When NPR intern Emily White blogged in June about her largely unpaid-for music collection, she probably didn’t expect a nearly 4,000-word essay in response … or that musician and lecturer David Lowery’s challenge to her freeloading—make that free downloading—would go viral.

The brouhaha gained steam. Various industry and New York Times blogs took note, and eventually NPR’s Robin Hilton wrote a follow-up post. The unfolding discussion ranged from caustic criticism to high praise, but somehow one image saddened me most—White’s vision of a massive, shared online library, equally accessible by all willing to pay the subscription fees.

“How will people get to know her?” I wondered.

I was thinking of that moment when friends idle in your bedroom or living room and pass the time flipping through your music library. You don’t have to say a word for them to discover things about you that you might not think to mention—a taste for Sinatra or Robbie Williams, your favored method for organization, whether you are an expert or cursory fan of some band or musician. In fact, depending on where you house your object collections, guests don’t even have to closely inspect shelves to gain new insights about you with a mere glance at your living space.

We all use visual cues to size people up—whether they bike or drive, have an iPhone or flip phone, wear Toms or lipstick—yet with the increasing digitization of life, we have fewer objects to parse, fewer clues to friends’ and strangers’ mundane but sometimes defining secrets.

As a long-time mass-transit user, I almost get nostalgic now when someone pulls out a real book. Not that opening up a Stieg Larsson or Fifty Shades of Gray elucidates much, but often you get something solid: the student reading an anatomy text, a professional flipping a legal document, a flat-stomached woman closely reading a pregnancy guide. As I recently read Alain de Botton’s book Religion for Atheists on the train, I even got pulled into multiple conversations with strangers curious what the title meant.

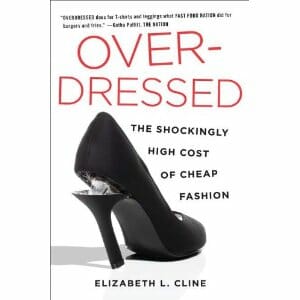

More and more, these details vanish inside our handheld devices, leaving us to draw largely from each other’s visual comportment and fashion choices. Particularly in densely packed cities, with cramped and costly living space, one’s wealth often goes into clothing. We find guides here not in the monothematic, late Steve Jobs, but in trendsetting celebrities whom photographers never catch wearing the same outfit twice. All this contributes to the rapidly increased pace of fashion trends that journalist Elizabeth L. Cline reports in her new book Overdressed, which explores the dark side of our addiction to cheap clothes.

Once, stores planned around a handful of major shopping seasons. Now some chains Cline describes as “fast fashion” outlets turn over their merchandise as quickly as every two weeks. And wherever they shop, Americans buy clothes with a mind-boggling frequency—on average, slightly more than one garment a week, Cline reports.

As you probably know, we can’t blame this on a bumper crop of new millionaires. Instead, as Cline shows, clothes’ new, incredibly cheap prices drive mass sales. And where people once valued clothing so much that Cline says it was “used as alternate currency in many societies,” prices have dropped to unprecedented lows in the past few decades.

Yet as per-garment prices plummet, they exact a substantial social, environmental and economic toll. In scarcely two decades, Cline says United States production of its citizens’ clothing shrunk from 50 percent to two percent. And despite its reputation as our fashion capital, New York today produces an almost negligible number of garments. Mind-bogglingly, Cline reports that this industry was the city’s largest employer just over a century ago, yet today New York’s Garment Industry Development Corporation, a non-profit, can hardly support its sole employee.

Nor is that man the only worker in the garment industry struggling to live on his income. As she travels to factories around the world, Cline finds that they rarely pay living wages … or limit work weeks to 40 hours. Even workers with better job conditions sometimes make less than peers in more unscrupulously run factories due to the work-week constraints, and Cline suspects that some of the sites she visited overseas, which feature some safety-related signs in English, are “more regulated showpiece factories shown to Western clients.”

Even the most ethical labor practices don’t address another problem Cline discovers: clothing fibers’ “unflattering environmental footprint.”

“Each fabric has its own complex and hefty ecological footprint,” she writes, yet one of the worst is also the most frequently used: polyester. Most of us know that fossil fuel isn’t unlimited and we should choose transportation and other goods accordingly, yet Cline reports that roughly one of every two garments we buy is now made from plastic-based polyester.

That doesn’t make these garments recyclable either. The easy-care blends Cline calls “Frankenfabrics” can’t be broken down into their constituent materials because “the technology does not exist.” Even what can be resold and reused through the thrift-store network comes to less than we might think.

