New York Times editor picks at country music

Last June, as a guest of Marty Stuart, I got to sing a couple of my songs on stage at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. Being an old Welsh punk rocker with anarcho-syndicalist leanings and no hits on the country charts, I was flattered to be on the bill.

Porter Wagoner was there, all seven feet of him dazzling and bejeweled in sparkly white pajamas. So were Charley Pride, Neko Case, Connie Smith, Paul Burch—even that evil-looking little dude from hip-hop hat act Big & Rich.

That guy nearly ruined my night. There I was waiting in the wings for my big moment when he launched into the tale of his poor old daddy at home in his La-Z-boy all day watching terrible things on TV and wondering why if these people don’t love this country they just don’t leave it! The Ryman crowd roared in deafening approval—causing a gaggle of fluffy pink baby rabbits to attempt a breakout through my stomach lining. What the fuck am I doing here?

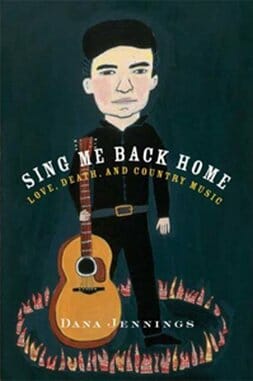

But it’s OK; Dana Jennings explains everything in this personal, hi-octane trek through country music’s golden age, from 1950 to 1970. Born and raised in rural New Hampshire, far from the gleaming towers of Nashvegas, he rejects the saccharin chauvinism, naked pandering and Republican fantasies of today’s country-music industry and lays claim to its classic vintage as a vital oral history that defines America’s white rural poor. Talking class to the myth of a classless society, he describes a world where the ’60s never really happened and the Great Depression dragged on forever. Framing hit songs about drinking, cheating, working and dying into the lives of his own dirt-poor family and run-down hometown, he reveals this music as more than just escapist entertainment: “a divine spark in your starved soul, a healing presence.”

Jennings takes a particular song, and then takes a little leap of his own. I love the way he hears Johnny Cash’s “I Walk The Line” as a cheating song, an alibi, a bare-faced lie. He creates a scenario around Webb Pierce’s “There Stands the Glass” in which Webb’s just back from fighting fascism, with wounds still red and raw, but his baby’s done gone and left him ’cause the only job he can get is in a stupid shoe shop.

He puts Jeannie C. Riley’s “Harper Valley PTA” in the context of Watts and Vietnam, and turns the spotlight on Loretta Lynn’s redneck feminism (“Don’t Come Home A-Drinking [With Loving On Your Mind]”) and Johnny Cash’s advocacy of Native Americans (“Ballad Of Ira Hayes”) and the incarcerated (“Folsom Prison Blues”) as a righteous antidote to country music’s burst of arch-conservatism.

Never shy to wax lyrical and poetic about the tunes that really matter to him, Jennings always brings it back home to the cheatin’ hearts, born-to-losers and hopped-up rounders he grew up with in Kingston, N.H. His own family’s dirt is dished in spades; Grammy Jennings was a trucker’s wife who at time got a little restless and, “like Will Rogers, never met a man she didn’t like,” while Uncle Lloyd managed to piss his whole fortune away. Jennings doesn’t even shy from the repulsive racism “of the Northern Variety” that led his Aunt Helen to vote for Southern segregationist George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election, and the less-than-charming way she described her sister keeping the cast-iron stove “shinier than a nigger’s eyeball.”

There is even an extended passage on the subject of outhouses, the sort of men who clean them out and the mortifying terror they can hold for the young and weak of heart. It forced me to remember the waist-high chickens that guarded the outside lav at my grandparents’ house in Croesyceiliog, South Wales, and the insane look in the birds’ eyes when I tried to bust through their cordon and reach the pot. My favorite song at the time was Tom Jones’ “Green Green Grass of Home,” and I would stand on a chair and sing that or “Delilah” at Christmas. Maybe I’m countrier than I thought!

Just before I got to do my bit at the Ryman that night, Charley Pride, the flip side of Elvis—a poor black boy who sounded kinda white—strode out onto the stage looking like he’d just spent the afternoon fishing leaves out of his pool.

The crowd gave up an even bigger roar, and suddenly I wasn’t scared anymore.

Jon Langford was a pioneer of punk music in The Mekons. He’s a painter, writer, producer and member of The Waco Brothers, an influential alt.country band from Chicago.