When I came back from the war in Vietnam I was 21 years old. In my platoon near the DMZ they called me the old man, but back in the U.S.A. I was just a not-very-introspective or self-aware kid, struggling to make sense of what I’d been through.

For the next few years, I had the classic symptoms of what used to be called “shell shock” or “battle fatigue”—a heightened startle reflex, graphic nightmares, dread paranoia, sudden sweats, hyper-vigilance—which is now known as post-traumatic stress disorder. Slowly, as I fit myself back into university life and the anti-war movement, the PTSD abated and something else took its place—an intense need to understand the effects of war on the human soul, my own included.

So I began to read, haunting bookstores and libraries to find the accounts of the men and women who had gone to war too. I collected and carefully immersed myself in more than 400 Vietnam War novels and memoirs. I made a quest of it, interviewing authors, going to academic conferences on the war, dedicating probably 20 years of my life trying to comprehend what I and many others had experienced. Books like Michael Herr’s Dispatches or Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried became my touchstones, because they combined exacting observation with high art and imagination, offering me ways to see inside and understand. Looking back, I realize that this powerful desire to know was my therapy, my way of coming to terms—from an adult perspective—with what I witnessed in my youth.

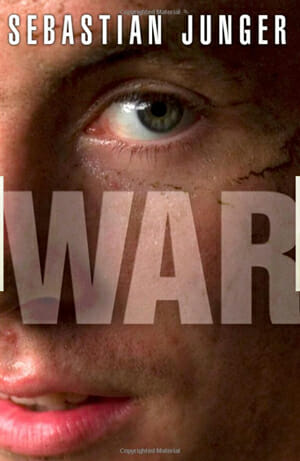

Sebastian Junger’s new book WAR, like most combat memoirs, attempts to short-circuit that process. In five trips to eastern Afghanistan’s combat-intensive Korengal Valley for Vanity Fair, Junger covered 15 months in the life of one platoon of Americans: 30 young men living and dying through their generation’s violent rite of passage. Fighting the Taliban and the jihadist foreign soldiers, the platoon from Battle Company went through what all combat soldiers do—they strip life down to its survival-based core, trying to kill the other guy before he kills them.

Unfortunately, the conclusions Junger draws from his courageous sojourn in Afghanistan don’t cut new literary trail. In the book’s three sections—Fear, Killing and Love—he reports that combat is an incredible adrenalin rush (“war is life multiplied by some number that no one has ever heard of”); that combat bonds men together like nothing else (“The defense of the tribe is an insanely compelling idea, and once you’ve been exposed to it, there’s almost nothing else you’d rather do.”); and finally, that war ruins soldiers’ civilian life (“…he’s crawling out of his skin because there hasn’t been a good firefight in a week. How do you bring a guy like that back into the world?”).

Junger spends most of WAR glorifying camaraderie, describing in detail entire battles or the massive killing power of American weaponry, and citing studies on fear and courage to bolster his sympathetic views of the grunts he profiles. His Perfect Storm, tough-guys-in-extremist style works well as straight reportage, but it pales in comparison to the truly transcendent insights of Dispatches or the deep, harrowing lessons of The Things They Carried. All great war books are also anti-war books, but this one misses that mark.

Here’s the problem: Journalistic detachment, and the profound, objective insights it can potentially produce, is a recent casualty of the military’s PR policy of “embedding” journalists. “I was an ‘embedded’ reporter,” Junger writes, “and entirely dependent on the U.S. military for food, shelter, security and transportation.”

The military has this one figured out: By placing journalists with the troops, and making them entirely reliant on those troops for everything (their lives included), the resulting coverage is bound to be essentially sympathetic.

That subjective, sure-fire sympathy produces accounts like this one—essentially one-sided, one-dimensional storytelling that presents and reinforces the perspective of one military, one nation. The best journalists who have covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have understood this not-so-subtle military propaganda tool, and have refused to be embedded as a result. If Junger had followed their example—or embedded himself with the Taliban, too—then we’d have a story.