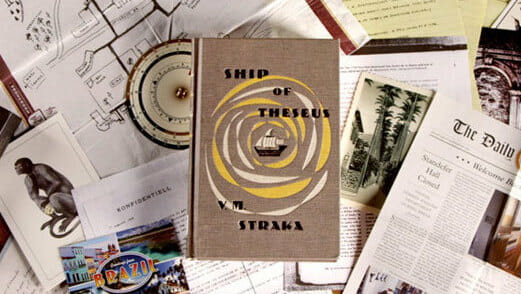

If you order a copy of S., you get a black cardboard case so handsomely designed that unsealing it feels like an act of vandalism. Inside the case awaits Ship of Theseus, which appears to be an old library copy of a book published in the 1940s.

Apparently written by the fictitious, mysterious V.M. Straka, Theseus is the field in which events of the story experience of S. will take place. This experience has been co-created by Doug Dorst, a novelist, and J.J. Abrams, one of the minds behind major film and TV franchises such as Lost, Cloverfield and the new Star Trek films. Though they share a credit, the brunt of the legwork appears to have been Dorst’s. He wrote novel and notes, while Abrams seems a sort of overseer/producer (as well as originator of the idea). A lot of effort went into something undeniably unique here, but this book unfortunately overstays its welcome. I’m glad I read it … I guess … but S. should have been so much better.

Taken on its own, Ship of Theseus weaves a curious and surreal mystery of a Kafkaesque amnesiac chasing a woman he may have loved in his previous life (I think). The protagonist passes through various locations while fighting agents of the evil industrialist Vevoda. Erratic footnotes pepper this text from the book’s equally enigmatic (and fictitious) translator, F.X. Caldiera, who may be V.M. Straka’s enemy, lover … or even the author him/herself.

But before we even get to the text of the novel itself, we plunge into the prime narrative of S., literally told in the margins. Two young Straka scholars, Eric and Jennifer, struggle to piece together the puzzle of the author’s identity via jottings that start on the endpaper and continue in a rainbow of inks throughout the book. The scholars end up using the pages of the novel as a giant instant messaging box, exchanging notes back and forth within the book. Their relationship deepens, and the novel becomes a scrapbook of their theories, pains and dreams. Together, Eric and Jen do the sort of noting that would drive many a librarian to heavy drug abuse: They highlight lines from the text. They draw arrows. They write extended passages that jump about from theories on the author’s identity to personal anecdotes. (God help the kind of reader who likes to compulsively make his or her own notes.)

As if all this weren’t enough, the book comes crammed with what old adventure games used to call feelies—extra little pieces of ephemera, like postcards, photographs and a compass code wheel, tucked between pages and just waiting to fall out and get misplaced somewhere.

I’ll give this to S.: It has the courage to be profoundly inconvenient. We have here a book 100 percent not designed to be read the way many of us probably consume books now—on public transit, on an electronic device or through headphones while we do other important things. Reading S. in public prompts questions from nosy strangers, not to mention a constant paranoia that some key note or postcard may have fallen out of the book as you put it back into your backpack or purse. Having gone through the entire thing only once, I admit I may easily have missed something important that might possibly change my opinion of the work.

But here’s that opinion as it stands: I found myself consistently impressed with the fictional literary universe the two authors created … but I rarely felt compelled to join in. At a certain point all of this world-building just exhausts.

For example, compare the way this book uses in-text codes with the memorable ending of poet John Hollander’s Reflections on Espionage. In that book, the reader must decipher an important final message that the book’s doomed spy protagonist cannot. In S., Caldeira’s notes are said to contain a secret message in each chapter that Jen and Eric usually figure out for us, but the results underwhelm. Reflections may be less sophisticated; it has a clearer sense of urgency and feels more dramatically satisfying. I find S.’s biggest enemy its own convolution, which starts out intriguing but eventually drowns one in tedious references to non-existent books, writers and conspiracies.

Worse, despite their passion and conviction (and the detail given to their handwriting), Eric and Jen make rather uninvolving characters. When they do finally declare their love for each other, it seems random rather than climactic because of the pacing of their notes. And when we learn Jen’s “dark secret,” it feels unmotivated by anything other than our authors’ need to give her one.

Ultimately, S. often feels condescending to the medium of print, like a eulogy for something still alive. The entire project hammers home the image of books as ancient, clunky, imperfect things. It seems especially ironic that this tome, intended by Abrams as a “celebration of the analog,” has actually pissed off librarians in the real world who find its price and extra pieces frustrating.

Many writers and readers have all been proclaiming “the death of print” for what feels like forever. It should be obvious by now that if print ever does die, it will be not with a bang but a whimper. If we can’t even get rid of vinyl records, why do people assume so much doom for the printed page?

S. suggests that print indeed will not drop dead, but instead continue on as a hipsterized accessory to the web, with printers that can simulate ink, coffee stains and even real human handwriting almost perfectly.

I guess that’s better than nothing.

W. A. Hughes is a writer and blogger based in Boston. His work has appeared in the Escapist, Paste and Topless Robot, and it probably doesn’t contain any cryptic secret messages, although you’re welcome to look for them.