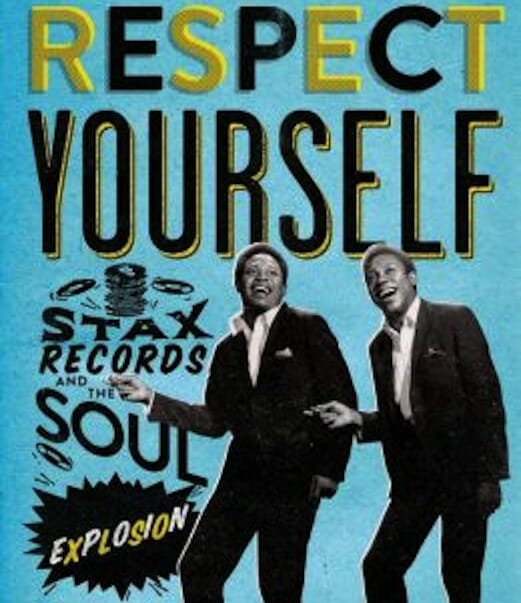

Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion by Robert Gordon

When The Well Runs Dry

Books Reviews Robert Gordon

Robert Gordon’s new book tells the history of Stax Records, the famous Memphis label responsible for some of Southern soul’s definitive recordings.

Stax began in a Memphis garage in 1957 as Satellite Records, a project of Jim Stewart, soon joined by his sister Estelle Axton, both white. From these humble beginnings, it enjoyed a fairy-tale rise, becoming a revered name, the home of the great Otis Redding, of “Soul Man” and “In the Midnight Hour.”

Gordon tracks this glorious ascent—and a vertiginous fall—as the label eventually collapsed under its own weight. He delivers a compelling tale with maximum effect, drawing on interviews with singers, musicians, songwriters, producers, secretaries, label heads—everyone he could get his hands on.

We know at least two other excellent histories of Stax. The noted chronicler of Southern music, Peter Guralnick, devotes a portion of his book Sweet Soul Music to the label, while also exploring the music of Muscle Shoals, Ala., and Macon, Ga. In addition, Rob Bowman’s Soulsville, U.S.A. devotes itself entirely to the history of Stax. (Bowman earned a Grammy for the liner notes he wrote to accompany The Complete Stax/Volt Soul Singles compilation.)

Gordon holds his own. He doesn’t appreciate Isaac Hayes’s album Black Moses, and he makes the occasional cheesy joke—“Dance? The horizontal dance”—but such minutiae don’t obscure the point. The story of Stax is undeniable.

In the beginning, you really loved me

After a couple of years in the garage, Jim and Estelle moved the operation to an old movie theater and renamed it Stax (Stewart/Axton). They set up a studio in back and a record shop in front. Jim initially felt lukewarm about R&B, but Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say” earned his loyalty.

Stewart and Axton established an open-door policy, and Memphis’s musicians seeped into the studio in talented, curious clumps. Rufus Thomas, a local performer and DJ, came by to give recording a shot. He brought his daughter, Carla Thomas. William Bell—who penned “You Don’t Miss Your Water”— sometimes sang backup for Carla. Booker T. Jones, a talented high school student, skipped class to play horns on a Rufus Thomas session. Al Jackson, an older, talented drummer who would play with two of soul’s greatest singers, Otis Redding and Al Green, knew Booker through club gigs, so he occasionally played at the studio.

Jackson provided an injection of punctuality and discipline, a firm rhythmic anchor for the high school kids—another group of whom busily bonded with Estelle Axton’s son Packy in the smoking room at Messick High School. This klatch included Steve Cropper, whose guitar playing would help define Stax recordings, drawing the admiration of famous musicians from the Beatles to Lou Reed.

Jackson taught Cropper to play his guitar like a drum, emphasizing the instrument’s rhythmic properties. Jackson also wanted him to pay attention to the beat.

“I never worked with anyone who thought keeping time was so important,” said Booker about Jackson. “He would hit you over the head with a drumstick if one eighth note or a sixteenth note was off.”

