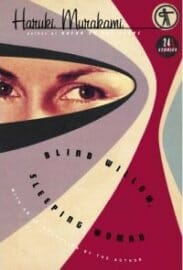

The Big Dream meets The Big Sleep: Popular Japanese writer brings Chandler pitch and precision to new work

I suggest you read Japan’s current literary superstar in the following way:

Sit down with Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman and a warm cup of something. Put a vintage jazz record on your turntable (remember those?). It might help if the record is one of the 40,000 in Murakami-san’s personal collection—once upon a time, the maestro owned Peter Cat, a jazz club in Tokyo. He takes his music seriously.

Now open this new collection of 25 short stories, Murakami’s 12th book. The title story, on its face, seems simple. We have a typical Murakami narrator: male, introspective, longing. He and his younger cousin are traveling to an ear doctor. As the two have been apart for years, conversation limps along with awkward pauses. The narrator’s memories rush in to ?ll the gaps.

He recalls a young female friend once sketching—straight from her imagination—an azalea-sized plant she calls a blind willow. It’s a botanical invention of her very own, a shrub one suspects germinated in the tangled shadows of Carl Jung’s side yard. The girl happily explains that the blind willow swarms with microscopic flies that burrow into human ears, where they lay eggs. These hatch, eat flesh and put victims to sleep. The Big Sleep.

Now, reading done, close your book… and go away. All day.

As you visit your own ear doctor (or more likely, Paste reader, as you ghost through vintage jazz-LP stores searching for records Murakami notes in these stories), the blind willow story will return, persistently, to thought.

That’s because the meanings in Murakami fiction are koi in a black pool. When it is time to be seen, up they rise, gold and gorgeous for one patient reader, cream and black and mysterious for the next.

In this sense of the written koan, Murakami is deeply Asian. But in literary terms, Murakami seems to be growing book after book into a wholly Western writer. Sales and notoriety shot up after 2005’s Kafka on the Shore. And why not? Murakami’s made from the DNA of Kafka, Gogol, Borges and Vonnegut. Like all these masters of metaphor, this writer slips through the silver membrane between life and dream as effortlessly as Alice through her looking-glass.

The most memorable stories of this collection stand at the two poles of Murakami’s talents. “Fire?y” is a love story, or a story of love that isn’t. This heartbreaker, played more or less straight, will grace anthologies, and it deserves the pages. “The Ice Man” is a love story, too—but of ruinous love. It’s told, like a folk tale, with preposterous, surreal cartoon strokes. The skill of the writer to make it work—to keep such a story sharp and memorable and terrible to behold—is an equal achievement.

Reading the whiskey-smooth sentences of Murakami is easier than reading Kafka in his leathery translations. But the Czech master might’ve personally popped out of a dream to deliver Murakami “A ‘Poor Aunt’ Story,” in which a man one day finds a “poor aunt” growing from his body. (“The Metamorphosis,” anyone?) Kafka, whom Murakami claims as a major influence, might also have gleefully invented the foreboding feathered judges in “The Rise and Fall of Sharpie Cakes.” In this parable, a man’s prize recipe must be evaluated by nightmarish murderous birds.

Look for spry old Vonnegut hopping around, too, most notably in “New York Mining Disaster,” where a world banally turns while very different events twist underground. And Vonnegut will chuckle over “The Year of Spaghetti,” in which a happily obsessive headcase treats himself to spaghetti—for 365 days. (Still, he doesn’t have to eat an old lady. That task is left to the hungry denizens of “Man-Eating Cats.”)

The obvious “pop” quality of Murakami’s work has always drawn ?re from Japanese traditionalists. It’s hard to say how much green-eyed jealousy lies at the heart of these attacks—Murakami is certainly a critical darling now. But who would envy the kind of reputation that’s at real risk with every inventive book? Here’s a style of writing addicted to over-the-top doses of daring and dash. When is it too much? When does artistry slip to contrivance? To be fair, Murakami’s Japanese characters are hip, modern, moneyed souls like those in Seattle, New York or Atlanta. Their stories bridge the Paci?c more readily in the year 2006 than traditional tales of, you know, samurai geishas with ninja lovers on sake binges with feudal wasabi sex toys.

Murakami is often mentioned in the same breath as Raymond Chandler. The author has, in fact, translated hard-boiled detective fiction into Japanese, an acknowledgement of literary debt, perhaps, and surely of respect. Remarkably, this new collection makes it hard to tell that Murakami doesn’t write in English—a tribute to his storytelling style and able translators. The transparency of the translation certainly boosts his attractiveness to Western readers.

And the Chandler in?uence stands out. The author of The Big Sleep wrote with acclaimed precision and an easy elegance that’s been the envy of a generation of followers. How odd that now a Japanese dreamer has stepped into the Ur-merican shoes of Chandler, writing the fantastic miniatures of this collection with the same effortless readability. The secret to Murakami’s success? He makes it look so easy. Hey, you say, anybody can write like this.

Dream on.