When Bob Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles, Vol. One, appeared in 2004, I approached the book with a mix of anticipation and trepidation—tantalized by the possibilities of Bob Dylan telling his own story, but resigned to the likelihood of suffering through 256 pages of Tarantula/“Outlined Epitaphs”-style inscrutable verbal noodling.

Chronicles turned out to be a bit too episodic to constitute anything like the whole story of Bob Dylan, but each episode proved fascinating, evoking times and places and characters in Dylan’s orbit as only Dylan himself could, in prose more coherent and lucid than most expected Dylan to write. If it left readers with the suspicion that this charming, unassuming storyteller was simply wearing his “candor” mask—the same mask Dylan would don in the interview segments of Martin Scorcese’s No Direction Home two years later—Chronicles nonetheless proved an immensely satisfying and rewarding read.

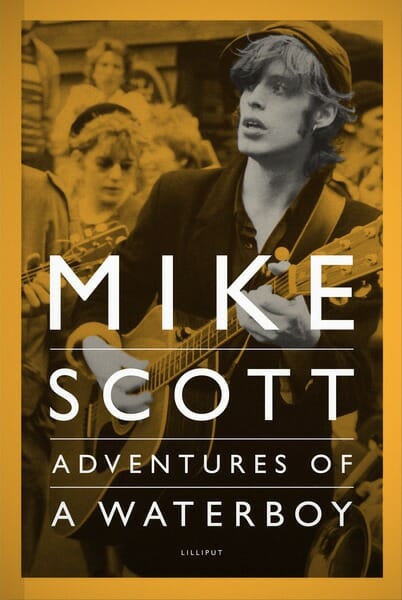

Adventures of a Waterboy, the new memoir by Waterboys founder and longtime bandleader Mike Scott, similarly defies expectations. Penned by a Scottish roots-rock icon who reputedly spent much of the defining decade of his 30-year music career refusing interviews, squashing fanzines, disappearing for years at a time in the Celtic mists and generally refusing to let the story of his life, loves and music be told by anything but the music itself, Adventures of a Waterboy turns out to be surprisingly revealing and direct.

Scott recounts his adventures among friends and lovers, music and the music business with all the verbal dexterity, insight, wit, intensity, clarity of purpose, and soul-baring, ecstatic awe that made Waterboys songs like “The Whole of the Moon,” “A Church Not Made With Hands,” “Fisherman’s Blues,” “The Pan Within,” and “You in the Sky” resonate so powerfully with the band’s fans through the years. The book takes readers on a rollicking journey through the ’80s UK pop-rockscape. It presents roots-rock excavations of formerly rootless third-generation rockers … and the adventures of a man and a band that never came close to making the same record twice.

Like Dylan himself, Mike Scott has spent much of his career bidding restless farewells to music styles and scenes, ever in search of a new sound and new sources of inspiration. If you’re a Waterboys fan, or ever were, your impression of the band and the kind of music it makes (or made) likely depends on where and when you climbed aboard. Some tuned in to the sax-driven, bombastic “Big Music” of A Pagan Place and This is the Sea, and were caught off guard by the rootsier and folkier sounds of Fisherman’s Blues and Room to Roam. Others heard Fisherman’s Blues first and worked backward. Wherever you came in, you probably had that “I couldn’t believe it was the same band” moment Waterboys fans so often seem to recall.

In truth, what you heard really wasn’t the same band.

It’s hard to think of anyone in rock who has gone through more drummers than Mike Scott and the Waterboys. (Scott says the Fisherman’s Blues sessions alone featured 15 different drummers.) While, Scott seems to have loved and admired all the drummers he worked with, none seemed for more than a year or two (or sometimes a session or two) to help him create the sounds he heard in his head. Adventures of a Waterboy doesn’t always make complete sense of Scott’s personnel decisions (particularly when it comes to his endless stream of drummers and managers), but it comes close. If Scott’s choices seem inexplicable to the reader, the writer himself also seems to be scratching his head at his younger self.

Adventures of a Waterboy honestly chronicles how many wrong turns a popular artist can make for the right reasons. The ’80s incarnations of the Waterboys fascinate us not just because of the music the band members made and the adventures they had making it, but because they looked like rock’s Next Big Thing for so long. (As a result, they enjoyed the freedom of taking their time making records.) The Waterboys logged some of the legendary shows of the decade, and recorded two of its indelible albums (This is the Sea and Fisherman’s Blues), yet Scott’s resistance to stardom grew almost as famous as the band itself. He refused to make videos, and he allegedly blew off a chance to lip-sync “The Whole of the Moon” on Top of the Pops, the UK equivalent to American Bandstand, to go jam in a London studio with Dylan instead. (In his book, Scott insists that the Top of the Pops story is myth … even though he describes the Dylan session in much comedic detail.)