Stax’s first phase came to a close with national success. Carla Thomas landed “Gee Whiz” on the charts in 1961, and Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records swooped in, agreeing to handle distribution for 15 cents on the dollar. (Some of Carla’s releases also came out on Atlantic rather than Stax.) The same year, those high school smokers—now the Mar-Keys—recorded “Last Night,” which sold more than a million copies.

Here the cruel outside world butts an ugly head into Stax’s fairy tale. “First was the issue of authorship and its rewards…The money from a hit goes to the songwriters.” Just three people got their names on that record as writers. (Estelle sneaked on her son’s name.) No one cared too much at the time, but it foreshadowed future events.

I was too blind, I could not see

Stax ascended with dizzying speed. The addition of Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass cemented and settled the house band, now under the name Booker T. & the M.G.’s. The integrated group—hit-making long before the Family Stone or the Jimi Hendrix Experience—laid down a heavy groove, and they soon had a big song of their own with “Green Onions” (like “Last Night,” another instrumental number).

More people came to the record store—or tried their hands in the studio. A guitarist named Johnny Jenkins showed up, high on style, low on substance. (In fairy tales, not everyone turns out to be what he seems.) But Jenkins had this driver by the name of Otis Redding who kept insisting he could sing…

The MGs improved steadily. Isaac Hayes stepped in for Booker T when he took a break to attend Indiana University, and Hayes quickly learned how to write popular tunes, with the help of an insurance man named David Porter. Hayes and Porter connected with another duo by the name of Sam & Dave, collaborating on a series of bracing soul hits.

Enter promo-man extraordinaire, Al Bell, “six-feet-four bundle of joy, two hundred and twelve pounds of Miss Bell’s baby boy. Soft as medicated cotton and rich as double-X cream. The women’s pet, the men’s threat and the playboy’s pride and joy.” In addition to his business talent, Bell, as a black man, Gordon writes, “would enhance the administration’s credibility among the [mostly black] employees.”

“We weren’t a professional company before Al,” says Booker T. Jones. “We didn’t have big business going on. We had big music going on.”

They did have that. Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and Sam & Dave now consistently landed hits and all recorded classic albums.

Bell put the musicians on salary—it meant they didn’t have to work day jobs and play club gigs and do recording sessions to make a decent living. It also led, though, to “new proprietary concerns.” Suddenly, making music became a livelihood, not a fun outlet on the side. (Gordon terms this new responsibility and its new set of problems “weeds in the garden.”)

Stax started doing well enough to be choosy. The label decided not to work with Wilson Pickett after his album In the Midnight Hour. (He proved to be royal pain in the studio.) Stax passed on chances to play with Gladys Knight and Aretha Franklin. Bell even turned the music in a new direction, noting an increased price margin on albums. Stax only released eight albums in ’65 and 11 in ’66. That would begin to change.

You don’t miss your water till…

The end of 1967 and 1968 brought Stax’s third phase. In December of 1967, Otis Redding and several members of the Bar-Kays died tragically in a plane crash. It’s hard to imagine any label coming back from the loss of such an international star. Unfortunately for Stax, that disaster turned out to be just the beginning.

The year 1968 exploded, upheaval everywhere. A sniper shot and killed Martin Luther King in Memphis at a hotel Stax musicians and songwriters frequented. Riots took place across the country. About this time, Jim Stewart realized he had somehow managed to give Atlantic the rights to all Stax’s master recordings.

Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler claims that it all happened accidentally, that no one read the contract. “It turned out that there was a clause whereby we owned the masters,” a clause stuck “almost exactly halfway through the thirteen-page contract.”

“Atlantic,” writes Gordon, “owned everything that it distributed for Stax—even though it said ‘Stax’ on the label, even though Stax has paid all the money associated with those records and Atlantic had paid none and was at risk for not a single penny.”