In one of the book’s most fascinating chapters, Cline visits a Salvation Army warehouse in Brooklyn, which she learns must discard more than 36 tons of clothing every week. From there she follows the clothing bales to a bustling New Jersey textile recycler that processes “close to 17 million pounds of used clothing a year.” After workers carefully sort through the garments, the company sells any vintage finds to dealers, sends a large volume out for recycling into goods like industrial wiping rags and carpet padding, and then ships the rest to international second-hand markets, most in Africa. Even with this careful sorting, textile recyclers still dump about 5 percent of their intake into the landfill—more than 400 tons for the New Jersey outfit alone, just one of thousands of such companies around the country, according to Cline.

It’s about this point in the book that one can start to see a certain peculiar genius in Frank Zappa’s underwear quilt. The famously quirky musician commissioned the quilt to be made from female fans’ concert cast-offs after an early ‘80s tour. In some ways, Zappa proved very forward-thinking, even green. It’s that sort of creative garment repurposing that Cline encourages.

Throughout the book, the author uses her own journey with clothes to frame the narrative and soften the guilt-inducing blows of her research. By book’s end, she orders a sewing machine and starts altering clothes that don’t fit, restyling others and even repurposing some garments into bags and household linens.

For my part, Cline’s book and example inspired action. I actually went through my mending pile (where I found not one or two but six pairs of jeans needing patches). I’m considering a blanket or picnic sheet made from some other jeans I had planned to give the thrift store.

I’m also rethinking the way I talk about my clothes. I used to say that if a store’s sale fell short of at least 50 percent off, the merchants weren’t serious about my business. I would brag about such finds as the $100 suede boots I got for $10 at Urban Outfitters (though mostly because I couldn’t pass up such a discount—thankfully, I even ended up actually liking them). On the other hand, I once bought a pair of $500 Marc Jacobs shoes at a similar but slightly smaller discount, yet not even having the heel cut down could make my “bargain” walkable. After one or two miserable attempts to tread the streets of Manhattan in them, I consigned myself to foolish judgment and sold or gave away the heels.

In all this, I thought myself frugal, mostly shrewd and somewhat unique, unlike all the rubes and dupes paying full price. Yet Cline reports that video stories about shoppers’ clothing bargains—called shopping hauls—enjoy growing popularity on YouTube. She doesn’t discount our desire to feel connected to what we wear, but instead recommends a return to “old-fashioned habits.” We can alter and mend clothes and spend money only on garments we really love and that suit our figures and personalities, regardless of the trends.

The same day I finished reading Overdressed, I came home to a box I’d been eagerly awaiting. It held a pair of polka-dotted, high-heeled oxfords, part of a longstanding American brand’s partnership with a hip young New York designer. Online pictures caught my attention, but I’m picky about how much shoes taper, so I tried to find a local retailer. Unfortunately, the only shop sat on a hilly street in San Francisco. Since I only visit the city on work days, when I get around mainly by folding bike, I nixed that plan and decided to risk an Amazon buy.

At first the shoes seemed OK, but after wearing them a couple of hours, they turned out to offer little support…despite the touted “memory” foam, which sank into the probably plastic soles. When I thought about it, I realized I should have saved my money for shoes from John Fluevog or even Chie Mihara—brands that cost much more, but make thoughtfully constructed, unique shoes with comfort and long-term use in mind.

It’s a mindset switch that’s difficult for my inner cheapskate to swallow at times, but if I added up the mediocre…if not regrettable…$30 or even $100 shoe buys in my, uh, 49-pair collection, I could certainly afford one or two pairs of really great shoes.

Unfortunately, even if a local used clothing store would buy my cast-off shoes, they wouldn’t give more than $10 a pair, if that. And, as I now know, even my clothing donations could well end up in industrial rags, or the landfill. As Cline says, “Charities have become our dumps.” Unfortunately, I could stand to take a rather large load to the dump. After reading Cline’s confession that she owned at least 354 pieces of clothing, not including socks and underwear, I decided to tally my own collection. Surely I couldn’t own as much as that!

And it was true. If I leave out the two or three things I’m planning to substantially alter, and cross my fingers it’s possible to return the once-worn polka-dotted oxfords, I own 353 articles of clothing, outside scarves, socks and underwear.

Here I come back to Frank Zappa. If he could repurpose panties in a form that now adorns a Biloxi restaurant that I believe at least some families patronize, surely I can find something to do with the half-polyester “Barenaked Athletics” shirt and baggy linen pants I no longer wear.

Maybe I could cut some garments into strips and braid them into rugs, as the latest issue of Do It Yourself magazine suggests (albeit with different fibers). I might try making dishtowels out of the pants.

Such projects would not quickly winnow my clothing glut, but then Cline proposes a “slow fashion” cure for our cheap clothing habit. Slowing down means buying and doing less, but it also brings the freedom to invest more deeply and meaningfully.

I’m starting to think a T-shirt rug could be an awesome conversation piece.

Anna Broadway is a writer and Web editor living near San Francisco. The author of Sexless in the City: A Memoir of Reluctant Chastity, she regularly contributes to the Her.meneutics blog and the coffers of various yarn stores. Find her on Twitter @annabroadway