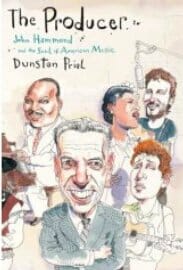

The man who discovered… everybody: John Hammond’s knack for finding talent made him a legend to everyone but John Q. Public

A good music producer remains invisible, working behind the scenes to allow artists to shine. Perhaps that’s why John Hammond, who produced an impressive roster of American musicians, never fully takes center stage in this thorough yet somewhat superficial biography.

Reporter Dunstan Prial has done a bang-up job of researching Hammond, and the very impulse to provide a biography of such a seminal figure in the music business—whose name is unknown to most laypeople—is to be applauded. Hammond possessed a knack for identifying great American musical talents, including Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin. At Hammond’s 1987 memorial service, one Hammond discovery, Bruce Springsteen, expressed his gratitude by performing a song by Bob Dylan, another Hammond discovery. Name a major American musician of the 20th century and Hammond pops up, Zelig-like, to play a role in his or her career. And Hammond was more than a mere talent scout: He also helped found the Newport Jazz Festival and he worked tirelessly for racial equality.

Prial recounts all this in smooth, readable prose that occasionally sings. (Eagle-eared Hammond “seemed to be perpetually standing at the door, waiting and listening for the knock.”) However, at times, Prial fails to get under Hammond’s skin and figure out what made his metronome tick. And it’s a pity because when the author, an Associated Press reporter, actually steps away from rote listing of Hammond’s achievements to consider not just the who, what, when and where, but the why of his subject, he inevitably touches on intriguing images and ideas.

Hammond was born in 1910, to an almost cartoonishly rich family (his mother was a Vanderbilt). They listened to classical music on a Victrola in their five-story house on Manhattan’s Upper East Side—equipped with its own squash court—and kept a box at the opera. Young John, however, preferred to hang out in the basement with the servants, who spun blues and jazz records. Prial theorizes cogently that these basement listening sessions ignited Hammond’s twin passions for civil rights and good original music, especially what at the time was known as “race” music.

Interesting, too, is Prial’s discussion of why Hammond never met with much success as an actual producer—despite this book’s promising title. For example, Hammond produced Aretha Franklin’s second record, Aretha, which was most notable for its lack of coherence, including everything from a cover of “Over the Rainbow” to the gospel song “Are You Sure?”

Prial notes, “Even Hammond’s detractors, those who for whatever reasons felt he got more credit then he deserved, have never seriously challenged his uncanny ability to spot raw talent. But the perception that he didn’t know what to do with that talent once he got in the studio was more widespread than he might have been aware. Indeed, several of his peers—some of them big admirers—thought as much.”

These are particularly high notes, but so long as Prial is following Hammond’s career, first as a journalist and then as a music-industry insider, he hits his marks solidly, if not always spectacularly. When he turns to Hammond’s personal life, however, his aim wavers.

I’m not a fan of histrionics and grasping connections in biography, but it’s plain stingy to gloss over the death of Hammond’s second child from a “serious infection” in a page and a half. Hammond, in the army at the time, didn’t leave his base for the hospital immediately, he claimed, because he didn’t receive a telegram alerting him to the boy’s condition, but his wife “somehow concluded that her husband had been attending a concert the day the telegram arrived and chose to remain at the concert rather than return home.”

That’s a huge bomb to drop and then scurry away from as quickly as Prial does. What kind of husband could Hammond have been that his wife would assume such a thing, even if it was incorrect? Prial doesn’t pause to ponder the possibilities; on the next page Hammond attends another performance (this one featuring trumpeter King Kolax), and the reader is quickly borne away from the tragic incident. (Hammond and his first wife later divorced.)

Prial had no lack of sources, including Hammond’s 1977 autobiography, John Hammond on Record. He also scored interviews with individuals who knew Hammond, but the results of these—or at least the quotes cited here—are strangely distant. Take Bruce Springsteen, who offers such lackluster insights about Hammond as, “He just exuded love of music” and “I think he was just instinctive, you know.”

As an interviewer, if Prial went for the jugular, he missed and caused a paper cut at most. You might say the same of his work as a biographer. The result never rivets the way it should, given the charisma and uniqueness of its subject.

Hammond sought music that would “hit him in the solar plexus” and “make the hair on the back of his neck stand up.” This biography rarely has that effect. In it, Hammond remains partially obscured.