You can stop any time

Some might say addiction is a disease of perception. For example, my dad drank every single day: He arrived at his local tavern to belt beers daily with more punctuality than he ever put into any job he had, yet the fact that he was an alcoholic escaped my perception until nine years after he’d suddenly died of heart failure at 52, when my sister gave me a book about adult children of alcoholics and about how, you know, we sometimes can deny the obvious and stuff.

“Oh, duh,” I remember thinking when the perception finally dawned on me.

I wonder, though, if it ever dawned on my dad. At the time he was alive it didn’t occur to either of us to classify him as addicted to alcohol. Granted, I was really young and the only knowledge I had of alcoholism was an after-school special in which a girl couldn’t bring her friends home to play at her house because her mother had a habit of sleeping on the living room floor. My father didn’t have a habit of doing that, he only did it sometimes.

See? Perception.

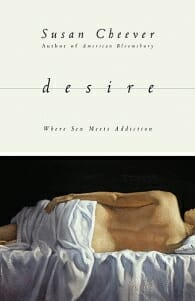

Susan Cheever talks a lot about perception and addiction in this book, which was an enlightening read although I think she should have titled it something else, because it seemed to me the book was more about addiction in general—with a heavy emphasis on alcohol addiction—than it was about sex addiction in particular. Cheever is, after all, the biographer of Bill Wilson, the co-founder of A.A., and she also authored the best-selling memoir Home Before Dark, in which she depicts life as the daughter of acclaimed author and recovered alcoholic John Cheever.

With Desire, Cheever combined her talents and created an amalgam between an informative reference and a memoir, using her own experience with her third husband as her primary case study. As a memoir-writing instructor, I’m always excited when I see a new rendition of this genre, because truthfully I don’t think I would have found the prospect of reading a staid, clinical study of sex addiction any more appealing than I would have found the act of actually having staid, clinical sex. But since the writer went to the trouble of baring her soul in all its squalid sex-addicted detail I figured, well, maybe I’ll learn something useful, like how to incorporate hanging harnesses into my home décor.

But here is where it gets foggy for me. Because I would have thought that a sex addict’s behavior would have been a lot more sordid than what Cheever is letting on in this book. Not that I was hoping for a litany of back-alley cluster ruts and other waves of shameful activity depicted in all their seamy detail, but Cheever’s own tale of sexual obsession was downright demure, it seemed to me. In short, her behavior simply did not seem so over-the-top to me that I would perceive it as addiction.

My perception of a sex addict is someone who practically has to wake up encrusted in a dried cocoon of strange DNA every morning—it doesn’t make the cut for me if it’s just a couple of one-night stands and one roller-coaster soul mate. But then that’s me. I’m not like Cheever in that I am experienced in studying bad sexual behavior; I’m only like Cheever in that I’m experienced in behaving bad sexually.

But I don’t think that makes me a sex addict any more than it makes every single horny coed on my dorm floor a sex addict. I’m talking about the past here, when I was younger and experimental and undaunted by the responsibility of being a good role model for my offspring. And even then I didn’t perceive it as bad behavior, really. I just perceived it as, well…fun.

I didn’t make a habit of sleeping around, see, I only did it sometimes.