As the rockers of the ‘60s and ‘70s reflect on their lives—or feel low on disposable cash—many decide to produce memoirs. They return to their youth to describe formative musical experiences, moments before they wore impregnable rock star armor. They channel the unchecked excitement of younger, more innocent selves.

Often the same bits of music initiated profound experiences for different musicians. Graham Nash, for example, fell hard for Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” a song that also had a marked effect on Keith Richards, according to their respective memoirs. Nash traded his lunch for “a 78-RPM copy of ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula,’” literally going hungry for a precious recording. At a high school dance, he talked himself into going to flirt with a girl, only to be blindsided by a recording of the Everly Brothers’s “Bye Bye Love.” For a moment, he forgot everything, including the girl.

After his narration of this event, Nash writes, “[i]t was like the opening of a giant door in my soul, the striking of a chord, literally and figuratively.”

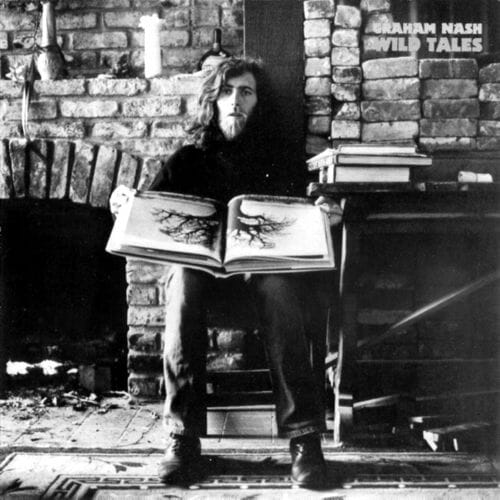

Sadly, this shatters the magic, and you’re left with Wild Tales, his off-putting memoir.

Is there any Englishman who wants to be American more than Graham Nash? Unlikely. I bet plenty of listeners who love Crosby, Stills, Nash and occasionally Young may not know that the N guy hails from across the Atlantic. After spending a good portion of the ‘60s cranking out hits in The Hollies—a British invasion group that specialized in sparkling guitar leads, a sturdy tempo and harmonies (they took a small detour into psychedelia, but who didn’t?)—Nash started hanging out in America. Soon, he went native, falling in with former Byrd David Crosby. Why Crosby? He “always had the best weed, the most beautiful women, and they were always naked.” (Italics belong to Nash.)

Even with the overabundance of rock books, the decade of the ‘60s never ceases to amaze. Wild Tales serves up historical documentation of two scenes: English pop and L.A./Laurel Canyon hippie-centric folk-rock. The Hollies played in competitions with every famous English rock band, and toured on double-bills with the Beatles. Nash had to write out the words to the Arthur Alexander song “Anna” for John Lennon to record the next day, since Lennon couldn’t remember them. Moving to L.A. and meeting Stephen Stills, Joni Mitchell or the Mamas and the Papas seemed only as difficult as getting on a plane and remaining sober enough to disembark on arrival.

In L.A., N connected with C and S, and the threesome recorded a dazzling self-titled debut album, released in 1969. It still sounds impeccable, blending three-part harmonies that one-upped (by a voice) Nash’s idols, the Everly Brothers. Crosby, Stills & Nash paired a loose, warm, front-porch feel with flashes of rock muscle. It’s impossible to dislike, and it set Nash up for life. He could have quit music right then and made bank performing for aging hippies until the end of time.

The rest, as those who can remember it say, is history. Neil Young appears, does a bunch of drugs, and disappears without warning…again and again. Nash raises a voice for peace and love and unity, whatever.

Unless, of course, you are a woman. Nash’s memoir comes off as so dismissive of his assorted partners of the opposite sex that it might have been written by one of the characters in This Is Spinal Tap.

He’s condescending towards the singer Marianne Faithful, whom he describes as “brilliant at image, pretty good voice.” (If you listen to Faithful’s comeback album, Broken English, you can hear her push back against a lifetime of comments like that.) He only talks to Mama Cass when he can’t find the girl he wants to flirt with. “Beautiful women are hard for me to resist,” writes Nash, like he’s discovered some rare secret. “Quite frankly, I could never keep it in my pants.”

This becomes unbearable once Nash starts his relationship with Joni Mitchell. He describes the way David Crosby, Joni’s previous lover, passed her off to him like chattel: “Croz…didn’t get hung up…He wasn’t territorial or…possessive…women were made to be loved every which way, and without any strings attached…he was going to make love to whomever he pleased, whenever he pleased…he knew I would be better for her than he was. And what happened was probably one of the most civilized…swaps that had ever taken place.”

What did Nash swap Crosby in exchange for Mitchell? A guitar? Maybe just some more of that good dope?

There’s a great moment when Mitchell calls Nash sexist, and the wheels start to turn slowly in his head: “Some kind of argument broke out, with Joan yelling that I hated all women. Coming from anyone else, I would have dismissed such an irrational remark, but from her I had to think about it…”

A moment of epiphany?

Nah. N dismisses the “irrational remark” as “nothing more than a way to strike out at me.”

The reader may cheer when Mitchell finally pours “a bowl of cornflakes and milk” on Nash’s head. (Too bad it wasn’t boiling grits?) Nash’s response? “I put Joni over my knee and I spanked her.”

Teach your children well…but teach them differently.

It may not be surprising that Nash the rock star would be sexist, but his absence of self-awareness poses another kind of problem—it makes for a flat read.

Nash likes to praise himself, calling his music “irresistible,” or noting that “we sounded fabulous.”

Me? I’m for #teamMitchell.

Elias Leight’s writing about books and music has appeared in Paste, The Atlantic and Popmatters. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and can be found at signothetimesblog.