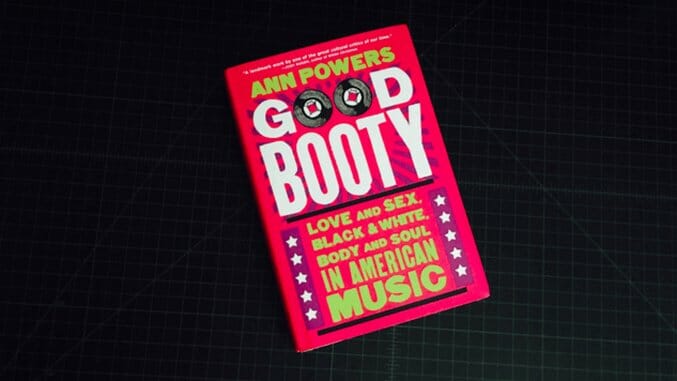

Ann Powers’ Good Booty Shines a Light on Race and Sex in American Music

Photo by Frannie Jackson Books Reviews Ann Powers

In her new book, Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music, Ann Powers makes the compelling argument that American music is best illuminated by studying the erotic symbolism and power of each generation’s musicians. By examining the history of American music through this lens, Powers identifies the precise limits of what Americans are willing to tolerate—and just how much further we still have left to go.

“In every era,” she writes, “expressing the erotic through music has required Americans to confront the ways in which this culture is grounded in exploitation and violence as well as democratic openness and liberty.” We may be a democracy, but we’re also a settler-colonial society founded by theocratic Puritans; we’re a nation of immigrants whose lasting economic weight owes a great deal to a once-booming slave trade. For all of our advances, we still are, as Gore Vidal dubbed us, the United States of Amnesia. Music, Powers’ suggests, is as close as we can get to self-honesty on a massive scale.

Good Booty opens with a portrait of 19th-century New Orleans, a slave port riven with conflict around race, status and sexuality. In New Orleans, Powers contextualizes the rest of American musical history—wherever music is found, a longing for freedom meets the hard reality of its impossibility. For the era’s black musicians, “music was both a tool of oppression and the weapon that could momentarily defeat it.” Her example here is drawn from Solomon Northrup’s well-known tale of being kidnapped and enslaved despite his legal status as a free man. Northrup’s fiddling allowed him to leave the plantation where he was enslaved and play in different locales. But it “also caused him agony when his keeper forced him to use [his fiddling] as others were whipped until they danced.”

Powers’ strengths are best on display when she writes on individual lives—especially forgotten ones. Take Florence Mills, an androgynous black woman born in 1896 in Washington, D.C., whose sensuous voice gave rise to a complicated national discussion on authenticity and eroticism that is now the norm. Mills rose to fame in vaudeville, specifically in a production called Shuffle Along in which Mills outdid her buxom counterparts by singing a song of longing so real, so stripped of artifice that audiences were overcome with a new intimacy. Powers writes that Mills did a great deal to introduce modernity into music, for “What could be more modern than a woman who could enrapture crowds just by being herself?”

Beyond biography, Powers’ critical insight—in particular her ability to synthesize heaps of scholarly work—is notable. One example is her provocative description of doo-wop as a kind of teenage babble that created an open field for playful discussions about nascent sexuality at a time when society was terrified of this rambunctious new teen identity. But her analysis thins out and the prose dries up at times, particularly in the book’s overlong first chapter. (It’s hard to blame her—the chapter spans a hundred years.) Summary is the sad partner of necessity.

What’s most impressive about Powers’ book is that she never loses sight of her project: to demonstrate eroticism’s explanatory power in American music and to show that for every moment of freedom given, there’s a boundedness that comes with it. In the sexual revolution, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin represented its liberatory power and its self-destructive drive. Around the time of the AIDS epidemic, punk arrived in its de-sensualized and sex-obsessed juvenility. Bands like Fear rose to prominence, dragging their overt misogyny and homophobia in tow, even though Third Wave riot grrrl-style feminism and queercore arrived to combat it later. Turning to more recent events, Powers examines the reification of Beyoncé in the era of #BlackLivesMatter. After reading the book, it is impossible to rewatch Queen Bey’s “Formation” video without thinking back to 19th-century New Orleans.

In short, Powers asks the important questions: Who gets to survive in America? Who gets to speak? Who gets to sing? And who gets to be heard?