Ground Zero Eros: A love affair blossoms from the rubble of 9/11’s chaotic aftermath

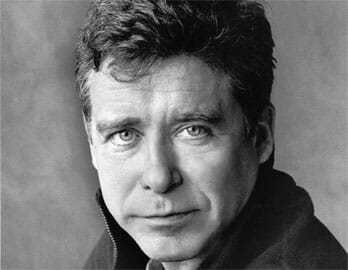

F. Scott Fitzgerald is his father. His uncles are John Cheever, Raymond Carver and Tom Wolfe. His siblings are Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz. His children include Jonathan Franzen, David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Safron Foer.

The members of this ill-fated literary family have enjoyed extravagant initial success followed by a dramatic tapering-off or critical backlash that threatened to do them in. As McInerney himself expressed in a recent Guardian article about fiction surrounding 9/11, “In America we tend to over-celebrate [precocious first novelists], and then we tend to kill them, figuratively speaking, in part because we expect so much from them after their brilliant beginnings.”

After the brilliant beginning of Bright Lights, Big City, which enshrined him 21 years ago as the spokesman of hip dissipated yuppies, McInerney struggled through his next five novels to live up to those expectations and keep his reputation alive. But he received so much critical backlash that he’d all but given up writing six years ago. Then, in the midst of his writer’s block and emotional ennui, some terrorists flew some airplanes into the World Trade Center towers, and his destiny changed course.

Like so many in Manhattan, McInerney roused himself from his apathy after that cataclysmic event. He volunteered to work for a couple of months feeding the national guardsmen and the rescue workers near Ground Zero, and he heard enough horrific stories and rumors to inspire him into a fresh beginning on a new novel which he called, sardonically, The Good Life.

The novel centers around the amiable Luke McGavock who—like McInerney—is in his 40s and comes from Franklin, Tenn., but has been converted for many years into a thoroughly smart, brash, wealthy New Yorker. He’s made so much money on Wall Street that he’s taken a sabbatical to re-examine his life and his marriage to a beautiful but flighty woman whose major talent is spending his money and attracting even richer suitors.

That fateful morning of September 11, he’d scheduled to meet his accountant at the World Trade Center but was delayed, only to find himself an ash-covered survivor. He happens across a lovely woman named Corrine Calloway, who’s destined to change his life. This is the same Corrine Calloway who was the heroine of Brightness Falls (McInerney’s best novel during his “drought”). She’s the wife of the literary editor Russell Calloway (remember “Nick Carroway” of Gatsby?)—a womanizer already separated from Corrine once and on the verge of doing it again.

Escaping their unfaithful spouses, Luke and Corrine volunteer together at a soup kitchen for rescue workers, just as McInerney had done, and gradually they fall in love. The Good Life, to whatever extent the title bucks irony, relates the sweet story of their romance—from start to finish—with many complications. They both realize how unsatisfying their marriages are, and they both recognize genuine soulmates in each other.

McInerney has always been recognized for the felicity of his prose, and for the most part The Good Life is his best-written novel, although there are passages tinctured with bodice-ripping purple. Kirkus Reviews has already declared the affair between Luke and Corrine an “overheated cliché,” where “the results read like a shotgun marriage between social anthropology and soap opera.”

But this isn’t quite fair to the author. Somewhere during his years of struggling to rise to others’ lofty expectations, McInerney had to choose between continuing to dazzle with original themes, mysteries and social statements, or simply telling a good story, and he wisely chose the latter. The Good Life will entertain, enthrall and touch the heartstrings, which is the most we can ask of any good novel.

It’s also one of the sexiest books of the season, containing gorgeous descriptions of kisses, plus numerous mentions (and two depictions) of far more intimate encounters. The Jayster, as his one-time friend Bret Easton Ellis calls him, gives the impression of never having made love without taking notes to be converted into graphic prose.

If conversation is McInerney’s strong suit, characterization has often been cited as his weakness, so it’s good to see how much we care about Luke and Corrine, and how much we want them to win. But McInerney, being a suave, cool New Yorker, can’t permit a happy ending, and that’s the one serious flaw in this otherwise charming novel.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, the oft-repeated refrain “So it goes” follows the death of anyone (or anything; the funniest line in the book is when it’s used for a beer gone flat). In The Good Life, the refrain is, “It is to die for,” or simply “It is to die,” the author’s common catch-phrase for something wonderful that, by allusion, also extends to the near-3,000 deaths of 9/11. Sardonic or not, The Good Life “is to die for,” an enjoyable read that may revive McInerney’s dusty standing.