Gabriel Tallent Talks Abuse and Identity In His Haunting Debut, My Absolute Darling

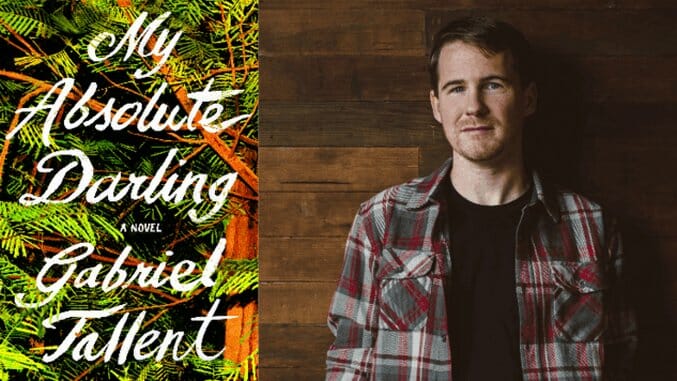

Author photo by Alex Adams Photography Books Features Gabriel Tallent

My Absolute Darling is a near impossible book to categorize. While it centers on a young girl’s isolation as she struggles against an abusive father, it’s also a deep meditation on language, nature and the way we perceive our world. Debut author Gabriel Tallent eschews feel-good plot turns, instead offering an emotionally closed-off heroine who is determined to save herself. Philosophical but without pretense, the novel proves a fascinating examination of personal strength.

Fourteen-year-old Turtle Alveston and her father, Martin, live on a large plot of land on California’s Mendocino Coast. Martin believes the fall of civilization is fast approaching, and he forces Turtle through harsh training in order to prepare for the future. He also abuses her sexually, verbally and physically, with his moods erring towards a desire to punish her. As a result of her mistreatment, Turtle has internalized Martin’s misogyny and vulgar cruelty, which manifests as a warped vision of her identity.

“I was always deeply engaged in stories, novels, philosophy that talked about how to be a good person and how to live a just life in the face of injustice and tragedy,” Tallent says in a phone interview with Paste.

With My Absolute Darling, Tallent amplifies the injustice surrounding Turtle. Although Martin’s behavior is abhorrent, his community is complacent in a way that allows him to continue abusing Turtle with little fear of repercussions. After an accident, for example, a friend named Jacob encourages Turtle to go to a doctor by assuring her that no one would report her to Child Protective Services. This sense of not getting too involved in people’s private lives leaves Turtle to rely on her own skills and moral compass, a challenge given her upbringing. But Tallent writes her with a fundamental sense of care and goodness, which enables her to fight back against Martin’s influence.

Martin looms large in the story, but it’s Turtle’s narrative. We see the world through her eyes, which creates a warped, fish-eye effect. Turtle’s own motivations are striking, but she doesn’t know everything about her father or the world around her. We’re limited in the same ways as Turtle, a conscious choice Tallent made while writing.

“I grappled with having written a great deal about Martin, but ultimately decided this wasn’t his story,” he says. “I decided he wouldn’t tell her [about his past]. We don’t always know what shapes the most important people in our lives, but I also don’t think it really matters. What matters is what they show up as.”

This limited access to information cuts both ways; reading the book, it’s important to remember that others don’t have the same full picture of how Turtle’s mind words. “You have access to Turtle’s mind that in a way that makes her more lucid. If she was in your life and you weren’t Jacob, she would be a difficult person. It’s our particular vantage point that makes sense of her.”

Martin’s influence is most clearly seen in Turtle’s language, which is littered with insults Martin has directed at her. She sees herself as stupid, ugly and her own worst enemy, but she’s aware that Martin’s perception of the world is flawed. “Turtle’s world view is molded by this very charismatic, very domineering personality, and she has trouble seeing the world in a different way,” Tallent says. “You see her parroting him, but at the same time you can see her coaching herself through seeing things he has described through a new light.”

Turtle sees what Tallent describes as a “sickness” in Martin’s approach to the world, and “when she observes this, she returns to her own world view and assesses herself for the same sickness.” When she first meets Jacob and another boy named Brett, she has already begun to see this. But the boys’ own use of language reveals a new world to Turtle.

“Turtle has a very literal grasp on language, but Brett and Jacob have a literally fantastical, playful grasp on language and use it in a non-literal means of self-identification,” Tallent says. “It opens up her sense of what’s possible and you can see her engaging with and trying to make sense of the boy’s strategies.”

While Jacob and Brett are key to helping Turtle reimagine her world, only Turtle can save herself. Tallent points out that it isn’t realistic to expect teenage boys to swoop in and save an abused girl, but this doesn’t mean their influence is insignificant. Rather, it’s a representation of the way people shape others’ lives.

“We sometimes meet people who…move us so deeply, but who aren’t able to be our rescuers or change our life circumstances,” Tallent says. “Sometimes they provide a little bit of a galvanizing force when we’re working on ourselves. [Jacob] plays the role of a friend and a love interest, but he can’t save her.”

The novel’s premise makes it easy to assign cliché lessons to it about survival, community or good versus evil. But My Absolute Darling challenges that simplicity by allowing Turtle to define her own reality.

“What saves Turtle is trying to see the world clearly and, particularly, to see the other people in her life clearly,” Tallent says. “One of the most important lessons…[is] to take other people seriously on their own terms, as people as important as you whose experience may or may not be accessible but are so much more than set pieces in your own life.”

Bridey Heing is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC. More of her work can be found here.