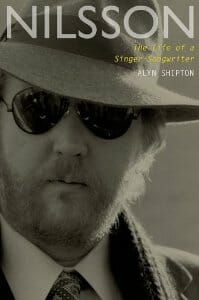

Nilsson: The Life Of A Singer-Songwriter by Alyn Shipton

He put the lime in the coconut

Books Reviews

Harry Nilsson’s story can be adjusted to fit any number of narratives. He’s the poor kid who made good but couldn’t handle success. The hard-working banker who wrote songs all night. The wacky artist. The Beatles fan who tried to drink his idols under the table. One of a crop of artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s who helped redefine the power of the studio in pop music. A symbol of the crazy excesses of the recording industry in the old days.

Alyn Shipton’s biography of Nilsson (the first) shows in meticulous detail the ways these stories come together to capture a man described both with superlatives—“finest white male singer on the planet”—and caveats— “nobody…is as much of a paradox.”

Biographies about musicians from the ‘60s and ‘70s can often be reduced to a sort of checklist:

Born? Brooklyn. Check.

Source of song? Shipton believes Nilsson suffered a “deep psychological wound” when his dad left. Mom wrote some songs, and she also liked booze and forging checks—Nilsson had to hold up a liquor store once to pay off a debtor (he did it with his hand in a pocket pretending it was a gun). So young Nilsson had music in his blood, plus an intense childhood for inspiration. Check.

Pop awakening? Listening to groups like the Coasters and Little Richard on the radio. Check.

Nilsson’s story, however, diverges from the familiar path of your rock and roller. He lands a job at a bank, not often a stomping ground for pop-smiths (though one notable poet, Wallace Stevens, spent much of his life working as an insurance man).

From this vantage point, Nilsson saw “two ways of breaking into the music business.” He could “pound the streets,” or he could get in tight with the bunch of studio musicians and songwriters responsible for the lion’s share of the pop coming out of Los Angeles. (For more information about this gang, read Kent Hartman’s The Wrecking-Crew: The Inside Story Of Rock And Roll’s Best Kept Secret.)

Nilsson first spent some time working the pavement. Then he switched gears and eventually met Phil Spector, whose girl group wall-of-sound was sweeping America around this time, and John Marascalo, who had written Little Richard’s “Rip It Up.” His songwriting rapidly improved—Nilsson’s “This Could Be The Night,” recorded by Spector with the Modern Folk Quartet, found a big admirer in the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, no slouch in the songwriting department himself. Nilsson now only needed the right connections.

Nilsson arrived with Pandemonium Shadow Show, in 1967. The album mixed his mom’s love of Tin Pan Alley and vaudeville, his own admiration for the Beatles and a knack for studio wizardry and big, brassy sounds that show Spector’s influence. Not imitation: Nilsson’s songs have a levity and swing completely unlike the thunderous battering of Spector’s work. “You Can’t Do That,” an homage to the Beatles, also served as a post-modern manifesto— Nilsson composed the song entirely from lines written by the Fab Four. And the Beatles famously dubbed Nilsson their favorite artist.

The albums Nilsson released between 1967 and 1972 represent his most exciting work. At the peak of his powers, with the best musicians that LA and London had to offer, and through a never-ending series of takes and retakes, dubs and overdubs, Nilsson expanded and improved his unique brand of pop pandemonium. He incorporated soul, blues, rock and doo-wop into his original mish-mash. He took his own composition, “Coconut,” an instantly memorable piece of childish nonsense—“she put the lime in the coconut, she drank ‘em both up”—and an excellent audition for ventriloquist school (Nilsson sings in a different voice for each of the songs’ three characters) to number eight on the pop charts.

Such vocal dexterity and pop instincts made Nilsson one of our great interpreters. Interestingly for a man who wrote so well, several of Nilsson’s best songs turned out to be covers. He recorded an entire album of Randy Newman’s songs, for example, and Fred Neil and Badfinger, respectively, wrote the two songs that won him Grammy awards, “Everybody’s Talkin’” and “Without You.” (Conversely, the definitive versions of some of the songs he recorded belong to others. Example: “One,” which Three Dog Night took all the way to No. 5 in 1969, “one is the loneliest number…”)

Nilsson doesn’t change the original version of “Everybody’s Talkin’” much, but he makes it more determined, a steady, rolling, irresistible march. While Fred Neil exclaimed from afar, Nilsson lay less distant, in the trenches with the rest of us, just trying to figure it all out.

Similarly, the original “Without You” takes too long, involves a lot of meaningless strumming, and doesn’t give the heartbroken sentiments—“I can’t live, if living is without you”—space to breathe, expand, explode. Nilsson opens things up with a sharp, spare piano arrangement, and moves from falsetto to full-throat on the chorus. He shortened his version by more than a minute, but packed it with enough grand anguish for a lifetime. “Without You” is one of the great piano-ballads of the ‘70s—a decade filled with plenty of them.

But success begets temptation. Nilsson proved to be no Keith Richards; as early as 1972, the partying impacted his work. He spent a lot of time furiously downing brandy with people like Bobby Keys, best known for his work with The Rolling Stones. (You know someone who drinks regularly with the Stones is more alcohol than man.) He ran with The Who’s notorious lush Keith Moon, and with John Lennon. Apparently during one weekend of acid, women and toe-sucking, the debauchery became so extreme that Nilsson had to tell Lennon “‘I can’t take any more pleasure.’”

On Nilsson’s 1974 album Pussy Cats (which Lennon produced), listeners can hear Nilsson’s degraded voice, the result of a throat destroyed by hard living. Although he continued to record until 1980, often with talented people in the studio (including Ringo Starr and the famous soul guitarist Steve Cropper), Nilsson’s most important contribution after his briefly glorious phase turned out to be political, not musical. He helped campaign for gun control after John Lennon’s murder in 1980.

Shipton’s bio goes into extensive detail, recording session by recording session, party by party, sometimes even whiskey by whiskey. We hear Nilsson’s recollections, as well as the memories of accomplices, lovers, ex-wives and partners in crime. For the readers who think one binge drinking event sounds much like another, the temptation to skim may be strong. (But don’t pass over the section on Lennon and Nilsson’s acid-pleasure overload.)

Chalk up another casualty to the rock and roll lifestyle. Some musicians, of course, thrive on the drugs and drama, but others get irreparably damaged. The system teaches them to scrap endlessly to get to the top, but not what to do when they get there. Why couldn’t Nilsson recognize his downward spiral, in the way that Lennon did, and pull himself out somehow? It’s no wonder he made “Everybody’s Talkin’” his own with such ease: “Everybody’s talking at me/ I don’t hear a word they’re saying/ Only the echoes of my mind.”

It didn’t take long before no one could hear Nilsson either.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.