Can a coal-black avatar carry a boy to manhood?

Ah, rites of passage. Achieving manhood is so much easier now than it used to be. We parallel park. We put crosshairs on the side of a snorting 12-point. We kiss the girl.

Things haven’t always been so easy, boys. Masai youth of Africa venture out to slay a lion. Some cultures scar. Some circumcise. Baka Pygmies symbolically kill their children, and the ancient Greeks—well, sometimes their man-boy initiations were chaste.

New Hampshire-born Robert Olmstead writes of an especially hard coming-of-age experience in his sixth book. The rites of this work’s time and place—the backwater roads of Civil War Appalachia that all seemed to ?ow blood-red toward Gettysburg—make deep trivia of today’s manhood rituals. What, after all, is ?st-?ghting out behind the skating rink or drag-racing on the New Jersey turnpike, compared with holding up your wounded father’s head to brush maggots from a bullet hole?

Olmstead gives us a 14-year-old child named—get it?—Robey Childs. Robey’s mother has second sight, and one evening receives a premonition that requires her to dispatch her son from the mountain farm to fetch his dad home from the great Civil War. The premonition even comes with an inexplicable deadline—Robey must ?nd his dad before July.

Away then our hero travels, in a reversible jacket sewn by his mother—a garment blue on one side, gray on the other. The boy serendipitously acquires a superb horse from a friendly blacksmith, only to ?nd that such a steed is a possession most coveted. Robey loses the animal to a lousy (literally) wayfarer he näively trusts, and gets shot in the head for his trouble.

In time, he recovers, and horseless but wiser, lights out to ?nd his own private Barbaro—and his honor. As it happens in road novels, the boy falls in with odd wayward travelers, meets a girl, gets captured by Yankees, wins his horse and freedom back, loses his girl, and ?nds his way to his father, who’s lying on the famous Pennsylvania battle?eld on or about July 4, 1863. Robey has arrived too late.

That’s about it, actually. Now newly tough and sentient, Robey kills his ?rst man. He gets his girl back. He leaves home a boy and, through many toils and snares, comes home a grown man. Good story. The end.

If only.

Coal Black Horse is mostly memorable as an exquisite corpse, a ?ctive vision of war so vivid and gruesome that it remains in the memory—grotesque, stiff and gape-mouthed—after every other detail of Olmstead’s tale fades away.

Here’s an especially graphic paragraph—parental warning label here—describing the aftermath of Gettysburg:

Sticking among the rocks and against trunks of trees were hair, brains, entrails, and shreds of human ?esh cooking black in the heated air. There were men and horses swollen to twice their size, and in the days that followed he witnessed the shocking distension and protrusions of their eyeballs and he would eventually see them bursting open with the pressure of foul internal gases and vapors, their bloomings like horrible ?owers exploding their petals and leaves and spewing them across the ground.

There is a great deal of this kind of writing. In fact, such ghastly scenes dominate the book’s midsection, 60 or so of the novel’s scant 200 pages. I can honestly say that nothing I have read, in a willing career spent ?ipping the pages of war ?ction, ever left a more visceral (and I mean that word precisely) impression of the horror of war. The effect is staggering, saddening, a triumph of carnage-channeling.

To my mind, such an unsparing eyewitness report from atop the stone wall between Death and the green ?elds of life is the novel’s great strength. And, unfortunately, its great weakness. It is an unintended irony that Olmstead’s hellish descriptions of that great monster, war, render Robey Childs’ story, in the end, far less consequential. The war writing leaves nothing else to savor by the book’s end, no other vision—the horror of the battle?eld scenes overwhelms so completely, dominates so completely, that there’s simply nothing else one remembers of the book when the reading is done.

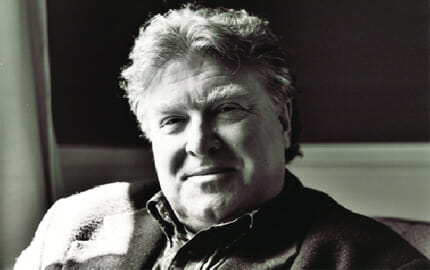

One other thing bears mentioning. Olmstead grew up on a dairy farm, the son of six generations who worked that land. The tough-minded, talented writer who sprouted there will grow weary, I’m afraid, of hearing about two other books that will inevitably be referenced in forthcoming reviews of Coal Black Horse.

The Red Badge of Courage and Cold Mountain are ?ne Civil War reading. Olmstead’s book ?ts nicely on a shelf just below them.

Not only teenagers, but modern American male writers come of age. And more and more, it appears, male ?ction requires a blood-rite. Guy writers who draw some of the keenest critical attention nowadays—Cormac McCarthy and Tom Franklin come to mind—seem happily willing to ink-jet fresh blood straight from printer to page. Masters of manners and drawing rooms seem out of business these strange times.

Where are the Cowards of yesteryear?

Gone to graveyards. Every one.