we’ve been lobbying for in Washington, D.C. for the past eight years to try and get parity with the wineries and breweries. That parity will drop the price of craft goods significantly. It’s the difference between paying $13.50 per proof gallon and paying $2.40 per proof gallon. We would save enough in a year to buy two stills and hire two people when that bill passes. It would help the small distillers to be competitive in pricing.