A quiet human quest. No rings, no dragons.

You know how it is when you go back to a book or a movie you once loved and discover that either you or it has changed. Either way it’s disappointing.

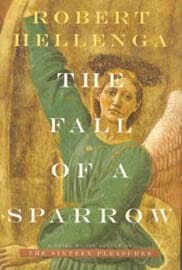

More often than not, I’m disinclined to revisit a fondly recollected favorite for that very reason, but I was lured back to Robert Hellenga’s The Fall of a Sparrow by his latest novel, Philosophy Made Simple, which is, simply, irresistible.

I can now report that Hellenga holds up at least equally well to rereading. His gracefully allusive, comically direct and colloquially complex style delights in much the same way as the blues lyrics that run through his work. Just as with the blues, there is that simultaneous sense of strangeness and familiarity, the feeling that every time you regard the subject, it will refract the light in a new way.

The Fall of a Sparrow is, like Philosophy Made Simple, the story of a man and his three daughters, the stuff of fairy tales, as Hellenga remarks, and like a true fairy tale it’s full of light and dark, promise and menace, comedy and tragedy. In this case the story focuses on a philosophical quest. Well, if that makes it sound too academic, why not just call it a humanistic quest for—meaning? Closure? How to narrow the gap between the inner and outer man?

It is in any case a journey undertaken by Alan “Woody” Woodhull, a professor of Classics, whose oldest daughter, Cookie, was killed in a terrorist bombing of the Bologna train station in 1980. The book ends with a memorial service nine years later and the much-debated choice (it causes the break-up of his marriage) of a gravestone inscription that for Woody reflects the hard truth of human experience: “Against the strength of love,” Woody translates from the medieval Latin, “you will find no herb; against the strength of death no herb grows in the garden.”

The Fall of a Sparrow is propelled almost entirely by curiosity. It is infused with a sense of exploration and delight and, driven by Woody’s open-ended embrace of all life’s contradictory impulses, it illuminates subjects as diverse as sex, cooking, the nature of forgiveness, bats, terrorism and chaos theory—everything, in fact, except the elephant who paints abstract canvases in Philosophy Made Simple.

For Woody, literature makes “sense out of human life. He had great faith in books.” But it is clear from this book that he has even greater faith—if that’s the right word—in the richness of unmapped (but not unexamined) human experience. Nihil humani a me alienum, he declares, “Nothing human is alien to me.” And if you don’t like the bleakness of Cookie’s gravestone inscription, you can always choose the lyrics from one of the blues that Woody comes back to again and again. “Trouble in mind,” he sings, accompanying himself on a National Steel guitar, “I’m blue / But I won’t be blue always / Cause the sun gonna shine / In my back door some day.”