Colombia, Violence and Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones

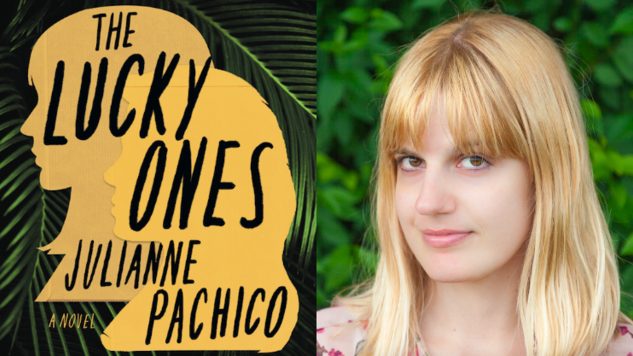

Author photo by Nick Bradley Books Features Julianne Pachico

Note: This piece is the Books Essential in Paste Quarterly #1, which you can purchase here, along with its accompanying vinyl Paste sampler.

In 1999, a history teacher friend of mine moved to Cali, Colombia, to teach at an elite international private school. On his first day, the school’s director handed him a roll of students. Then the director pointed to a group of names on the list and said, “Those kids get A’s.” Sensing the new teacher’s confusion, the director added, “Their families are very powerful.”

Besides adventurous teachers and government contractors, most Americans have little direct contact with Colombia’s wealthy elites or its decades-long civil war, which we regard as the non-domestic front of America’s 40-year War on Drugs. We recall Bill Clinton’s controversial Plan Colombia—which initiated mass fumigation of Colombian agriculture that reportedly hurt more peasant farms than coca plantations; reclassified Colombia’s Marxist peasant guerilla insurgency, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), as a narco-terrorist organization; and poured billions into supporting the lawless paramilitaries fighting the FARC, while doing little to slow the flow of cocaine into the U.S.

American linguist, historian and social critic Noam Chomsky describes Colombia as “a tragic country … plagued by extraordinary violence and terror.” More than a half-century of civil war has yielded 27,000 reported kidnappings, numerous extrajudicial assassinations, and a death count of 220,000—81 percent of whom are civilians. The murders happened so frequently, and with such wide dispersal around the country, that national newspaper El Tiempo began publishing a “Weekly Map of the War” to pinpoint all the places reporting violence each week.

At this writing, Colombia is undergoing a peace process fraught with failed plebiscites, vote-tampering, rampant misinformation, ongoing political assassinations, and tenuous progress signified by the incipient demobilization of the FARC. “To understand what is happening with the Colombian Peace Accords,” wrote Colombian activist and economist Héctor Mondragón in an early December 2016 op-ed, “it is necessary to identify the enormous political power held by Colombia’s large landowners. Without understanding the problem of the concentration of land ownership, it is impossible to understand anything that has happened in the country in the past eighty years.”

Indeed, Colombia is a country characterized as much by colossal disparities in personal wealth as by inescapable political violence. The war-ravaged nation includes both a massively dispossessed peasantry and an agribusiness elite whom decades of war have only made wealthier.

Are Colombia’s monumentally moneyed 0.1 percent the titular “Lucky Ones” of Julianne Pachico’s mesmerizing book? Yes and no. Set in both Colombia and New York against the backdrop of the civil war between 1993 and 2013, The Lucky Ones does concern itself with a handful of young women whose paths converged in a Cali private school in 1993. But as the war and the drug trade intrude on their lives (and those of their relatives, teachers, maids, and boyfriends), the question of what makes anyone lucky in such a dangerous world becomes almost impossible to answer.

Even more than it eschews such easy answers, The Lucky Ones steadfastly eschews ease. Despite Pachico’s luminous writing, the specter of terror, of kidnapping, of who will be taken next makes The Lucky Ones an unsettling read. Its perpetual perch on the edge of disaster—both real and surreal—leaves the reader in a state of dread reminiscent of Nathan Englander’s Argentinian desaparecido novel, The Ministry of Special Cases.

But the genius of The Lucky Ones is that Pachico creates a palpable anguish with a lighter touch than the gloom that hangs over Englander’s book. The Lucky Ones often feels playful, in part because it consists of interlocking short stories that have been shuffled out of sequence, requiring re-assembly to understand how they fit together. It almost seems like a book more easily understood backwards than forwards.

The Lucky Ones begins, appropriately enough, with a chapter called “Lucky.” It describes what appears to be a FARC abduction of a privileged teenage girl that sets the book on its ominous course, but it plays out like a coy seduction, more menacing in its unnerving inevitability than its action.

At the center of the book stands “The Tourists,” an acutely observed study of middle-aged social mores worthy of John Cheever. The story unfolds at a lavish party on a Cali aristocrat’s palatial finca, feeling Cheever-esque in everything except its location. But following a creepy perspective shift—from the party’s frustrated host to an unspecified “we”—Pachico reveals the observer is not alike Cheever’s empathetic, omniscient eye, but rather a band of FARC guerrillas lurking on the party’s fringes. They wait with kidnappers’ resolve for the most opportune moment to strike: “We’ll be watching. We don’t mind. We’re not in a hurry.”

A subsequent chapter captures the party’s aftermath from an angle that highlights an inspiringly askew imagination. “Junkie Rabbit,” a Colombian sequel to Watership Down, picks up the story a generation past the rabbits’ heroic migration, when the hard-earned new warren has degenerated into a crack den.

It’s obvious from these chapters that nothing is conventionally cohesive in The Lucky Ones, with its looping sense of time and fractured narrative structure. But there is an enduring sense of an ungovernable world unraveling, even as the disparate strands of this deeply affecting novel finally converge.

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.