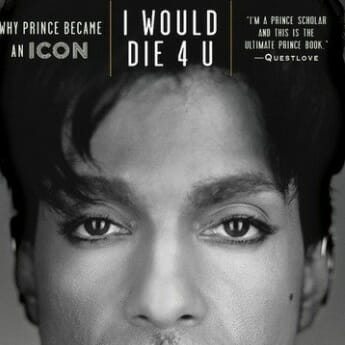

I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became An Icon by Toure

U Don’t Have 2 Be Cruel 2 Rule His World

Books Reviews

Can any book really do justice to the musician Prince? It’s doubtful. But an increasing number of authors have been giving it a try in recent years. At least three books about Prince came out in 2011, another in 2012, and 2013 brings I Would Die 4 U, an attempt by the music journalist Toure to explain what made Prince an icon.

Toure wrote frequently for Rolling Stone (also for the New York Times, Village Voice and other publications) in the ‘90s, often penning profile pieces where he got to play poker with the rapper Jay-Z or hole up with another rapper, 50 Cent, and his bodyguards. The writer created a memorable piece on Prince for Icon, describing a visit to the purple majesty’s mansion, where the two men played basketball together. (See Toure’s compilation, Never Drank The Kool-Aid.)

I Would Die 4 U—named after a compact, explosive little tune from Purple Rain— clocks in at an easy 150 pages, split into three sections. The first focuses on Prince’s childhood and family relationships and the way these affected his work ethic and his subsequent interactions with people. The second section examines sex in Prince’s life and music. The final explores the connections between Prince and God.

Toure sources from interviews—some new, many from other books about Prince or articles written about him in the ‘80s—and from musical experts. He relies most on the Roots’ drummer Questlove, a well-known Prince fan (the Roots recently served as the house band for a Prince tribute concert at Carnegie Hall).

The book goes in for macro-sized arguments, devoting a lot of attention to the demographic shifts Toure believes explain why Prince hit it so big. Prince, immensely talented, happened to arrive at the right place and the right time.

Toure sets the stage for this argument with an anecdote from early in the musician’s career, when the Rolling Stones invited Prince to open for them in L.A. As Prince’s longtime bandmate Matt Fink tells it, “‘A hardcore hippie crowd, they took one look at Prince and went what the heck is this. . . I’d say out of the first sixty rows of people, 80 percent of them were flipping the bird. And then they’re throwing whatever they could get their hands on.’”

(Prince tells it better—“‘I’m sure wearing underwear and a trench coat didn’t help matters but if you throw trash at anybody, it’s because you weren’t trained right at home.’”)

So if Prince had showed up earlier, Toure thinks “maybe he would’ve gotten that same cold response from other audiences.” But Prince arrived at the start of the ‘80s, allowing him to play into, feed off, embody, and most importantly, assuage, the fears and worries of Generation X (and piss off a few hippies at the same time).

For Toure, Gen X fears included: Anxiety stemming from widespread divorce among parents. The “specter of AIDS.” The “potential nuclear apocalypse of the long Cold War.” And “a nation of declining wages and shrinking job possibilities, where people worked harder for less money.” The author engages in some analysis of Prince’s lyrics, but Toure doesn’t try to deliver a book about how Prince put together albums or coaxed different sounds out of his synthesizers.

The initial section of I Would Die for U covers the classic artist-origin story, where troubled beginnings lead a boy or girl to channel energy into art as a means of escape. Prince had a strange family situation, marred by divorce and absent parents. In a 1981 interview, he said that he “ran away from home” and “changed address in Minneapolis thirty-two times.”

These troubles led him to become wildly driven, mistrustful of others, a great artist … but a forceful, unpredictable band leader and a hard man to love or work for. The musician Eric Leeds, who played horns for Prince, notes that when it comes to interactions with other people, “Prince is obsessed with always controlling the relationship entirely. . . Life to him is a movie in which a he’s the director, the producer, the screenwriter, the casting director, and he’s the star.”

His control extended to even the small details … like which clothes his musicians could wear when they left their hotel rooms on tour. Gayle Chapman, who played keyboards in an early iteration of Prince’s band, described the dress code: “If you walk out of your hotel room you were supposed to be in your rock-and-roll garb. Spandex. Naked. Hair. . . just to get razor blades at the hotel shop.”

