Nickolas Butler Talks Family Secrets and the Rust Belt in The Hearts of Men

Books Features Nickolas Butler

At the very center of Nickolas Butler’s affecting new novel, The Hearts of Men, is a scene Butler drew in part from his own life.

Protagonist Jonathan Quick and his teenaged son Trevor, en route to a Boy Scout camp in rural Wisconsin, stop in a tiny town to have dinner with Jonathan’s boyhood friend Nelson Doughty, who also happens to be a scoutmaster and the camp’s director. Already several drinks along, Jonathan surveys the supper club “and finds the evening about as perfect as he could have hoped.” But the evening is anything but perfect for Trevor.

Jonathan has brought his mistress to dinner, a woman Trevor didn’t know existed. To justify his actions, Jonathan proceeds to enumerate his wife’s many failings to his son, explaining with drunken candor how the fun and sex have long since left their marriage. He concludes by dismissing his near-Eagle Scout son’s youthful notions about honor and love with a vivid doomsday prediction of how Trevor’s own girlfriend will cheat on him and break his heart. “So,” Trevor responds, “you thought you’d insult my relationship with Rachel, and admit that you’re not in love with Mom, all in the same night, and that wouldn’t break my heart?”

Much like the fictional Jonathan Quick, Butler’s own father once got drunk and sprang his mistress on his teenage son over dinner, albeit in a hotel restaurant in Chicago rather than a northern Wisconsin supper club. “For a long time I was very angry at him,” Butler recalls in an interview with Paste. “And then life just happens, and you get married and have children, and you just sort of let it go.”

Nearly two decades later, Butler was flying to Cincinnati to promote his first novel, Shotgun Lovesongs (2014), when he and his seat-mate struck up a conversation. “I tell him I’m a writer, and he asks what I’m working on,” Butler says. “I just start throwing out these ideas about my dad and that dinner, and the man gets very quiet. He goes from totally gregarious, having a ball, to saying nothing. And when I finish my story, he never really talks to me for the rest of the plane ride until he stands up and says, ‘I hope you can take it easy on your dad in the book.’”

Nearly two decades later, Butler was flying to Cincinnati to promote his first novel, Shotgun Lovesongs (2014), when he and his seat-mate struck up a conversation. “I tell him I’m a writer, and he asks what I’m working on,” Butler says. “I just start throwing out these ideas about my dad and that dinner, and the man gets very quiet. He goes from totally gregarious, having a ball, to saying nothing. And when I finish my story, he never really talks to me for the rest of the plane ride until he stands up and says, ‘I hope you can take it easy on your dad in the book.’”

If it’s a bit too simplistic to say that Butler “takes it easy” on his dad in The Hearts of Men—or to presume that Jonathan Quick is Butler’s father—the advice stuck: “I realized, the project of this book is not writing from the perspective of a heartbroken 16-year-old boy. The project of the book is trying to get inside the head of the dad and figure out what in hell is he thinking in this moment.”

“And it’s not just me and my dad,” he adds. “It’s crazy how, when I talk about this to other men my age, how many will say, ‘Yeah, my dad pulled something like that too.’”

The Hearts of Men, like Shotgun Lovesongs, digs deep into the landscape of northwestern Wisconsin where Butler grew up and still lives today. Shotgun Lovesongs’ most noteworthy cultural touchstone was Bon Iver’s LP For Emma, Forever Ago (2007)—an ethereal indie-folk masterpiece steeped in the bone-chilling isolation of endless Iron Range winters. For Emma was composed and recorded in a northern Wisconsin hunting cabin by Butler’s Eau Claire, Wisconsin high school classmate Justin Vernon—and it’s a story that partly inspired Shotgun Lovesongs.