Scott once wrote a song called “Lucky Day, Bad Advice” that laid out all the bad career counseling he received in the ’80s about how he could take the Britpop world by storm. It’s hard not to applaud Scott’s determination to prevent the Waterboys from becoming a U2 clone, or (worse) another New Romantic synth pop/wedge haircut band—and to distance himself from anyone who’d try to shoehorn him into one music industry convention or another. But he seems to have received very little in the way of good advice at the Waterboys’ tempestuous commercial peak, with one notable exception: a friend famously told him to “get on the bus” and get out of the London rock scene closing in on him in late 1985. This advice precipitated Scott’s decision to move to Ireland, where his own (and his book’s) most exciting adventures take place.

With the move to Ireland on New Year’s 1986, Scott joined forces with Irish rock fiddler Steve Wickham (then best-known for the ringing, martial electric fiddle on U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday”) and began the Waterboys’ deep dive into roots music. It started in Dublin with old country and gospel and blues records that Scott, Wickham and sax/mandolin-playing bandmate Anto Thistlethwaite absorbed and transmuted into wild and spontaneous sounds captured at the band’s landmark Glastonbury ’86 show, and on hundreds of hours of tape at Dublin’s Windmill Lane studios that year. Nearly three years would pass before Scott figured out how to distill those sessions into side one of Fisherman’s Blues.

A year or so into the Irish adventure, the sounds Scott heard in Dublin’s traditional music session pubs, as well as the pressures of trying to fashion an album from the overwhelming surplus of recorded material, pulled the band in a different direction. Here Scott’s musical adventures and writing take flight:

To enter a Dublin bar and find a gaggle of musicians firing off joyful, celebratory music is a delightful experience … Here was a wild, articulate music that expressed the soul of Ireland and evoked its landscape, played with power but without machismo, with mastery but without ego … The charms of traditional music emerged from the mist as eternal verities to be envied and achieved, emanations from a world far removed from the manipulative, distorted ghetto of the rock business.

As ever, Scott decided to let the music, rather than the music industry, dictate his next move. He rented a cottage in Spiddal, a remote fishing village in County Galway in the famously musical west of Ireland, and fully immersed himself there in traditional song, through sessions and records. Scott’s book offers a rapturous recollection of a pre-Celtic Tiger Galway where much of the country’s ancient past seemed ever-present and much alive. For Scott, that sense of Celtic continuity stretched beyond Ireland itself. One thing he learned from records—the Celtic music he heard was as much Scottish as Irish. “As a teenager” in Edinburgh, he writes, “I’d considered Scottish folk music a hinterland of kilted buffoonery. Now I heard it anew, and the music I was in love with was the music of my own ancestors.”

When the band relocated to Spiddal (adding some traditional musicians along the way, including international-star-in-waiting Sharon Shannon), it took on a new character. No longer simply a performing and recording act assembled as an extension of Scott’s songwriting, it transformed into a true traveling ensemble. Concerts became simply temporary interruptions of the band’s never-ending traditional music sessions in pubs and around kitchen tables.

Scott recalls this period as a sort of pinnacle of his music career. He found personal rewards in playing music rooted in an age-old tradition and in no way yoked to the contemporary pressures and demands of the rock music industry. Best of all, in the “raggle-taggle orchestra” the Waterboys had become, Scott found himself “abdicating from the roles that had been mapped out for me, both by others and by my younger self. I was a singer and musician, not a rock star.”

Scott’s adventures as a Waterboy didn’t begin or end in the ’80s, though that proved the commercial heyday of the band, and even though the Waterboys-as-we-knew-them imploded spectacularly in 1990. Scott sets up the book with a wonderful anecdote about meeting Patti Smith (who inspired the Waterboys’ first single, “A Girl Called Johnny”) when he worked as an 18-year-old fanzine editor in 1978. From this encounter, Scott learned how hard it was, even for rock’s archetypal anti-star, not to act like a rock star and a dictator when feeling her oats.

Scott continues deep into the ’90s, discovering meditation and a new, more enriching life (along with a wife) as part of a spiritual commune in Scotland. He also writes about more solo and Waterboys records, more prickly encounters with the record industry and cathartic reunions with his long-lost father and estranged fiddler Steve Wickham. Oddly, the book ends in London in 2000, on the verge of Scott’s return to the contemporary British rock scene with A Rock in the Weary Land.

This last choice strikes me as the one really odd one Scott makes as a writer of this book (as described earlier, he made plenty of odd choices as a bandleader and recording artist). In the last 12 years, Waterboys made some terrific records that have gone unnoticed even by many former fans, especially in North America. If Scott plans a sequel (as the foreshadowing of life events still to come in the book’s last pages suggest), it might prove a hard sell if focused exclusively on 21st-century adventures.

It ends too early. Adventures of a Waterboy is a wonderful, eloquent memoir, a captivating, often transcendently evocative read for anyone interested in the “roots music” impulse of rock stars and where it can take them. Waterboys fans learn how the band got from Point A to Point B (and then some) with each unexpected musical turn. The band’s faithful (and even the formerly faithful) will find a long and revealing letter from an old friend—or as Scott once famously termed it, “a bang on the ear,” with all the warmth, wit, cheek, and offhand, unvarnished candor the phrase implies.

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York, and a one-time busker of Waterboys songs in Galway, Ireland. Read more of his book reviews at FirstLookBooksBlog.com.