Disney Nonplussed: The Global Politics That Made The Three Caballeros

75 years ago, U.S. colonialism and world war fears gave Donald Duck his entourage.

Movies Features Three Caballeros

With Disney Plus opening up the floodgates to the Mouse House’s oldest and most obscure movies and television, many subscribers are catching up on half-remembered childhood entertainments that have long languished in the “vault.” The Three Caballeros, now 76 years old, might not be the weirdest one in the whole catalog, but it has one of the strangest pedigrees of any movie whose characters are still bopping around in Disney properties and at the theme park as recently as 2018 at least.

Donald Duck made his animated debut in 1934. His pan-American friends—Brazilian parrot José Carioca and Mexican rooster Panchito Pistoles—have been hanging around with him on and off almost as long as his nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie (introduced in a comic in 1937). The story behind Donald’s Central and South American buddies is almost as peculiar as the trippy animated feature where they first appeared together in the waning days of World War II.

It’s Donald Duck’s birthday, and he receives a care package from his friends in Central and South America. Opening the gifts, cartoon logic quickly takes over, reuniting Donald with his two friends for musical numbers and magical trips to far-flung parts of the Americas.

Donald serves as the loose connective tissue between a grab bag of animated shorts and musical numbers that feature a blending of live-action Latin American stars with animated environments and characters. After an opening cartoon about a penguin fed up with Antarctica who relocates to the tropics (narrated by Sterling Holloway, the original Winnie the Pooh), and a story about a young boy who discovers and tames a winged burro, the movie introduces José, Donald’s friend from Brazil. It’s at this point the movie proceeds to zag into weird impressionism as Donald is transported to Brazil (specifically to Salvador in the state of Bahía, based on the skyline, though the movie never names the city).

It’s at this point, shortly after José and Donald join up with Panchito that we’re treated to the title musical number and the movie shifts from cute cartoons to a full-on musical, with each number providing the backing to abstract animation or the characters dancing alongside (and really shamelessly salivating over) real-life Latin American dancers. The Three Caballeros was actually the first attempt by Disney to ever combine live action with animation, more than 40 years before Who Framed Roger Rabbit? would kick off the beginning of the company’s “renaissance” with its mastery of that particular technique.

If the movie has any clear through-line at all, it’s that Latin America is a spicy and happening place with a lot of cute girls who don’t mind if you ogle them. There are a few moments that skirt the bounds of respectful portrayal of minorities by today’s standards, but it’s clear Disney’s animators and directors are trying their darnedest to make you think South and Central America are awesome (partly by leaning heavily into exoticizing them).

To understand why Disney would embark on a good will tour of the United States’ neighbors, you have to go back to America’s second-favorite president named Roosevelt and the geopolitics of 120 years ago. In 1905, on the heels of incidents that had seen European powers send military forces to the Western Hemisphere to collect debts in South America, Theodore Roosevelt made what has been dubbed the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It in essence made it American foreign policy to intervene militarily in cases where instability in the Americas made it seem like other countries would invade. Roosevelt (and moneyed North American interests) didn’t want to contend with Europe for dominance of Central and South America.

It ended up being the catalyst for a lot of horrendous U.S. adventurism south of the border, with bloody interventions in Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti and the Dominican Republic to show for it—all of which, a scholar of history might note, ended up under ghoulish dictators in the wake of U.S. involvement. By 1934 (the nation having elected a different Roosevelt), the United States reversed course somewhat, and adopted the “Good Neighbor Policy,” a foreign policy that took the emphasis off military invention and stressed cultural and diplomatic exchange instead.

Guilt may have had something to do with it, but there was another motivation: with Europe consumed by Nazi conquest and the prospect of war looming on the horizon, the United States feared that some people in Latin America might be mobilized against the Americas.

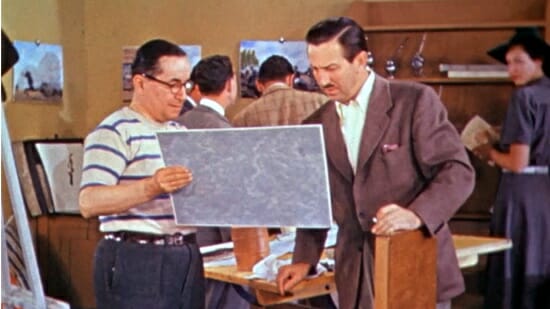

It was against that backdrop that Disney sent animators down to Central and South America to gather material for a slate of cartoons aimed at extending a friendly hand to the United States’ neighbors. The José Carioca character actually first appeared in 1942 in the short film Saludos Amigos, which consists of a few cartoons set south of the border with other scenes of narrated travelogues of the studio’s animators. The studio used what it learned to produce the more ambitious Three Caballeros a couple of years later.

The movie sort of meanders through musical numbers until it ends, and remains memorable mostly due to how weird it is and how unforgettable the individual songs are. What’s noteworthy is that Donald’s friends have continually popped up over the years to inject some Latin flavor into his life—the sharp-eyed will even note that José is lingering in the background of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. From the occasional cameo to recurring parts in TV shows and even a full season of The Legend of the Three Caballeros in which the trio fight mythical monsters, Disney’s animators have remained determined to revive the pan-American trio and occasionally bust out their eponymous musical number. (They have quietly reworded the lyrics “We’re three caballeros/three gay caballeros,” sadly.)

Three quarters of a century later, Donald Duck’s best buds—the ones Disney made because the United States was trying to atone for colonialism and terrified of Nazi Germany and trying to court Latino viewers when courting Latino viewers was barely even a thing—are still regular cameos and reliable fan favorites. They predate Castro’s revolution and stem from the same geopolitical preamble to it and you can stream them to your living room, if you want.

Kenneth Lowe wants to know, as you Americans say, what’s cooking. You can follow him on Twitter and read more at his blog.