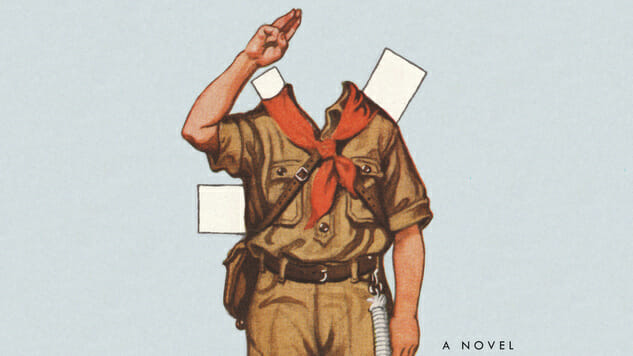

The Hearts of Men returns readers to northwestern Wisconsin but touches down in several eras, beginning at the Camp Chippewa Boy Scout camp in 1962 and concluding in the same camp 60 years later. Much of the novel follows campmates Jonathan and Nelson’s tenuous friendship and their struggles with honor, duty, relationships, violence and the lingering imprint of war over the decades that follow.

With its attention to Boy Scouts, baseball card-collecting and other “stuff not on the tip of people’s tongues right now in 2017,” Butler acknowledges the “measured sentimentality” found in The Hearts of Men. He recalls a quote from the late Michigan novelist Jim Harrison: “The novelist who refuses sentiment refuses the full spectrum of human behavior, and then he just dries up. I would rather give full vent to all human loves and disappointments, and take a chance on being corny, than die a smartass.” Likewise, Butler maintains, “You have to tackle love, you have to tackle disappointment, you have to tackle passion—all those things that create fiction with a pulse.”

Besides the incident with his father, Butler says The Hearts of Men was also inspired by his relatively late-in-life first reading of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. It’s easy to see the connection in the savagery that boys and men exhibit when loosed upon the Wisconsin woods at Camp Chippewa. Butler also suggests that The Hearts of Men, “responding in many ways to the Republican presidential primary race” (which, Butler argues, “had a lot in common with Lord of the Flies”), reflects darker times than Shotgun Lovesongs, written during the relative optimism of Barack Obama’s first term. “America had changed a lot,” Butler says, “and I’m not ever going to stay in the same foxhole and pretend like nothing’s changed.”

One thing that has changed for public figures identified with the American Midwest is the media’s preoccupation with the region in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election and the “Why did the Rust Belt turn red?” narrative that emerged in its wake. Although Butler has neither pursued nor been drawn into the sort of de facto “voice of a region” punditry granted to Hillbilly Elegy author J.D. Vance, he concedes, “I have done some interviews about my life here in rural Wisconsin and my take on the thing. But I really don’t know how I feel about that. I’ve been thankful, in a way, for any kind of media attention. On the other hand, let’s talk to some younger people who are going to be the face of this country. Let’s talk to some non-white-dude people.”

Butler also warns against painting, with too broad a brush, a region that he’s dedicated his career as a novelist so far to capturing—VFW halls, brutal winters, bonfires, paper mill smells, supper clubs and all. The Hearts of Men, like Shotgun Lovesongs, examines a Midwestern rural middle class whose contemporary lives aren’t necessarily defined by the ghosts of their region’s manufacturing past.

“Eau Claire is not the Rust Belt. And that’s an interesting storyline that I haven’t really seen people pick up,” Butler says. “The Uniroyal Tire plant closed in in the early ‘90s, when I was about 12. Eau Claire could have dried up and blown away. It almost did, but it didn’t, thanks in part to people like Justin Vernon, and local publisher Nick Meyer, who loved this place and just wouldn’t quit it. It might make more sense for them to live somewhere else, but that’s not what they were going to do. They were going to stay here and fight for it. And because of people like them, now we have an arts community, with some high-tech businesses that are starting up here because the young people that are part of those businesses want to be around a great music scene. So I feel like my story is not, ‘Oh jeez, let’s go look at our rusted-out factory and lament the ‘70s.’ We’re not dying here. That’s not my narrative.”

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.