Bottom line: Wexler, one of the shrewdest and cruelest men in the record business, had easily duped the inexperienced Jim. (Wexler insists in the book that he knew nothing about it and tried to give the masters back, but was prevented by the head of Warner.)

“It was corporate homicide—polite, sterile and deadly,” writes Gordon. To add insult to crippling injury, Sam & Dave jumped to Atlantic.

We find Stax’s last stage riddled with great music, violence and greed. The studio engineered the Soul Explosion, releasing 27 albums and even more singles in 1969 to make up for the loss of their masters. Al Bell looked actively to cross over from R&B to pop—he brought in Don Davis, who arranged strings for Motown. Isaac Hayes leapt from behind-the-scenes songwriter to massive solo star, releasing popular albums that influenced the course of R&B.

Big hits brought big money. Whatever remained of “the family illusion” at Stax, Gordon writes, “fell away, exposing a hierarchy of individuals, a business.”

The hierarchy forced out Estelle Axton, who once mortgaged her house for the label. Bell eventually bought out Jim Stewart in 1972.

Musicians and singers also began to spend extravagantly, attracting sharks on the prowl for a cut. The studio hired security; these men too often turned out to be sharks who simply switched sides. Hayes reveled in his new power—on one occasion, he had bodyguards beat one of his touring musicians nearly to death for ordering too much room service.

People began to carry guns—guns in a recording studio. They worried about being robbed for ostentatious displays of wealth, but also for more troubling reasons—after the assassination of Martin Luther King, the semblance of racial unity that existed at Stax, and in Memphis, faded.

“Resentment, hostility and fear were roiling among Memphis business elite…They [Stax management] were afraid someone would hide drugs in Stax, then try to bust them.” Al Bell felt that guns were “an American institution” used mainly “by the white majority” to maintain and consolidate power. He relates that he felt trapped, and forced to defend himself and his employees.

On top of these problems, new considerations suddenly influenced creative decisions. Bell told Gordon, “We’re talking about major Wall Street corporations and how their decisions and their thinking impacted with us and interfered, and in some instances, prohibited us” from producing certain music.

Key musicians, including Steve Cropper and Booker T. Jones, couldn’t take the situation. They left town for L.A. Meanwhile, the wildly ornate compositions of Hayes didn’t necessarily bode well for the studio’s old standby—tight, stripped down R&B.

Worst of all? No one could rein in the spending. Stax stayed friendly—maybe too friendly—with the loan guy at Union Planters National Bank. Money came easy. No one asked questions, they just kept asking for more. Stax grew to have the fifth-highest revenue of any black-owned business in the nation in 1973. Despite this, the company “didn’t have a real, structured management system,” writes Gordon.

Just two years later, deep in debt and out of hits, the whole thing imploded. The white-owned bank used Stax as a scapegoat for fraud charges. The predominantly black record company never had a chance. (Corporate homicide, part two.) Al Bell went to trial. Jurors eventually acquitted him on all charges.

The story of Stax captures the essence of the American dream. A tight-knit, talented group of working-class men and women, black and white, start out in a garage and go on to make national hits and earn screaming adulation on international tours. They work hard, they get better, they do something unique. They do it without the benefit of silver spoons or friends in high places. They get so big that the Beatles want to jam with Otis Redding and record Revolver at Stax.

Stax also captures the essence of the American nightmare, the one people don’t necessarily talk about. In a market economy, success leads to money, and money must be divided somehow. This creates winners and losers, haves and have-nots. Resentment shows up, sits down, festers.

Money-making has a way of perpetuating itself. It’s an addictive drug. It shifts priorities, so growth becomes the name of the game. People get left behind, or phased out in the name of consolidation. Then guns and violence make a cameo as America’s way of protecting earnings and ensuring loyalty when market-driven expansion tears apart ties of family and friendship.

That’s the thing about American fairy tales. All too often, they don’t have a happy ending.

Elias Leight’s writing about books and music has appeared in Paste, The Atlantic, Splice Today, and Popmatters. He comes from Northampton, Massachusetts, and can be found at signothetimesblog.