The Only Certainty Is Uncertainty: David Burr Gerrard Talks The Epiphany Machine

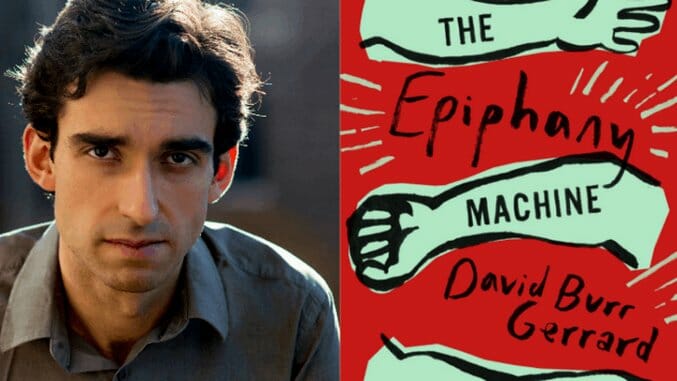

Author photo by Albert Cheung Books Features David Burr Gerrard

“I finished the final copy edit of this book on the morning of November 8th,” David Burr Gerrard tells Paste about The Epiphany Machine over the phone from his home in Queens.

He had just finished voting for Hillary Clinton, as many had in his neighborhood, and the jubilant atmosphere had him concerned that the ending of his sophomore novel was a bit too bleak.

The Epiphany Machine details the personal and social fallouts of those who come into contact with the titular device, which is a kind of sewing machine that tattoos a truth about the user on her forearm. (E.g. DEPENDENT ON THE OPINION OF OTHERS or DOES NOT UNDERSTAND BOUNDARIES or ABANDONS WHAT MATTERS MOST.)

The novel is predominantly told from the perspective of Venter Lowood, whose parents used the machine in the ‘70s and who serves as testimonial collector for the machine’s keeper, Adam Lyons. The machine and its adherents polarizes the populace: Is it a cult run by Lyons and the tattoos it generates just generic bromides? Or does the machine truly reveal deep truths about its canvases? Few things beyond uncertainty can be counted on in life, and that is something in which The Epiphany Machine revels.

As soon as the inevitability of Hillary’s victory reversed itself, and the future Gerrard and his neighbors had envisioned became uncertain, a new inevitability arose: Donald Trump was always going to win. There had been so many signs, we all missed it.

“By the end of the night,” Gerrard says, “I felt much more confident in my book, and much less confident in the country.”

The whirlwind surrounding the election serves as a microcosm for the power that uncertainty can have on a life. Gerrard first conceptualized The Epiphany Machine as a graduate school student; absorbing from his reading that his short stories were meant to end with an epiphany earned. The idea engendered uncertainty in himself and his work.

“Maybe I don’t have any kind of summarizable wisdom to impart,” Gerrard says. “And if I don’t, then what am I doing writing? What am I doing asking people to take time out of their day to read my thoughts if I don’t have any kind of conclusion to come to whatsoever?” Afflicted with a “profound ambivalence” toward epiphanies in fiction, he desired a machine that could crank out a little koan for him, from which he would work backwards and create the story.

In the decade that followed, he worked simultaneously on both his debut novel, Short Century, and on The Epiphany Machine, writing the former while trying to find a way to frame the latter. At one point, the book consisted of testimonials from the machine’s recipients; the breakthrough came when Gerrard realized he was more interested in the person taking those testimonials. Fragments of his other ideas and false starts still remain in the manuscript—to the book’s strength. They imbue it with an organic sense of uncertainty that heightens the reader’s feeling of being unmoored.

So important is uncertainty to the book that the very question at the heart of the story—“Is The Epiphany Machine magic or a con?”—is not known even by the author himself.

“There were times when I had one position or another,” Gerrard says. “But I wanted it to be an open question, both for the reader and for myself. Because for me, all questions are open.”

To Gerrard, the notion is at once frightening and hopeful.

“We really don’t know the answers to the most basic questions of why we’re here, or what we’re supposed to be doing,” Gerrard says. “That makes us look for answers, sometimes makes us look for easy answers. But also offers whatever hope there might be, whether or not we have access to that hope.”

For The Epiphany Machine’s detractors, the device offers not only easy answers but generalities so universally true that they should hardly constitute being called “answers” at all. For those for whom an epiphany leads to life-altering change, the fact that their epiphany happens to be true for many others is hardly an indictment of the its ability to improve their own lives.

“If you’re looking for answers, there are slogans,” Gerrard says. “Literature is about trying on an answer, then trying on a different answer.”

B. David Zarley is a freelance journalist, essayis, and book/art critic based in Chicago. A former book critic for The Myrtle Beach Sun News, his work can be seen in Hazlitt, Sports Illustrated, The Chicago Reader, VICE Sports, The Creators Project, Sports on Earth and New American Paintings, among numerous other publications. You can find him on Twitter or at his website.