The second section of the book will grab those who browse store shelves. Prince brought explicit sex to pop music in a way that no one else had (his songs make Marvin Gaye’s album Let’s Get It On feel like notes from a high school health class). Toure delves into sex in the ‘80s and reports on Prince’s own sex life. According to the author, “Someone who was intimate with him [Prince] and knows others who were, too, says Prince was not doing exactly as much screwing as he’d have you believe.”

Excuse me?

That’s not what I want to hear! Having exactly as much sex as his songs suggest (if not more) define part of Prince’s appeal—he’s doing all the crazy stuff that laymen and laywomen (puns intended) don’t get to do, can’t even imagine, or would cause themselves bodily injury by doing. Apparently, Prince, the man who wrote the song “Erotic City,” actually hung out in an “Erotic Small Town,” or maybe just an “Occasionally Erotic Apartment Building.”

(What was Prince doing with all that time when we assumed he was indulging his dirty mind? Toure informs us that “Prince loves to bathe women. And brush their hair. And sometimes he did these things in lieu of intercourse.” In fact, “‘One girl told me that she got frustrated because he’d rather bathe her.’”)

So the sexy part of the book isn’t very sexy. When discussing Prince’s song “Raspberry Beret,” Toure breaks things down for the reader: “She’s riding on his motorcycle, a phallic symbol, to the place owned by Mr. Johnson, synonym for a phallic symbol, and then going into a barn, which can be read as a yonic symbol; well, that’s a parade of sexual entendres.”

It is that.

The last section unpacks the religion in Prince’s songs. As Prince’s career progressed, he grew more explicitly religious; he officially became one of Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2001. It’s also worth pointing out that in the ‘90s and ‘00s, his songs weren’t as good. His career moves became more erratic, a la the famous renunciation of the name Prince in favor of an unpronounceable symbol. Questlove even offered Prince assistance in an article Toure wrote for Rolling Stone in 2000. The drummer referred to his work with D’Angelo on the album Voodoo as an “audition tape for Prince. . . I don’t know if it’s some bold-ass shit to say we know what he needs, but we wanna work with him.”

Toure explores some religious content of Prince’s lyrics, and talks to various experts about the connections between Prince’s music and explicitly religious music, like gospel. Toure also notes that the number seven “appears in the Bible more abundantly than any other number, just as it appears in Prince’s oeuvre more than any other number.” As a fan, I am perfectly willing to accept Prince’s canon as an alternate bible, but who’s counting?

Toure, in fact, pushes the religious connection too hard. He ends his book, “Prince knocked on America’s door through his music. . . flirted his way inside the door. . . when America’s guard was down, because we thought we were having a conversation about sex, Prince eased out his bible and said, let me also tell you about my Lord and savior, Jesus Christ.”

This reviewer isn’t converted by that assertion. Like many musicians, Prince often used religious imagery in his lyrics; as Toure acknowledges, singers who come from an R&B tradition have always equated religious and sexual ecstasy. There’s plenty of gospel influence in Prince’s tunes.

There’s also sex, love, fun, heartbreak, humor, tears, starfish, coffee, lusty ladies in hotel lobbies, Corvettes parked sideways, men who bathe with their pants on and women who wear only berets. Prince wrote songs at a prolific rate—in addition to putting his own albums out almost every year, he gave songs away to a number of other bands and singers, and many of his songs remain unreleased. The songs embodied extremes, relentlessly sexual and insatiable on the one hand, completely devoted and totally susceptible to heartbreak on the other. Hyper-masculine one moment, ultra-feminine the next (Prince occasionally used technology to speed up his vocals so he sounded more like a woman).

Prince irreverently mixed musical styles—here was a man capable of releasing the album Dirty Mind, a sub-30 minute ode to the pure pleasure of concise, immaculately constructed pop (and less concise, wild sex) … then just two years later, the album 1999. It cracked 70 minutes, endlessly working and reworking vamps and chord progressions, tweaking little explosions of melody and rhythm.

After Purple Rain, a No. 1 on the pop charts in 1984, Prince boldly spent his next two albums working through swirling psychedelia and string-heavy suites (with a French monologue or two thrown in for good measure).

And Prince wasn’t just a studio wizard. Onstage, he became one of the greatest—and most athletic—pop performers. In his 1987 Sign O’ The Times concert film, he executes an impossible series of jumps and splits while wearing orange high-heeled boots and matching bell-bottom overalls.

Prince once sang, “Life it ain’t real funky, unless it’s got that pop/ . . . everybody needs a thrill.” He provided the most exhilarating thrills and the poppiest pops.

Also, it seems likely, the best baths.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.